|

|

Welcome

to bobklips.com, the website of Bob Klips, a plant enthusiast living in

Columbus, Ohio. ..................................................................................................................... Manuka oil!

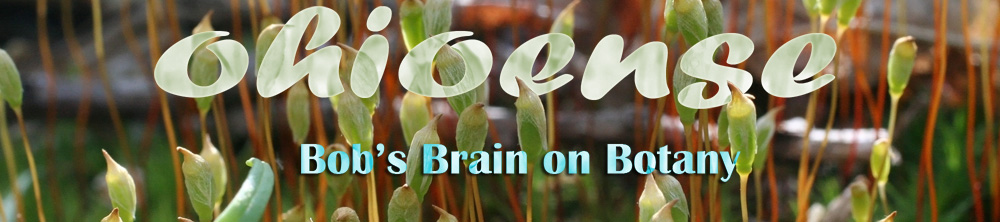

June 29, 2009. Lucas County,Ohio (more on the emerald ash borer) Manuka (Leptospermum

scoparium, Myrtaceae, the myrtle family) is a New

Zealandish shrub, the source of an oil popular among those who employ

herbal

remedies. According to one

web site promoting its use,

preparations made from manuka leaves have long been used by the Maori

people to cure a variety of ailments such as urinary complaints and

head

colds, as well as as a "febrifuge" (fever-reducer).

The bark is used along with the leaves to concoct a muscle and

joint-soothing salve, or it is or simply chewed as a relaxing

sleep-enhancer. Nowadays, and more widely, a very aromatic concentrated

oil made by steam-distilling manuka leaves and small twigs is sold for

its

antibacterial, antifungal, anti-inflammatory and anti-acne

properties. A major active ingredient is leptospermone.

***Study hint for the upcoming pharmacology quiz: If you don't know the name of a plant-derived chemical, simply take its genus name and add "-one" or some similar cognate at the end. It works every time! Well, not every time really...but every so often at least. Here are some examples:  Some

instances of

plant-derived chemicals the names of which are similarly derived.

Manuka oil is also used in aromatherapy. People love manuka oil because it smells like a stressed and dying ash tree! Well, not people maybe, but apparently emerald ash borers do, because manuka oil is a great attractant for detecting the presence of the metalic wood boring (Buprestid) beetle Agrilus planipennis. How do they discover these things? A pad saturated with the oil is used inside sticky traps made of cardboard-like plastic pyramidal cones hung from ash trees in areas where EAB researchers are assaying the abundance of the pests. The traps are purple because purple is the beetle's favorite color. How do they discover these things? This day I had the pleasure of accompanying USDA Forest Service and OSU researchers at the Oak Openings Metropark in Lucas County (northwest Ohio, near Toledo). The sites we visited were low-lying areas, formerly forested, where green ash was predominant.  EAB researchers employing aromatherapy. Oak Openings Metropark, Lucas County Ohio. June 29, 2009. The trap at

this

location don't have very

many beetles stuck to it, mainly because the beetles have already "been

there,

done that." Since there are no living ash trees of substantial size

remaining --the

devastation is awful --the emerald ash borer is scarce there now. The

photo below shows the extent of the tree loss.

Devastated lowland ash forest in Lucas County, Ohio. June 29, 2009. By contrast, at a study site in central Ohio where the beetles arrived only in the past year or two, they are thriving. The pictures below show a stinky sticky purple trap high up in a tree at the Stratford Ecological Center in Delaware, Ohio.  EAB trap at Stratford Ecological Center. July 14, 2009. ...and a bunch of beetles stuck to it. Its interesting they are all on their backs. Do they approach the traps that way, or do they struggle to get free in a manner that ultimately gets them more stuck, on their backs?  Emerald ash borers on sticky trap at Stratford Ecological Center. July 14, 2009. At Oak

Openings Metropark, the newly

created no-ash openings seem peculiar as they are occupied by

plants normally found in shadier places (as they were

until

quite recently, thanks to the borers). It was nice to see

green

dragon, Arisaemia dracontium, family Araceae, in

fruit.

Green dragon at Oak Openings Metropark. June 29, 2009. Green dragon

is in the same genus as Jack-in-the-pulpit (A.

triphyllum). It has a very intriguing leaf complexity

--compound, but divided into two main segments, each

of which is further subdivided into leaflets totalling 7-13 in number.

