|

|

Welcome

to bobklips.com, the website of Bob Klips, a plant enthusiast living in

Columbus, Ohio. Hedge (Osage-orange, Maclura pomifera) Delaware, Ohio. September 26, 2008 Osage-orange (Maclura

pomifera,

family Moraceae) is a medium-sized tree that is distinctive now because

of its softball-sized multiple fruits that adorn the branches and then

fall to the ground. The Moraceae is the mulberry family and, like

mulberries, the huge Osage-oranges are actually clusters of many small

fruits tightly packed together, derived from a head-like

cluster

of small individual flowers.

Osage-orange along road in Delaware, Ohio, September 26, 2008. Osage-oranges have been

the subject of

some speculation with respect to their palatibility to wildlife. Fleshy

edible fruits are an adaptation that serves to disperse

their seeds. There are few instances of wild animals eating

Osage-oranges, at least around here, and they seem to just sit on the

ground wondering why nobody likes them, and

eventually decay.

Osage-oranges on the ground, Delaware, Ohio, September 26, 2008. The apparent lack of

animal dispersers has lead some people to suggest that Maclura

pomiferais

an "anachronistic plant," i.e., one having an

evolutionarily co-adaptive connection with one or

more

animals that are now extinct. As recently as

10,000 years ago, there were numerous large animals ("megafauna"), such

as mastodons, mammoths, horses, and many others that are no longer with

us. Perhaps they liked these big green mulberries. On the other hand

there are a few observations in the remarkably small home range of the

species --tiny portions of Texas, Oklahoma and Arkansas (home

of the Osage Indians) --of squirrels eating them, and horses

avoiding them.

Osage-orange range map. (Peterson Eastern Trees Field Guide) While the natural range

of Osage-orange is

quite small, it is widepread in the midwest because it was once widely

planted as a living fence. Another common name is "hedge."

Osage-orange hedgerows have the

properties of barbed wire owing to its sharp stout thorns.

Osage-orange twig, showing a stout sharp thorn. The Fruits of Fall September, 2008 A

flower's ovary is the lowermost portion of its pistil (also

called the gynoecium), the female part of the flower. The ovary

contains one or more ovules, within each of which there is an egg.

After a pollen grain delivers a sperm cell to fuse with the egg, a new

embryo (baby plant) develops within the ovule, which eventually becomes

a seed. A fruit is a ripened ovary

containing seeds.

This month, many plants are in fruit that were more conspicuous earlier, when they were in flower. They are still beautiful and intriguing while in fruit, but they are certainly less attractive, because the portion of the flowers that served to advertise their presence to pollinating insects --the petals --have long since fallen off. Here are several fruits of September, along with pictures (MOUSEOVER to see) showing what they looked like earlier in the season. (The flower pics may have been taken at a different location.)  Great lobelia (Lobelia syphilitica) fruits. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, OH. September 17, 2008. Sullivant's

milkweed (Asclepias sullivantii) fruits.

Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, Marion County, Ohio, September 2, 2008. Jumpseed

(Tovara virginiana) fruits.

Nashville, Miami County, Ohio, September 20, 2008. Horseweed

(Solanum caroliniense) fruits.

Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, OH. September 17, 2008 The

Asters

of Autumn

September 19-20, 2008 Hocking County and Miami County, Ohio. The plant family Asteraceae (aster family) also has a traditional, more descriptive name: the "composite" family. This is because what looks like one big showy flower is actually a tightly packed cluster --a composite --of many small individual blooms. These flowers are sometimes of 2 different types: (1) centrally located, radially symmetric disk flowers, and (2) peripheral strap-shaped ray flowers. In the picture below, the honeybee is gathering nectar from the disk flowers while the spotted cucumber beetle is standing on a ray flower.  Flower head of a sunflower, Helianthus maximilianii. September 20, 2008, Tipp City, Miami County, Ohio. Below, a picture taken in 2007 shows individual flowers teased from a sunflower head to demonstrate the two types of flowers and show the individual parts (in some instances highly modified) that comprise a flower. Unless they are the only type present, the strap-shaped RAY FLOWERS are usually sterile, serving solely to attract pollinators as do the individual petals of a single flower, which they indeed resemble. The central DISK FLOWERS have their OVARY way down at the bottom of the flower (this is an "inferior ovary"). The ovary is the part that eventually develops into a dry one-seeded fruit --an achene --that is often colloquially referred to as a "seed." (A "sunflower seed" is a actually a fruit that you split open to eat the seed inside.) Just above the ovary are the SEPALS, so highly modified they have a special name: the PAPPUS. In the sunflower the pappus is a simple pair of scale-like bristles, but in other members of the Asteraceae such as the dandelion, the pappus is an eleborate parachute-like organ that aids in fruit dispersal. The corolla consists of 5 fused PETALS from which protrude the uppermost sexual parts of the flower: (1) the pollen-producing STAMENS which are fused into a tube through which grows the STYLE which is capped by rabbit-ear-like STIGMAS that receive pollen. Interestingly, the stamens split open and release theirn pollen towards the inside of the stamen-tube and so the pollen is presented on the non-receptive backsides of the stigmas. It looks like self-pollination, but it isn't. These flower parts are labelled in the alternate (mouseover) view of the picture below. MOUSEOVER the IMAGE to see parts labelled.

