(Additional content at flickr Photostream and YouTube Channel)

If you have botany questions or comments please email BobK . Thanks!

"Ground-nut"

has a weirdly

colored flower

Pickaway County, Ohio, August 22, 2009.

Pickaway County, various dates during August 2009

At Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve in Pickaway County, Ohio, a lovely meadow lies between the woodland and the marshy pond edge where rose-mallows grow. During trips I took to Stage's this summer studying the pollination biology of the mallows it was a treat to walk through this successional field, and see the progression of mid to late summer wildflowers and their associated arthropods.

The "bowl and doily" spider, Frontinella communis (family Linyphiidae, the sheetweb weavers) constructs a distinctive two-part web. Above, there is an inverted dome, the "bowl". The bowl is not very sticky, but its owner perches upside-down beneath the bowl watching vigilantly, and swiftly bites through the bowl to seize and then wrap up any hapless critter that falls into it. The lower "doily" web may serve as protection from predators. These spiders, and their quite conspicuous webs, are often very abundant in densely vegetated sunny places.

Field

Trip to Arborvitae Fen

Champaign County, Ohio. August 18, 2009

Pickaway County, Ohio, August 22, 2009.

Apios americana

is a native vine in

the Fabaceae (pea/bean/legume family). It bears 5-7 parted

pinnately compound leaves, and racemes of moderately large

flowers that are predominantly brown-purple.

Ground-nut at "Calamus Swamp," Pickaway County, Ohio. August 22, 2009.

Ground-nut at "Calamus Swamp," Pickaway County, Ohio. August 22, 2009.

The

small underground

potato-like ground-nut tubers are

regarded as choice edible items, said to have been a staple of Native

Americans. (Note: the name "ground nut" is also

used

for a wholly different legume --the peanut (Arachis

hypogaea) --in many parts of

the world.) I've never tried Apios

tubers, but would like to.

The flowers are interesting, an odd color.

Ground-nut flowers. August 22, 2009. Pickaway County, Ohio.

Mid-Ohio

Meadow

MiscellanyThe flowers are interesting, an odd color.

Ground-nut flowers. August 22, 2009. Pickaway County, Ohio.

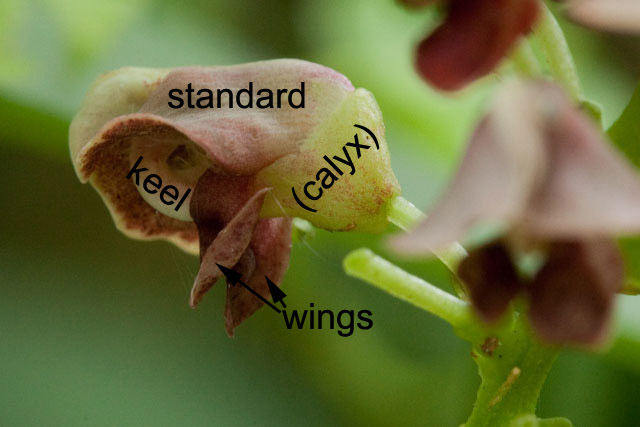

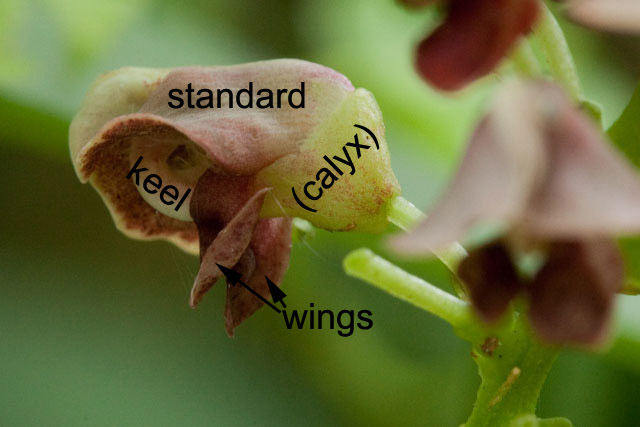

The

flowers of the Fabaeae

have distinctive petals. Uppermost is the large, solitary "banner"

(also called the "standard"). On the sides are the two medium-sized

"wings." Lowermost are two small petals fused at the tip, comprising a

structure called the "keel" that closely envelops the sexual parts of

the flower (pistil and stamens).

Here's a closeup with the petals labelled.

Apios americana flower with parts labelled.