This composition, termed "pedately divided," is like that of

maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum).

Green dragon leaf. Oak openings Metropark. June 29, 2009. The green

dragon

flowers are arranged

in typical aroid fashion, wherin the flowers are small, and

aggregated over part of a fleshy spike termed the "spadix" (Preacher

Jack is a spadix.) subtended by a large leaflike bract, the "spathe"

(Jack's pulpit is a spathe.). In fruit, it displays a cluster of

berries that will eventually turn orange-red.

Green dragon young fruit. June 29, 2009. Lucas County, Ohio. Here's what

green

dragon looked like in flower, in a picture taken six weeks and four

years ago.

Green dragon as it appeared in flower, mid-May (2004). The wetter

spots are

home to a very

dramatic sedge that looks like a collection of midieval maces.

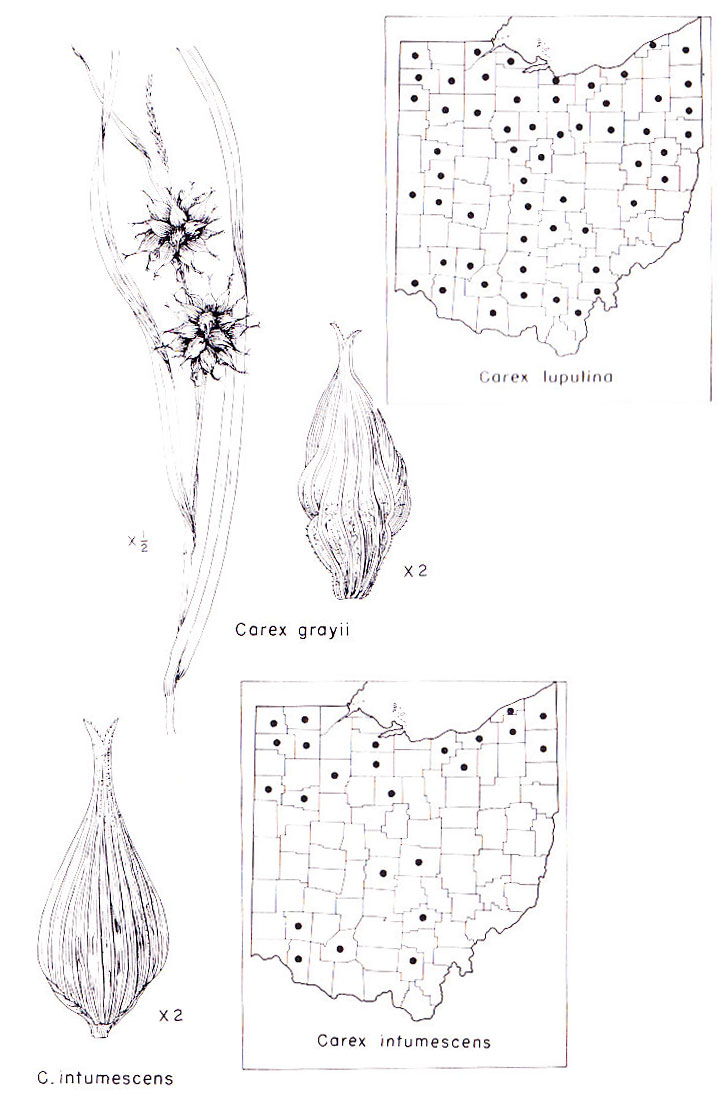

From a online weapons shop for reenactors (I hope so anyhow): a collection of midieval maces In the Lupulinae section of the genus Carex, this is either Gray's sedge (Carex grayii) or bladder sedge (C. intumescens). Both species bear a few large wholly pistillate spikes of a globose shape composed of relatively few, relatively large, perigynia (perigynia are the papery-covered single seeded fruit units characteristic of Carex) and a long narrow terminal spike that is entirely staminate. After that is gets confusing.  Carex grayii or C. intumescens at Oak Openings Metropark. June 29, 2009. ...confusing

because

while in the field I was sure this was Carex grayii,

a species which which I was long familiar (or at least thought I was).

Another botanist in the group suggested it might be Carex

intumescens

but I rudely scoffed at that idea, thinking is was just the result of

his having inhaled too much manuka oil. It can do that to you.

