|

Flowers and Fruits, part 4: Pollination

For

a flowering plant to

become a fruiting plant, pollen must be transfered from a stamen

(preferably on another flower, on another plant), through a process

called pollination. Next,

a sperm cell from inside the lucky pollen grain must penetrate

an egg cell deep within in the pistil, thereby performing fertilization

of the egg. The resulting zygote (fertilzed

egg) will develop into an embryo plant --a seed.

Depending upon the plant species, facilitated by adaptive

modifications to encourage a particular type of pollination

vector, pollination is most often carried out by some type of

animal, such as a bee, a bird, a bat or

a butterfly. Or a moth. Of course, many plants are wind-pollinated

(including grasses, sedges, rushes, and many trees) and a very

few

(eel-grass, for instance) are water-pollinated.

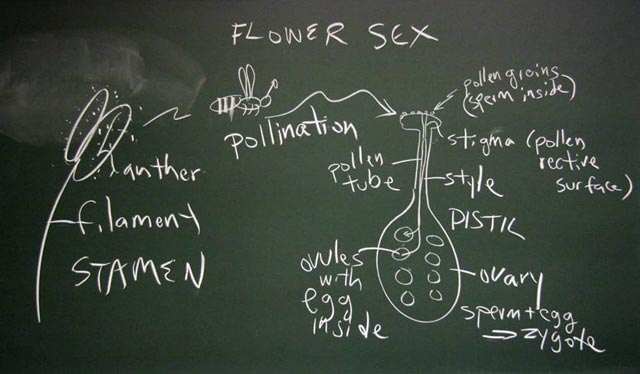

Below, an elegant illustration of the process. The stigma is a very

special environment for a pollen grain, having the proper nutrients and

growth-stimulating chemicals to enable the grain to grow a long, hollow

hair-like extenstion called a pollen tube down

through the tissues of the style, eventually bursting into a

egg-containing ovule located inside the ovary

at the base of the pistil. Each pollen grain contains only two sperm.

In a special angiosperm-only phenomenon called "double fertilization,"

one of the sperm cells fuses with the egg while the

pathetically

unlucky other one fuses with two other cells in the

ovule,

giving rise to a nutritive tissue called "endosperm."

Endosperm is food

for the developing embryo or a newly-sprouted seed. Popcorn

is mainly puffed endosperm. Yum.

Blackboard sketch of "flower sex."

Below, common rose-mallow. This robust marsh perennial herb is

pollinated by two types of large bees. One of them is bumblebee,

generalists that visit a great variety of flowers. The other is a

specialist hibiscus bee, Ptilothrix bombiformis

(Anthophoridae). The hibiscus bee assiduously gathers copious amounts

of pollen with which to provision her below-gound nest.

Hibiscus bee gathering rose-mallow pollen.

Below, a hibiscus bee

gathers pollen from a rose-mallow

blossom. Notice her first at another flower in

the background and that upon her arrival to the new flower, she touches the stigmas inconveniently placed in her flight path.

Hibiscus bee

pollinating rose-mallow blossom.

After pollination and

fertilization have occurred, some

or all of the

other parts --calyx, corolla, androecium and the stigma/style portions

of the pistil --may be shed. Within the ovary the ovule(s), each

contain a developing embryo. As they develop, the ovary

too ripens, sometimes assuming a fleshy form to elicit

consumption

by seed-dispersing animals. Thus a fruit is

a ripened ovary containing seeds.

Below, a rose-mallow fruit. It has opened (dehisced) to reveal the 5

section (carpels) of which it is composed and approx. 80 seeds. The

remnants of the calyx (sepals) are present but the other flower parts

are long gone. This type of fruit --a dry one, usually multi-seeded,

composed of 2 or more units (carpels) is a capsule.

The rose-mallow fruit

is a 5-chambered capsule.

Most pollination by animals is some type of mutualism in which both

parthers benefit. The pollinator gets food

--pollen and/or nectar -- and the plant receives a FED-EX-like

(UPS...United Pollen Service?) pickup and delivery service for pollen

grains.

If plants didn't pay for sex, there'd be no such thing as hummingbirds!

Usually, the plant - pollinator relationship is fairly flexible in that a

given pollinator can forage on a number of different plant species,

and a plant may have several different types of pollinators. An

exception to this pattern is the interesting and famous

exceptionally strict mutualism: the yucca - yucca moth

mutualism. The plant is pollinated only by one type (several

related species) of moth, while the moth is absolutely reliant on the

yucca plant to sustain its young.

Below, yucca. This is a eastern North American species that has been

introduced into our area, where it is frequently seen along railroad

tracks.

Yucca plants are

frequent along RR tracks.

Below, yucca flowers at

night late in June. The flowers don't produce nectar. Small anthers are

perched at the tip of filaments that are stout --well suited for a moth to grasp

on to. Small white moths flutter about, eventually settling inside

the bloosoms.

Yucca flowers and

yucca moths.

Below, a yucca moth gathering pollen. The moth's mouth

parts are specialized for both gathering pollen and storing it in a

ball under her chin. (Does a moth have a chin?) Soon afterwards, she

flies off to another flower on another plant.

Yucca moth gathers

pollen from anther of yucca flower.

Below, oviposition.

Arriving at a new blossom, the moth performs oviposition (egg-laying)

by piercing the flower's ovary with the tip of her abdomen and

injecting several eggs into the ovary. The larvae that hatch from the

eggs will consume a portion of whatever seeds are developing inside the ovary.

But this is only an effective strategy if indeed seeds are developing inside, so

her next step is pollination of that flower.

Yucca moth ovipositing.

Below, pollination.

After placing her precious eggs that are about to hatch into

an ovary, the moth would like to be more of a moth...she wants to be

mother. Hmm. To ensure that, the first act following oviposition is to

insert the ball of pollen previously gathered from another flower into

the specially shaped stigma, thus ensuring that her babies will have a

nice place in which to spend their childhood. She is a pistil-packing momma!

A pistil-packing momma!

Below, yucca fruits.

The moth's babies (larvae) consume some, but not all of the plant's

babies (seeds). Evebtually, late-stage larvae chew their way out of the ovary and burrow

underground where to pupate (form a cocoon) and over-winter.

Yucca fruits in late

autumn.

Back: Flowers&Fruits Menu

Next: Pistil Variation

|