|

|

Welcome

to bobklips.com, the website of Bob Klips, a plant enthusiast living in

Columbus, Ohio. There's no trillium like snow trillium! ...and coltsfoot, (not) far far away! Delaware County, Ohio. March 31, 2009. In this Sunday's

Columbus Dispatch there

was a delightful article by naturalist John Switzer describing an

outing he had recently taken with a friend to see a rare species of

early-blooming trillium that, he explained, was actually first

discovered nearby, in 1834. Hopefully the newspaper people won't mind

if a faithful subscriber posts the article, demonstrating

the good

work they do promoting local natural history.

Columbus Dispatch

article on snow trillium. March 29, 2009.

By luck, a friend of

mine who is a friend

of the friend that John went on his outing with went on a similar

outing with him (John's friend) this morning and thus was able to give

me directions to the site.

The tiny blossom of a

snow trillium pokes through the leaf

clutter on the 11th

day of Spring in Delaware County.

Nearby, on a disturbed bank at the edge of the woods where the trillium is blooming, a intriguing alien wildflower is up. This is coltsfoot (Tussilago farfara, family Asteraceae). Coltsfoot is a perennial from a creeping rhizome. Its scaly-bracted but otherwise leafless flowering stems emerge before the leaves do.  In about a month

coltsfoot fruiting heads

will appear, dandelion-like but so intensely white they could be

mistaken for blossoms when seen along a road. The leaves will be

heart-shaped with angular lobes, resembling colt's feet. Coltsfoot is a

well-established herbal remedy for cough and sore throat.

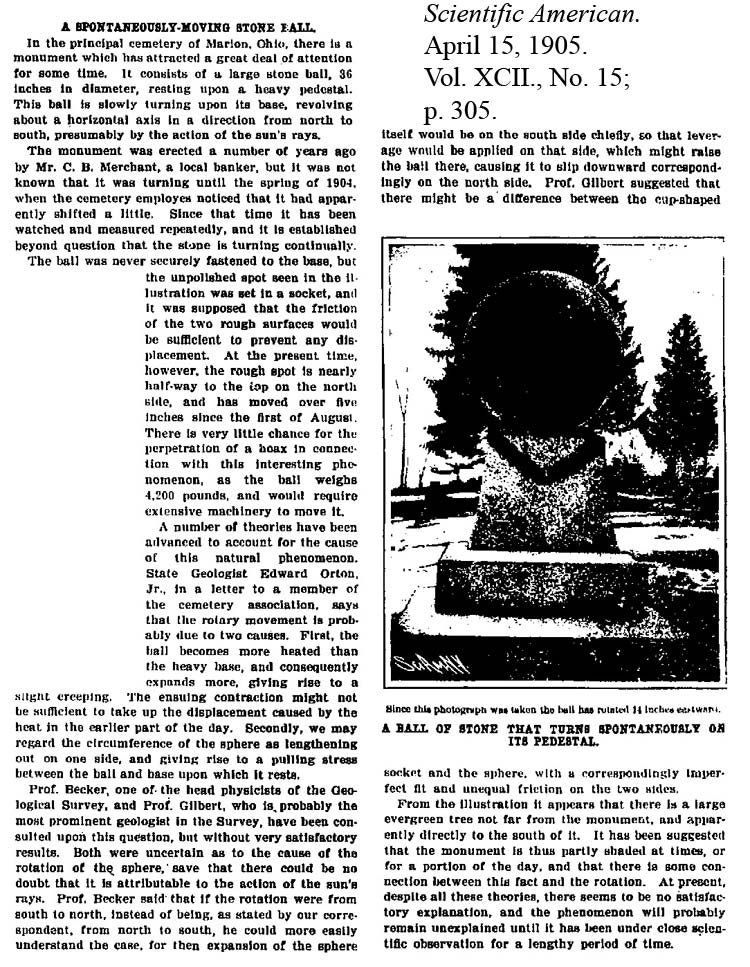

Silver Maple A Spontaneously Moving Ball Marion Ohio. March 31, 2009 Two weeks ago, the

silver maple (Acer saccharinum,

family Aceraceae) trees in the Marion Cemetery had just begun

flowering. Now, the clusters of female flowers are further developed.