But

now that it's time to label the photos and present them here,

consultation with E. Lucy Braun through her excellent

1967 Ohio

monocots book casts this identification in a different light. It turns

out there are indeed two mace-headed carices in our area!

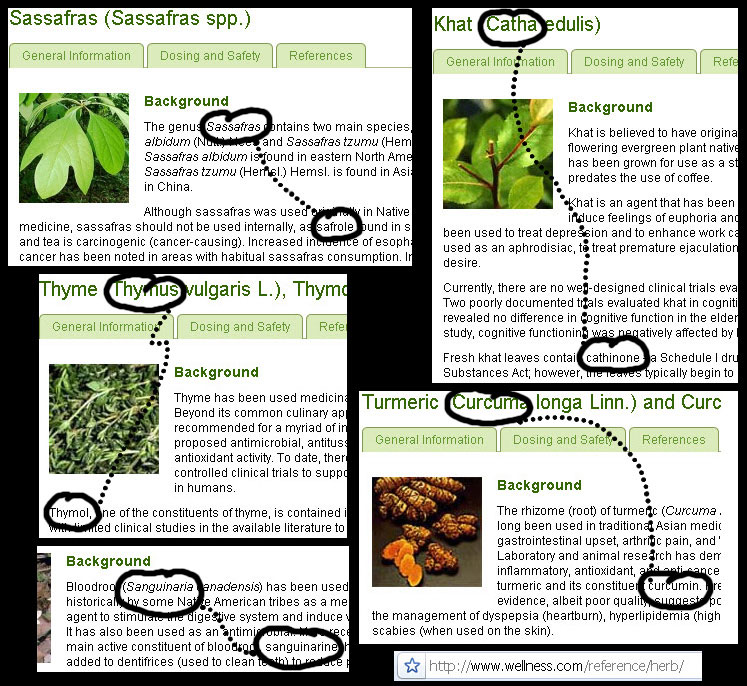

Carex

section lupulinae key in The Monocotyledonae of Ohio.

Arghh. She's

asking

about details of the

pergynium best seen by looking at a specimen through a hand lens, not a

picture of a specimen. But perhaps the "megapixel wars" are good for

something. Here's a zoomed in view of another pic taken today.

Enlarged portion of sedge head. June 29, 2009. Oak Openings Metropark. While they

don't seem

hairy,

"hispidulous" could be missed in a photo like this. (Moreover --see

below --there are evidently glabrous-ruited forms of C. grayii.)

One thing at least: In this photo, these perigynia do certainly seem

"lustrous" (shiny), not "dull." That pushes it towards C.

intumescens! The situation is made totally worse by examining

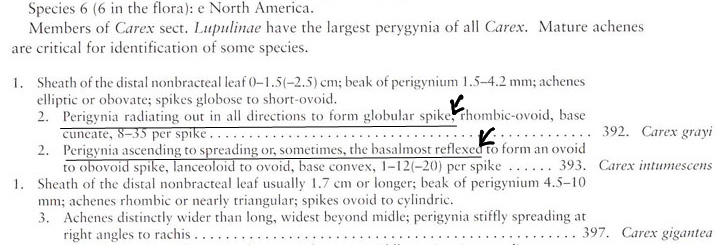

carefully the species descriptions in the Ohio monocots book.

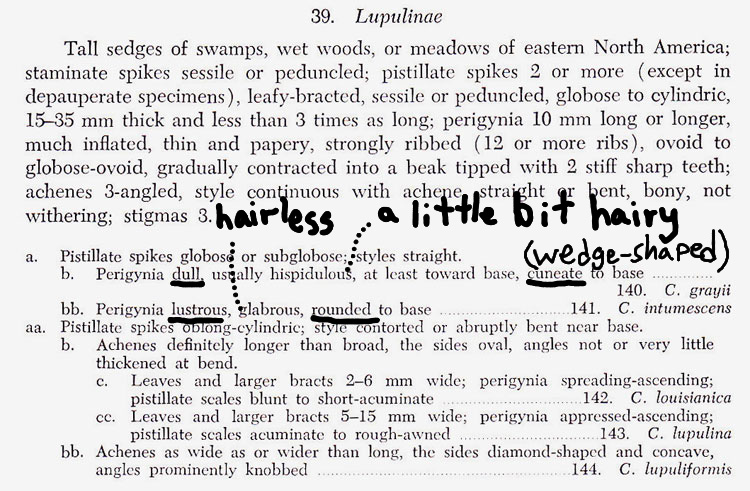

Species descriptions in Ohio monocots book. E. Lucy

tells us that C.