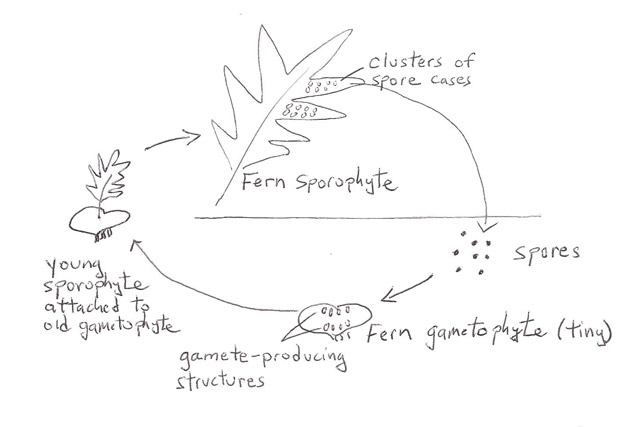

Flowers of Jerusalem artichoke (Helianthus tuberosus). The Asteraceae is the largest plant family in our region. It is not economically important; sunflower seeds, lettuce, artichokes, and safflower for oil are pretty much the only foods we get from the family. But aster family members are ecologically important. This family predominates, along with grasses and legumes, in prairies and meadows. It is especially conspicuous in late summer and autumn, when many of them are in flower, sometimes profusely. The most conspicuous members of the Asteraceae in our region at this time of the year are goldenrods (genus Solidago). These showy guys often get unfairly blamed for allergies actually brought on by ragweeds flowering at the same time as the goldenrods but which, being wind-pollinated, lack showy parts and so aren't noticed. Here are are two goldenrod species common in fields.  Canada goldenrod (Solidago canadensis). September 19, 2008, Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio.  Gray goldenrod (Solidago nemoralis). September 19, 2008, Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio. Vittaria appalachiana (family Vittariaceae) Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio September 19, 2008 Introduction: the typical fern life cycle. (Christmas fern example) The

plant life cycle is

more intricate

than the animal life cycle. It is an "alternation of generations" life

cycle in which one type of plant --the sporophyte stage of the life

cycle-- produces and releases spores. A spore is a cell

that develops independently into a new multicellular plant.

The

plant that develops from a spore is a very different than the

plant that

produced the spore. The spore develops into the

gametophyte

stage of the life cycle. A gametophyte is a plant that produces

gamete, i.e., eggs and sperm. Gametes (eggs and sperm) are cells that

must fuse together to advance the life cycle. When an egg is

fertilized by a sperm, the embryo that results develops into a

new

sporophyte. Thus, the plant life cycle alternates between a

spore-producing sporophyte and a gamete-producing gametophyte.

Here's a rough sketch of the fern life cycle, showing a big leafy sporophyte producing spores that develop into the miniscule inconspicuous gametophyte, which produces the gametes that give rise to big leafy sporophytes, and so on....(it's a cycle):  Sketch of fern life cycle. In the fern life cycle, the conspicuous and ecologically important stage of the life cycle that you would normally refer to as the "fern," is the sporophyte. Here's an example of a a typical fern sporophyte: Polystichum acrostichoides (Christmas fern).  Christmas fern showing fertile (spore-producing) leaflets at upper portion of plant. May 7, 2006, Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio. As

is often the case,

Christmas fern

spores are borne in pinhead-sized sporangia (spore cases) that

are

aggregated into readily visible clusters called "sori." On many ferns,

the sori are located on the leaf undersurface. In

the photo below, the very numerous tiny granular-looking sprorangia are

partly covered

by protective circular flaps of leaf tissue called "indusia."

Approximately 50 sori (each consisting of an indusium plus its

associated sporangia) are shown.

Christmas fern sori, May 29, 2005, Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio. When

the spores are

mature, the sporangia

rupture and the freed spores are flung away from the parent plant.

A lucky spore that lands somewhere moist and otherwise suitable

for

germination develops into a little fingernail-sized, flat,

indistinctive, vaguelly heart-shaped gametophyte. (A fern

gametophyte is sometimes called a "prothallus" because it is an

undifferentiated plant, i.e., a thallus,

that proceeds

the fern.) Embedded in the prothallus are separate vessel-like

structures that

produce sperm, and eggs. Fern sperm travel from one

gametophyte to another, where an egg awaits, through environmental

water. This is one reason why many ferns are restricted to moist

places.

After fertilization, the developing embryo sporophyte stays briefly attached and nutritionally dependent on the maternal gametophyte. Eventually the new fern sporpphyte is large enough to persist on its own, and then the tiny used-up gametophyte withers away. Here's a picture showing baby Christmas fern sporophytes still attached to the maternal gametophytes that produced them.  Flat undifferentiated Christmas fern gametophyte (prothallus) with leafy young sporophyte attached. October 22, 2007, Chimney Rocks, Pike County, Ohio. But the Applachian gametophyte is atypical -- It completely lacks a sporophyte! Dark

moist recesses in

non-calcareous rock

in the Appalachian Mountains and Appalachian Plateau regions of the

Eastern United States may be home to the gametophytes of Vittaria

appalachiana,

for which sporophytes are completely unknown. Because they are able to

multiply by means of miniscule fingerlike projections that break off

and serve as asexual reproductive structures (gemmae), there is no

longer a need for sporophytes. There is no

expectation that sporophytes will ever be found. The species

has lost the ability to reproduce sexually.

In the Hocking Hills region of southern Ohio, there are caves and crevices beneath sandstone overhangs that are perennially cool and moist, consituting ideal conditions for the Appalachian gametophyte.  Cave in sandstone overhang, Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio, September 19, 2008. The deepest darkest recess is the habitat of the Applachian gametophyte, Vittaria applachiana.  Gametophyte's-eye view of the cave habitat of the Appalachian gametophyte.  Appalachian gametophyte on sandstone cave wall, September 19, 2008, Hocking County, Ohio.  Appalachian gametophyte with fingerlike asexual gemmae, September 19, 2008, Hocking County, Ohio. |