Here's a closeup with the petals labelled.

Apios americana flower with parts labelled.

Pickaway County, various dates during August 2009

At Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve in Pickaway County, Ohio, a lovely meadow lies between the woodland and the marshy pond edge where rose-mallows grow. During trips I took to Stage's this summer studying the pollination biology of the mallows it was a treat to walk through this successional field, and see the progression of mid to late summer wildflowers and their associated arthropods.

The "bowl and doily" spider, Frontinella communis (family Linyphiidae, the sheetweb weavers) constructs a distinctive two-part web. Above, there is an inverted dome, the "bowl". The bowl is not very sticky, but its owner perches upside-down beneath the bowl watching vigilantly, and swiftly bites through the bowl to seize and then wrap up any hapless critter that falls into it. The lower "doily" web may serve as protection from predators. These spiders, and their quite conspicuous webs, are often very abundant in densely vegetated sunny places.

MOUSEOVER

the IMAGE to see ZOOM-CROP of SPIDER

Bowl and doily at Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve. August 5, 2009.

Bowl and doily at Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve. August 5, 2009.

Taken

from beneath, looking

up, here's what the spider looks like, on guard duty.

Bowl and doily spider at Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve. August 5, 2009.

Bowl and doily spider at Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve. August 5, 2009.

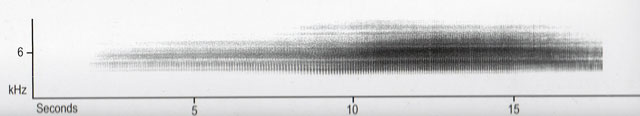

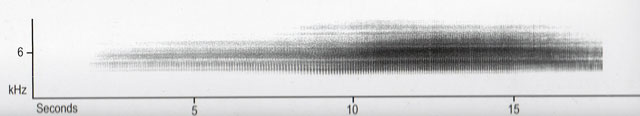

A

great population of a delightfully noisy "annual" cicada (with adults

emerging every year, in contrast with the 13-year and 17-year

"periodical" ones) lives in the meadow and marsh. It's the

swamp cicada, Tibicen chloromera,

in the insect order Homoptera. According to Lang Elliot and Will

Hershberger in their terrific book "The Songs of Insects" (2007,

Houghton Mifflin), this species is "the only eastern species that is

frequently found on low weedy vegetation and shrubs in swamps or marshy

habitats, as well as in dry upland meadows and overgrown fields." They

go on to say "It should perhaps be renamed "Morning Cicada" because of

its striking habit of singing from early morning until noon, with very

little singing in the afternoon." Among the 5 species in our

area Lang and Hershbergber include in their book because they

are most likely to be heard, this one is distinguished by its

dark body with bright green patches on the head, and prominent

blue-green wing veins.

Swamp cicada at Stage's Pond, Pickaway County, Ohio. August 22, 2009.

Swamp cicada at Stage's Pond, Pickaway County, Ohio. August 22, 2009.

Apparently

cicadas are fairly easy to identify by song. This one

is described as "a soft buzz that gradually changes into a

pulsating drone that increases in volume to a cresendo, and then

gradually tapers off before ending abruptly. Song length is ten to

fifteen seconds, with a peak frequency of around 6 kHz. Here's a copy

of the sonogram from Will and Herschberger's book, that you should buy

and enjoy even if, like me, you discover to your chagrin and dismay

that your old ears cannot hear many of the songsters

--especially various katydids and long-horned

grasshoppers --because they're way too high pitched!

Swamp cicada sonogram

from "The Songs of Insects."

Here's

a video of the swamp cicada, singing merrily.

Swamp cicada at Stage's

Pond State Nature Preserve. August

23, 2009. The

pasture thistle, Cirsium discolor

(family

Asteraceae) is a magnet for interesting pollinators. Among them,

bumblebees. Here are two instances of apparently different species of

bumblebee. Bumblebee ID doesn't seem simple enough for me to name them

right now, or perhaps ever.

One of them is patterned simply, with an abdomen that is yellow in the front half, black at back.

Pasture thistle with a bumblebee. (Soldier beetle in background). August 22, 2009.

Pasture thistle with another bumblebee. August 22, 2009.

One of them is patterned simply, with an abdomen that is yellow in the front half, black at back.

Pasture thistle with a bumblebee. (Soldier beetle in background). August 22, 2009.

...while

another bumblebee

has a striped abdomen, with yellow more predominant.