grayii has

perigynia radiating out in all directions. This can be observed in a

picture, and indeed they are. Usually the remarks at this stage in a

key are very species-specific. But there is, sadly, no explicit

complementary refererence to the head shape of C. intumescens,

implying that they are both equally globular. There are

perigynium measurments, making me wish that I had a specimen, but only

for a fleeting instant do I wish that because it always happens that,

if,

say, one species' perigynia are supposed to be 12-18 mm long and the

other's are given as 10-16 mm long, the perigynia on your

specimen will be 14 mm long, squarely within both ranges. Always.

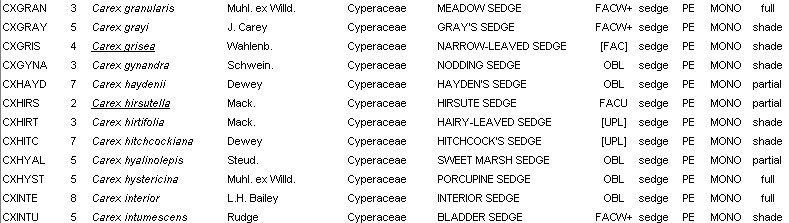

Mace-headed sedge pics and range maps from The Monocotyledonae of Ohio. The range

maps indicate

that either

species is possible in this area. Also, reference to the wonderfully

useful appendix to "Floristic

Quality Assessment Index (FQAI) for Vascular Plants and Mosses for the

State of Ohio,"

by Barbara Andreas, John Mack and James McCormac, 2004, Ohio

Environmental Protection Agency shows that both species have the same

wetness affinity, shade-tolerance, and middling "5" for their Coefficient

of Conservatism (an estimate of the degree to

which a species tends to occur only in specific habitat types.

These are mainly high-quality natural communities similar to those that

existed in pre-settlement times.)

Portion

of OEPA's Floristic Quality Assessment Index showing pertinent sedge

species.

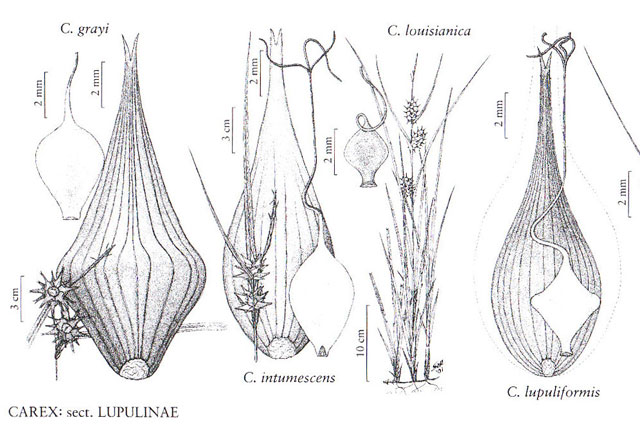

There

is hope perhaps by turning to another, more modern reference: volume 23

of the Flora of North America (FONA) North of Mexixo --Magnoliophyta:

Commelinidae (in part): Cyperaceae, publishd in 2002 by the Oxford

University Press. In it, A.A. Reznicek states explicity what E. Lucy

Braun hinted at and then backed away from. Yes Virginia, there

is a head-shape

difference between the two species!

"O.K. contestants and Jeopardy fans, the category is 'sedges' for $1000. ...These have the largest perygynia of all Carex." "Buzzzz" "Yes, A.A?" "What is section Lupulinae?!"  FONA excerpt showing differences betwen two mace-headed Carex species. ...and the

illustrations corroborate that, thankfully.

Mace-headed sedge pics from FONA So it seems, provisionally at least, that this mace-headed sedge is Carex grayi after all. If only www.bobklips.com were an nice interactive blog rather than a static website, then someone --perhaps Tim Walters, seen on the far left standing next to the EAB trap in the picture below, who teaches a yearly workshop on sedges and also has dozens of such species growing in his yard/garden--could post helpful sedge identification comments.  EAB researchers and their enthusastic followers at Oak Openings Metropark, Lucas County, Ohio. Below are images of some of the other woodland plants that are wondering who turned the lights on all of a sudden. Honewort (Cryptotaenia canadensis, family Apiaceae) is especially abundant.  Honewort at Oak Openings Metropark. June 29, 2009. Tall

meadow-rue (Thalictrum

dasycarpum, family Ranunculaceae) is a dioecious (i.e.,

having separate male and female individuals) herb.

Tall meadow-rue at Oak Openings. June 29,. 2009. Left: Pistillate (female) plant. Right: Staminate (dude) plant. ...closer

views of the

meadow-rue flowers.

Tall meadow-rue flowers at Oak Openings. June 29,. 2009. Left: Pistillate (female) flowers. Right: Staminate (dude) flowers.  Canada avens flower. Oak Openings Metropark. June 29, 2009. Ohio is home

to five

native species of Rosa

(family Rosaceae), plus six alien ones. Our most

distinctive native is climbing prairie rose, R. setigera.

Rose setigera. June 26, 2009. Wyandot County, Ohio. The first

important

subdivision in E. Lucy Braun's excellent rose key in The

Woody Plants of Ohio (OSU Press; 1961, 1989) asks whether or

not the styles are united, forming a column exserted from the throat of

the receptacle. Rosa setigera indeed displays this

trait. Below are images showing the styles of Rosa

setigera and another rose --R. carolina

--that

doesn't have the styles so united.

Roses are very stylish! Left: Rosa setigera showing styles united into column. Right: Rosa carolina showing styles shorter, covering throat of receptacle. Rosa setigera is our only native rose with styles of this form. Also, it has large pink flowers, and leaves that are nearly always 3-foliolate (i.e., composed of 3 leaflets). Today the flowers are being visited by (presumably) native pollen-gathering bees (video). Climbing prairie rose and pollen-gathering bee. July 5, 2009. Incidentally,

one of

the nastiest

invasives is also in the small group of roses hacing an exsert column

of styles. This is the dreaded evil multiflora rose (R.

multiflora).

It has small white flowers. This picture, with a hidden spider I didn't

notice until long afterwards, was taken in early June last year.

Dreaded evil multiflora rose displaying its style column. June 8, 2008. Marion County, Ohio. Absent

flowers,

malevolent neer-do-well

multiflora rose can be neatly recognized by a vegetative feature:

ragged-edged (fimbriate) stipules. Stipules, paired

leaflet-like stuctures at the very base of a leafstalk, are a hallmark

of

the Rosaceae that is especially evident in roses proper.

Distinctive fimbriate stipules of terrible demonic multiflora rose. Japanese

honeysuckle

June 23,

2009. Columbus, Ohio

Japanese

honeysuckle (Lonicera

japonica,

family Caprifoliaceae) is a twining or trailing vine that H.A.

Gleason, in the best book ever written (The New Britton and Brown

Illustrated Flora...) aptly describes as "oppresively

abundant; native

of east Asia. May-Sep. Its densely tangled stems are capable of

smothering and destroying shrubs and small trees." Here's a picture of

its twining stems going up a tree a few years ago in northern Ohio.

Japanese honeysuckle twining. March 25, 2009. Cuyahoga County, Ohio. The species

is

flowering profusely now in

central Ohio, displaying well the features of its family, the

Caprifoliaceae. The honeysuckle family consists mainly (in our area at

least) of shrubs with opposite leaves. The three predominant local

genera can be distinguished simply on

vegetative traits

alone. Viburnums (genus Viburnum) and honeysuckles (Lonicera)

both have simple leaves. Those of viburnum have serrate

(toothed)

margins (in some species they are lobed as well), whereas honeysuckle's

leaves have entire margins. Contrastingly, the leaves of elderberry (Sambucus)

are pinnately compound (suggestive of ash).

Major genera of the Caprifoliaceae. Left to right: Viburnum, Lonicera, Sambucus.  Japanese honeysuckle displaying strongly zygomorphic (bilateral) flower symmetry. Columbus, Ohio. June 23, 2009. A more

detailed view of

the flowers shows

the 5 stamens (per flower) consisting of elongate curved filaments

tipped by oblong-linear anthers (pollen sacs), and the single, slightly

longer and straighter style tipped by a capitate

pollen-receptive

stigma.