Pasture thistle with another bumblebee. August 22, 2009.

Perched

atop an unopened

flower head of the thistle (note the distinctively spiny phyllaries of

this thistle), a wasp. Judging by the extensive ovipositor, this is

probably one of the many "parasitic hymenoptera" that lay eggs inside

the body of living insects which then are devoured from within.

Ichneumon wasps are the most well known of these.

Parasitic wasp on pasture thistle.

August 22, 2009. Stage's Pond.

Parasitic wasp on pasture thistle.

August 22, 2009. Stage's Pond.

A

hummingbird hawkmoth, Hemaris thysbe,

hovers while

foraging.

Hummingbird hawkmoth foraging on pasture thistle.

Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve. August 22, 2009.

Hummingbird hawkmoth foraging on pasture thistle.

Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve. August 22, 2009.

...and

another "lep" (member

of the insect order Lepidptera), extremely common, is the silver-spotted skipper, Epargyreus clarus.

Silver-spotted skipper on pasture thistle at Stage's Pond. August 22, 2009.

Silver-spotted skipper on pasture thistle at Stage's Pond. August 22, 2009.

Champaign County, Ohio. August 18, 2009

It was great

fun tagging along on another OSU "Local

Flora"

(EEOB 210) class field trip, this time to Cedar Bog, a 426-acre remant

boreal fen situated in the Mad River Valley, Champaign County,

west-central Ohio. The preserve, one of Ohio's premier natural areas,

is an Ohio Historical Society site managed by the Cedar Bog

Association, a nonprofit organization that serves the public in

preserving and interpreting the natural history, geology and history of

Cedar Bog.

OSU "Local Flora" class at Cedar Bog Nature Preserve, Champaign County, Ohio.

According to information

provided on their excellent

infomative

web site, the

area was first known as "Cedar Swamp." But since a swamp is a wooded

wetland, and the area is dominated by herbaceous plants, the name got

changed to "Cedar Bog." But, as the stewards of the site explain very

well, it's a fen, not a bog.

A fen is a calcareous (high pH --the opposite of acidic --which is why it's a fen, and not a bog) wetland that derives its water from ground water pushing up through calcium-rich surface soil. Fens are occupied, in large part, by characteristic species with a strong fidelity to alkaline wetlands. We saw many of them.

On the way to the fen though, we enountered some decidely non-fen plants gracing the edges of some disturbed ground near the visitor center. Both in the genus Ambrosia (food of the gods?), they grow side-by-side. It's always fun to see congeneric species co-occuring.

A fen is a calcareous (high pH --the opposite of acidic --which is why it's a fen, and not a bog) wetland that derives its water from ground water pushing up through calcium-rich surface soil. Fens are occupied, in large part, by characteristic species with a strong fidelity to alkaline wetlands. We saw many of them.

On the way to the fen though, we enountered some decidely non-fen plants gracing the edges of some disturbed ground near the visitor center. Both in the genus Ambrosia (food of the gods?), they grow side-by-side. It's always fun to see congeneric species co-occuring.

Two ragweeds at Cedar Bog, Urbana, Champaign County, Ohio August 18, 2009.

The two species are giant

ragweed, A.

trifida, and common ragweed, A.

artemisiifolia; both are

common weeds of waste places. As native

plants, they deserve a bit more respect than they are usually afforded.

Their habitat --open areas --must have occurred sparingly as the result

of big trees being wind-thrown, streambank erosion, and

rockslides when North

America was forest primeval.

Now sunny bare soil conditions are preavalent owing to anthropogenic

disturbance, so the plants are common, too. We don't much like them,

perhaps because we don't like the environmental degradation they

follow. Here are portraits of the two ragweeds.

Two ragweeds. Left: Ambrosia trifida. Right: Ambrosia artemisiifolia.

Cedar Bog Nature Preserve. Urbana, Champaign County, Ohio. Auguest 18, 2009.

In

terms of pollination

ecology, ragweed is much like oak, walnut and hickory. All these plants

are monoecious (i.e., bearing unisexual flowers, with both

sexes

present on every plant), and wind-pollinated. They present their

very numerous, very small, male flowers on elongate stems, but

produce only a few female flowers, which are much larger than the male

ones. The picture below, taken during September a few years ago at a

central Ohio prairie, shows giant ragweed in fruit.

Giant ragweed in fruit. Note plump fruiting pistillate heads just beneath spent staminate heads.

The male heads are on an elongate racemiform inflorescence. Marion, Ohio. September 12, 2005.

Giant ragweed in fruit. Note plump fruiting pistillate heads just beneath spent staminate heads.

The male heads are on an elongate racemiform inflorescence. Marion, Ohio. September 12, 2005.

The Cedar Bog fen is an open area dominated by graminoids, richly infused with lovely forbs.

Fen habitat at Cedar Bog Nature Preserve. August 18, 2009.

One of the graminoids

--perhaps the dominant species here --is a sedge

(family Cyperaceae) named, in slightly misleading fashion since it is a

sedge (family Cyperaceae), not a rush (Juncaeae) "twig-rush," Cladium mariscoides.

Twig-rush at Cedar Bog. August 18, 2009.

Somewhat

more colorful

wildflowers are in bloom. One is swamp lousewort, Pedicularis lanceolata,

traditionally placed in the

figwort family (Scrophulariaceae). The louseworts, of which there

are two species in Ohio, have somewhat fern-like foliage, and

large bumblebee-pollinated fowers. More correctly/recently placed in

the "broom-rape" family Orobancaceae, these are "hemiparasites,"

deriving some of their nutrition from underground connections to

neighboring plants. It's odd. They don't look

like parasites. They're green.

And about that name --lousewort. Usually when a plant has some creepy thing as part of its name, it's based on some ancient belief the plant cures the creepy thing. But for lousewort, au cointraire! Both the genus, from the Latin pediculus, meaning "louse," and the common name are based on an old superstitious belief that, after eating the plants, grazing cattle had more lice! It's definately a lousy name. Pedicularis is also called "wood betony." Isn't that better?

And about that name --lousewort. Usually when a plant has some creepy thing as part of its name, it's based on some ancient belief the plant cures the creepy thing. But for lousewort, au cointraire! Both the genus, from the Latin pediculus, meaning "louse," and the common name are based on an old superstitious belief that, after eating the plants, grazing cattle had more lice! It's definately a lousy name. Pedicularis is also called "wood betony." Isn't that better?

Kalm's

lobelia, Lobelia

kalmii

(bellwort family, Campanulaceae) is a northern species ranging across

the continent. It is at a southern boundary of its range in Ohio, where

it occurs mainly in northern and central counties in fens, marl bogs,

and wet shale cliffs.

Fabulous

fen forbs. Cedar

Bog. August 18, 2009.

Left: Swamp lousewort. Right: Kalm's lobelia.

Left: Swamp lousewort. Right: Kalm's lobelia.

Cowbane, Oxypolis rigidior, is a white-flowered "umbel" (member of the parsely family, Apiaceae) that bears a striking similarity to water-parsnip, Sium suave. Both are smooth wetland herbs with pinnately compound leaves. Here for comparison they are presented side-by-side: Cedar Bog's Oxypolis, and Sium as seen two years ago in a wet central Ohio woodland.

Lookalike umbellifers.

Left: Oxypolis rigidior at Cedar Bog, Champaign Conty, Ohio. August 18, 2009.

Right (for comparison): Sium suave at Stage's Pond, Pickaway County, Ohio. August 26, 2006.

To

distinguish these guys,

note the leaflets of Oxypolis

are entire (or have a few coarse teeth along each margin), whereas

those of Sium

are

completely toothed. Here's a Sium

leaf,

smiling for the camera

(showing its teeth).

Sium suave leaf showing serration absent on Oxypolis leaves.

Stage's Pond, Pickaway County, Ohio. August 26, 2006.

Sium suave leaf showing serration absent on Oxypolis leaves.

Stage's Pond, Pickaway County, Ohio. August 26, 2006.

...and

here's another pic of Oxypolis,

on which it may be

evident that the leaflet margins are entire.

Oxypolis at Cedar bog. Note entire (untoothed) leaflets.

August 18, 2009. Champaign County, Ohio.

The

umbels of cowbane are

loose and open, compound, and, in this specimen at least, lack any

bracts beneath the primary umbel. It has slender inconspicuous

bractlets beneath the secondary umbels.

Oxypolis inflorescence, a compound umbel, at Cedar Bog. August 18, 2009.

Oxypolis inflorescence, a compound umbel, at Cedar Bog. August 18, 2009.