Japanese honeysuckle stamens, style and stigma. June 23, 2009. Columbus, Ohio. An

interesting

honeysuckle trait is the

manner in which the flowers are arranged --in pairs, with each flower

sessile (stalkless), and the ovaries somewhat united. Here's a closeup

of a pair of Japanese honeysuckle flowers taken a few years

ago,

also in central Ohio.

Paired inferor ovaries of Japanese honeysuckle. Aug 30, 2006. Pickaway County, Ohio. After

pollination has

occurred, the

flowers fade to yellow as a signal to pollinating insects that the

flower is "sold out" of nectar, and they ought to look elsewhere for a

meal. The stamens wilt before the style. Perhaps sperm-delivering

pollen tubes are still growing down through the

style on

their way to the egg-containing ovules (future seeds) inside the ovary

(future fruit).

Senescent honeysuckle flower. June 23, 2009. Columbus, Ohio. Extrafloral

nectaries on Vicia

angustifolia

June 21,

2009 at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, Marion County, Ohio.

It can be confusing. "Extra" as a word simply means more of something, whereas "extra-" as a prefix signifies something that is outside or beyond. It is in this later sense of "extra" that some plants produce extrafloral nectaries. Vetchling (Vicia angustifolia, family Fabaceae) is an annual vine-like herb that bears alternately arranged pinnately compound leaves that end in a pair of tendrils. The flowers are paired in the upper axils of the leaves. A native of Europe, the plant is established in fields, roadsides and waste places. (What are waste places anyway?)  Narrow-leaved vetch in a roadside field (definitely not a waste place though) in Morral, Marion County, Ohio. June 21, 2009. Looking

carefully at

the blossoms, we see several traits typical of the legume (bean)

family.

[Note: In England and elsewhere, beans are called "pulses," and so the Fabaceae is known as the "pulse family." Q: Why did the cardiologist get arrested at the farmer's market? A: She took someone's pulse!] We see a calyx of five fused (connate) sepals, and a corolla that is strongly bilateral with so-called "papilionaceous" (i.e., resembling a butterfly) symmetry. The corolla consists of the five petals that are separate from one another except for a slight fusion at the tips of two of them. Thse consist of a huge upper petal (termed a "banner" or "standard"), and two lateral petals ("wings") held closely together and concealing the two lower partly-fused lower ones (together comprising the "keel").  Narrow-leaved vetch. June 21, 2009. Marion County, Ohio. Note also at

the base

of the leaf there is

a dark semi-circular gland

from which an ant is feeding. That is an extrafloral nectary. It is

an accessory nectar-secreting structure that serves not to attract

pollinators as do typical nectaries, which are located in flowers.

Rather, these nectaries promote

visits by ants which (I presume, not knowing whether this particular

case has been studied scientifically) provide the plant with protection

from

herbivores. The relationship is a good example of a mutualistic

symbiosis.

Here's a

video...

Ants

visiting

extrafloral nectaries on narrow-leaved vetch.

June 21, 2009. Morral, Marion County, Ohio. Flower

longhorn beetles tussle on pasture rose

June

21-26, 2009

Killdeer

Plains Wildlife Area, Wyandot County, Ohio

Longhorn beetles (Coleptera; Cerambycidea) are distinguished by having antennae that are as least half as long as, and often nearly as long as, their body. Members of this large family are all plant feeders. Longhorn larvae feast on the solid tissues of plants. Accordingly, they cause serious defects in lumber. Some kill trees; the notorious Asian longhorn for example, is threatening forests in the eastern U.S. and adjacent Canada. However, most contribute beneficially to forest ecology by enhancing the decomposition (recycling) of dead and dying trees. As adults, some species eat nothing, but many feed on flowers, in some cases with great specificity as to species of flower. Thus the family is the most effective of all beetle pollinators. Along the road separating Marion and Wyandot counties in north-central Ohio, pasture rose (Rosa carolina, family Rosaceae) is flowering now, and the longhorns seem to love it.  Pasture rose and flower longhorn. June 21, 2009. Wyandot County, Ohio. The beetles

visiting

the rose, munching its pollen and probably also sipping its

nectar

(do roses offer a nectar reward?), are "flower longhorns," i.e.,

members of the subfamily

Lepturinae, that Richard E. White in the Peterson "Beetles"

field guide

points out are often distinguished by having a bell-shaped (narrower at

the front) pronotum.