Although its frequent occurence as a cultivated shrub outside "fast food" restaurants somewhat diminishes its charm, shrubby cinquefoil, Potentilla fruticosa (family Rosaceae, the rose family) in its native manifestation is an admirable, fairly uncommon, habitat specialist. Shrubby cinguefoil is a denizen mainly of wet meadow and marly bogs (fens). Note the pubescent leaves with 5-7 narrow leaflets.

Shrubby cinquefoil at Cedar Bog, Champaign County, Ohio. August 18, 2009.

Fens and prairies have a similar geologic history, and many species in common, such as prairie dock, Silphium terebinthinaceum (aster family, Asteraceae).

Prairie dock at Cedar Bog. August 18, 2009.

Like

other "asters," Silphium

produces flowers that are

individually minute, aggregated into head-like flower clusters that

simulate an individual blossom.

Prairie dock heads. August 18, 2009.

Prairie dock heads. August 18, 2009.

Like

many other aster family

members --sunflowers (Helianthus)

are another clear example --Silphium produces

its flowers in a

type of capitulum that is termed "radiate" because the little

individual flowers are of two types: (1) in the center

are radially symmetric "disk" flowers, and (2) at the

periphery,

resembling

the petals of the big individual blossom the capitulum

pretends to

be,

are the strap-shaped "ray" flowers.

Silphium capitula are rather peculiar, though. Instead of, like sunflower, having the disk flowers perfect (hermaphroditic) and the showy ray flowers neuter, Silphium flowers are unisexual. The disk flowers, with a surprisingly long but unbranched style, are staminate (male)! (I wonder what is the function of this conspicous style. Is it a handle for bumblebees to grab onto while foraging?) The pistillate (female) flowers, with a short branched style, and no stamens, are the ray flowers.

Silphium terebinthinaceum young capitulum. August 18, 2009.

Silphium capitula are rather peculiar, though. Instead of, like sunflower, having the disk flowers perfect (hermaphroditic) and the showy ray flowers neuter, Silphium flowers are unisexual. The disk flowers, with a surprisingly long but unbranched style, are staminate (male)! (I wonder what is the function of this conspicous style. Is it a handle for bumblebees to grab onto while foraging?) The pistillate (female) flowers, with a short branched style, and no stamens, are the ray flowers.

Silphium terebinthinaceum young capitulum. August 18, 2009.

After

flowering, the

staminate flowers are shed. This late-stage older prairie-dock head

displays only four of them remaining. Meanwhile the ray flowers are

retained, as they are developing into one-seeded fruits (achenes).

Silphium terebinthinaceum older capitulum. August 18, 2009.

Silphium terebinthinaceum older capitulum. August 18, 2009.

A

couple of other uncommon asters with an affinity for wetlands are

flowering today. One of these is swamp thistle, Cirsium muticum.

Among our native thistles, this one's a pacifist: the only species

entirely lacking spines on the involucral bracts.

Swamp thistle at Cedar Bog. August 18, 2009.

Swamp thistle at Cedar Bog. August 18, 2009.

...another

is Ohio goldenrod, Solidago ohioensis.

Note its distinctive flat-topped growth form.

Ohio goldenrod at Cedar Bog. August 18, 2009.

Ohio goldenrod at Cedar Bog. August 18, 2009.

A

rather rare shrub, our only

shrubby member of the genus Betula

is swamp birch, Betula pumila

(family Corylaceae). This is a northern bog shrub occuring as a glacial

relict at a few places in west-central and northeastern Ohio.

Swamp birch at Cedar Bog, Champaign County, Ohio. August 18, 2009.

Swamp birch at Cedar Bog, Champaign County, Ohio. August 18, 2009.

...and

speaking of woody

plants, and the name of this preserve, consider the following. Cedar

Bog, which isn't a swamp, used to be called "Cedar Swamp." So they

changed the name to "Cedar Bog" even though it isn't a bog. OK, some

day they'll change the name to "Cedar Fen," and all will be well and

good, right?

See...there are cedars growing here. But the species is northern white cedar, Thuja occidentalis (also called "arbor vitae") (family Cupressaceae), a widespread coniferous small tree, interesting in many ways. With foliage high in vitamin C, it cured scurvy among some early explorers in North America, and as a result became the first forest tree to be imported from North America to Europe. In our region the species is a calciphile, but it occupies strikingly different habitats: very dry limestone-based soil such as at Clifton Gorge in Greene County, and squishy gushy places like this. The species is often heavily browsed by deer.

But is Thuja a cedar? Technically, no, as the only "true cedar" is Cedrus, a strictly old world genus. The various North American cedar-like plants are close, but no cedar-gar. Thuja is indeed "northern white cedar," Juniperus virginiana is "red cedar," and, going farther afield, the eastern Chamaecyparis is "Atlantic white cedar," and the western Libocedrus is "incense-cedar." So when the Ministry of Truth publishes the Newspeak guide to this preserve it will be "Arbor Vitae Fen," and we will say "We are at Arbor Vitae Fen, we've always been at Arbor Vitae Fen, and we're at war with Clifton Gorge. We've always been at war with Clifton Gorge." (Sorry, I just finished an audio book of "1984" and it's gotten stuck in my head.) Bog Brother is watching you!

In the woods adjacent to the fen is an uncommon tree of swampy woods --the most northern of the ashes --black ash, Fraxinus nigra (family Oleaceae, the olive family). The ashes aren't very easy to tell apart. This one is distinguished by having its leaflets sessile (unstalked).

Black ash sapling at Cedar Bog Nature Preserve. August 18, 2009.

Instructions for an EAB Halloween costume. Columbus Dispatch. October 25, 2009.

The Araliaceae (ginseng family), with its compound leaves and small 5-merous epigynous flowers in an umbel type of inflorescence, seems quite close to the Apiaceae (parsely family). The fruit type is very different: a berry in the Araliaceae, and a 2-parted dry fruit that splits into 1-seeded segments, called a schizocarp, in the Apiaceae. Here's spikenard, Aralia racemosa, in the Araliaceae. It's a moderately common woodland herb.

Spikenard at Cedar Bog Nature Preserve. August 18, 2009.

Spikenard at Cedar Bog Nature Preserve. August 18, 2009.

See...there are cedars growing here. But the species is northern white cedar, Thuja occidentalis (also called "arbor vitae") (family Cupressaceae), a widespread coniferous small tree, interesting in many ways. With foliage high in vitamin C, it cured scurvy among some early explorers in North America, and as a result became the first forest tree to be imported from North America to Europe. In our region the species is a calciphile, but it occupies strikingly different habitats: very dry limestone-based soil such as at Clifton Gorge in Greene County, and squishy gushy places like this. The species is often heavily browsed by deer.

Eponymous

northern white

cedar at Cedar Bog. August 18, 2009.

But is Thuja a cedar? Technically, no, as the only "true cedar" is Cedrus, a strictly old world genus. The various North American cedar-like plants are close, but no cedar-gar. Thuja is indeed "northern white cedar," Juniperus virginiana is "red cedar," and, going farther afield, the eastern Chamaecyparis is "Atlantic white cedar," and the western Libocedrus is "incense-cedar." So when the Ministry of Truth publishes the Newspeak guide to this preserve it will be "Arbor Vitae Fen," and we will say "We are at Arbor Vitae Fen, we've always been at Arbor Vitae Fen, and we're at war with Clifton Gorge. We've always been at war with Clifton Gorge." (Sorry, I just finished an audio book of "1984" and it's gotten stuck in my head.) Bog Brother is watching you!

In the woods adjacent to the fen is an uncommon tree of swampy woods --the most northern of the ashes --black ash, Fraxinus nigra (family Oleaceae, the olive family). The ashes aren't very easy to tell apart. This one is distinguished by having its leaflets sessile (unstalked).

Black ash sapling at Cedar Bog Nature Preserve. August 18, 2009.

Ashes

are being wiped out on a grand scale by an Asian beetle, the emerald

ash borer (EAB). At the time of this writing (late October), the

Columbus

Dispatch ran a set of instructions for making some uber-cute

Halloween costumes, and one of them is EAB! Behold.

Instructions for an EAB Halloween costume. Columbus Dispatch. October 25, 2009.

The Araliaceae (ginseng family), with its compound leaves and small 5-merous epigynous flowers in an umbel type of inflorescence, seems quite close to the Apiaceae (parsely family). The fruit type is very different: a berry in the Araliaceae, and a 2-parted dry fruit that splits into 1-seeded segments, called a schizocarp, in the Apiaceae. Here's spikenard, Aralia racemosa, in the Araliaceae. It's a moderately common woodland herb.

Spikenard at Cedar Bog Nature Preserve. August 18, 2009.

Here's

a closer view, showing the berries of spikenard.

Spikenard at Cedar Bog Nature Preserve. August 18, 2009.