(He kindly explains that the pronotum is the upper part of the first

thoracic segment, a

segment that, in beetles, is generally prominent, so

that it

may

appear to comprise the entire thorax.)

A flower longhorn beetle (Strangalia luteicornis) displays bell-shaped pronotum. June 21, 2009. Wyandot County, Ohio. Thanks to a

pair of

terrific on-line resources --the BugGuide

and the wonderful accurately labeled photos of Tom

Murray on PBase --I was able to pin names on this

species (Strangalia luteicornis) as well as another

one, the "banded flower longhorn," Typocerus velutinus,

that seems to be competing quite successfully for space on the rose

blossoms.

While Typocerus velutinus stands prominently on a rose flower, Strangalia luteicornis peeking from beneath, considers making an ascent. A smaller beetle seems to be saying "I'm getting the heck out of here"! While is may

seem in

the photo below that the beetles are merrily

having lunch together, it might be more of an armed stand-off. The

larger Typocerus persistently

drives the smaller Strangalia off the flower,

but Srangalia keeps coming back, and even

aggressively tries to "jump" the big brute!

Two flower longhorn species on rose flower. June 26, 2009. Wyandot County, Ohio. Here's a

video showing

the

interaction between these flower longhorns.

Flower

longhorns tussle on rose flower. June 25, 2009. Wyandot County,

Ohio.

Ditdit-dit-ditditdit-dit-ditdit...News

flash!!!

Another

sanicle --S. trifoliata!!!

[dateline:

near Highbanks Metro Park, July 17, 2009]

While merrily snapping some pics of goldenseal fruits (coming soon), it was a pleasure to almost step on ...yay!!...another sanicle!!!  Large-fruited

snakeroot. July 17, 2009. Delaware County, Ohio.

As mentioned in the

sanicle/snakeroot essay

below, all

4 Ohio species of Sanicula

(family Apiaceae) look quite alike. But this plant immediately

stood out by virture of its young fruits being elliptical rather than

globose, and the hypanthium bristles seeming straighter (less hooked)

than the others. Back in the lab, reference to The Dicotyledoneae

of Ohio, Part 2 (Cooperrider, 1995) showed that a short-styles

Sanicula

with its comparatively few staminate flowers on relatively long

pedicles, bearing elliptical fruits that are sessile with a persistent

calyx that forms a persistent hard tuft at the fruit apex is

"large-ftuited snakeroot," S. trifoliata. The

species is found throughout Ohio. Below, a studio portrait displaying

those traits.  Sanicula trifoliata umbel. July 17, 2009. Note the persistent calyx forming a hard tuft. A tale of

two sanicles

Sanicula

gregaria and S. canadensis

June 19,

2009. Morral, Marion County, Ohio

The sanicles (also called "snakeroot," along with, it seems, about eleventy-seven other plants) are members of the genus Sanicula, in the wonderfully distinctive parsely family, Apiaceae. There are five Sanicula species in North America, four of which occur in Ohio. They tend to look alike. H. A. Gleason, in the best book ever written --The New Britton and Brown Ilustrated Flora of the Northeastern United States and Adjacent Canada (published in 1952 by the New York Botanical Garden) --explained "Our species are all glabrous and sparingly branched, 3-8 dm tall or rarely taller, and so alike in general habit that the existence of more than two species in our range was scarcely suspected until 1895." It's nice to be in good company, even if, as is most likely the case, the two species growing side-by-side at the Marion County Park District's Myer's Woods Preserve in Morral, Ohio are, by sanicle standards, the easiest to separate. By far the most abundant one here is "clustered snakeroot," Sanicula gregaria, widespread in the woods where it is shady.  Clustered snakeroot. June 14, 2009. Myer's Woods, Marion County, Ohio. At the edge

of the

woods there is a sanicle (snakeroot, whatever) that looks a little

different --the branches are more ascending than wide-spreading, and

the flower clusters also seem a bit more compact. Moreover, they appear

to be a little earlier along, phenologically, as some of the flowers

still have petals. Subsequent study revealed this to be "short-styled

snakeroot," S. canadensis.

Short-styled snakeroot. June 19, 2009. Marion County, Ohio. Both Sanicula species display a leaf feature typical of the Apiaceae --deeply cleft leaves with an expanded base. (The leaf base wraps around the stem a bit, although that trait isn't evident here.)  Short-styled snakeroot leaf. Marion County, Ohio. June 19, 2009. The hallmark

of the

Apiaceae, indeed why hence it is sometimes called the "Umbelliferae,"

is that the

inflorescence (flower cluster), is an umbel. An

umbel has all its flowers

attached at the same spot on the top of the flowering stem ("peduncle")

AND the flowers are individually stalked

(otherwise the inflorescence would be a head, not an umbel). A

signature example of an umbel (a

compound umbel, actually) is borne by Queen Anne's-lace (wild carrot).

At first

glance, snakeroot (sanicle, whatever) doesn't seem to have an umbel,

but

closer inspection reveals that it does.

Below, side-by-side, are the dense head-like simple umbels of our two most common species of sanicle (snakeroot, whatever). The genus displays another pecilarity: the flowers are of two types! Each umbel is composed of 3 sessile or (in this case) very short-pediceled "perfect" (hermaphroditic) flowers each with a bristly hypanthium covering the swollen inferior ovary, and mixed in are several-many staminate (male) flowers with smooth hypanthium, all or chiefly on long pedicels.  Fruiting umbels of sympatric Sanicula species. June 19, 2009. Marion County, Ohio. Left: S. gregaria. Right: S. canadensis. Diagnostic

features are

seen on both types of flowers. When the perfect

flowers of S. gregaria develop into

fruit, the two styles are longer than the bristles of the fruit,

recurved-spreading and conspicuous, whereas those of the aptly

(common) named S. canadensis --"short-styled

snakeroot" --are so short they just seem lost among all those

bristles. Meanwhile the staminate flowers of S.

gregaria are abundant --10-20 in number, and their sepals (calyx

lobes) have a broad triangular shape. Contrast these guys with the male

flowers of S. canadensis, which are much fewer in

number (only 1-5),

and have narrowly awl-shaped calyx lobes.

Below, an photographic explication of the diagnostic features of the two snakeicle (sanroot, whatever) species. First, see the style length feature that is evident on the perfect flowers. Then,

please MOUSEOVER

the IMAGE to see staminate flower

traits.

Distinguishing

features of co-occurring Sanicula species. Marion

County, Ohio.

Hello,

911? I'd like to report a

robbery!

Carpenter

bee on foxglove beard-tongue.

June 19,

2009. Marion, Ohio.

Is this

really an

emergency? I don't think so! Anyhow, flowers are exquisitely

constructed to maneuver visiting insects in a manner that fosters the

removal and deposition of pollen. However, some nectar-feeding insects

find it easier to circumvent the flower's design. Each June, a stand of

foxglove beard-tongue (Penstemon digitalis, family

Scrophulariaceae) at the Larry R. Yoder Prairie at the OSU-Marion

campus is visited by carpenter bees, honeybees, and

bumblebees. They tend to behave differently with respect to how they

exploit the flowers. Most strikingly, the carpenter bees totally

short-circuit the flower's "plan" by piercing a slit at the base of the

corolla and drinking nectar directly through it, with no apparent

benefit to the

plant.

Carpenter bee robbing nectar at Larry R. Yoder Prairie. June 19, 2009. Here are 820

more

pictures of

this, displayed successively, 1/30 second per

picture. Each

photo is slightly different than the previous one, and they seem to

blend together.

Carpenter

bee robbing

nectar from Penstemon digitalis. June 29, 2009.

Like looters

entering a

store after

somebody else has initially broken into it, honeybees acts as

"secondary theives," drinking nectar through slits made by the

carpenter bees.

Honeybee driking nectar through slits cut by carpenter bee. June 19, 2009. Marion, Ohio. Playing "Gallant" to Carpenter Bee's "Goofus," most (but not all) of the time the bumblebees are doing the right thing, entering the flower through its throat, thereby potentially effecting pollination. Bumblebee "legitimately" forages on foxglove beardtongue in Marion, Ohio. |