This majestic tree in an older section of the cemetery displays them

well. Note for a moment though, another noteworthy object: the

spherical item seen between the lower two branchlets is one of the

wonders of the modern world: Marion Cemetery's famous Spontaneously

Moving Ball!

Silver maple branch with

late-stage female flowers. March 31, 2009.  Note amazing granite ball on pedestal in the background.  The light unpolished spot on the ball rested on the pedestal when it was constructed in 1896. The ball is made of

granite that was

polished after it was placed on the pedestal. Given that it weighs

approx. 5000 lbs., it was anticipated that it would not need

any

anchoring. But a few years after its construction in 1896, it

was

noticed that the rough spot that started out lowermost (and thus not

polished) had moved somewhat and by 1905 has shifted about 1/2 way to

the top. At that time it was the subject of a Scientific American

article.

Another Lichen (and another lichen

book)  April, 1905

Scientific American article about the ball.

Back to the maple. The pistillate silver maple flowers have begun to display an expanded ovary, with the expanded wings that later will enable their single-seeded fruits to be dispersed by the wind.  Silver maple

pistillate flowers. March 31, 2009.

Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio March 27, 2009 The slightly too weird

Photoshopped lichen face (scroll

down, at your own risk) apparently was unsettling to some people. Sorry

about that. But it doesn't take a whole lot of imagination, or having

recently seen Lord of the Rings: The Two Towers, to see lichen faces

even without digital image manipulation.

Foliose lichen Flavoparmelia

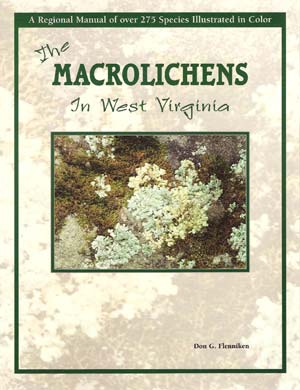

punctata on hardwood tree.

Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio. March 27, 2009. The identification of this lichen was made with the help of another excellent lichen identification manual, The Macrolichens in West Virginia, by Don. G. Flenniken. Like many manuals devoted to the biota of a particular region, it is almost equally useful in neighboring regions, in this case southern Ohio.  This book is great! Keys, descriptions and excellent photographs! Adorning the the wet sandstone cliffs of the Deep Woods Preserve is a lichen with such a peculiar green and fleshy aspect that it looks at first glance a little like a thallose liverwort.  Lichen-adorned wet rocks in mixed hemlock-haedwook forest. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County. March 27, 2009. Following the key, and noting that the thallus: (1) is not gelatinous; (2) is umbilicate rather than fruticose or podetiaform, and; (3) its surface has black dots (perithecia), revealed it to be a member of the genus Dermatocarpon, of which only two species occur in our area. This one --green when wet, light-colored beneath, and tending to occur on perennially wet sandstone --must be D. luridum.  Dermatocarpon

luridum. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio. March 17,

2009.

Nearby, on the same

sandstone ridge, an

interesting evergreen primitive vascular plant creeps

along. This

is the shining clubmoss Huperzia lucidula

(formerly Lycopodium lucidulum).

Shining clubmoss. Deep Woods Preserve. March 27, 2009. Looking closely, this

plant displays two

strikingly different modes of reproduction. In the axils of

many upper leaves there are small yellowish spore cases

(sporangia) in which single-celled spores were

formed by

meiosis. (The sporangia have split open, and are empty

now.) This

spore production is a sexual process equivalent to the production of

sperm and eggs by animals. Near the top of many stems,

asexually

produced plantlets called gemmae also occur.

Shining clubmoss displaying gemmae, and sporangia in the axils of the leaves. Deep Woods Preserve. March 27, 2009. Beautiful spring

wildflowers have begun blooming. One of them is American hazelnut (Corylus

americana,

family Corylaceae). Hazelnut has a pollination syndrome typical of

anemophilous (wind-pollinated) woody plants. The female flowers are

comparatively large, few in number, and topped with expanded

pollen-receiving stigmas. The male flowers are minute and aggregated

into drooping catkins that are well able to launch their pollen grains

into the breeze.

American hazelnut flowers. Left: two pistillate

(female) flowers. Right: staminate (male) catkins.  Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio. March 27, 2009. In early spring, while

it is sufficiently

warm but sunny because it is before leaf-out, wildfowers bloom in

midwestern deciduous

forests. Here is such a forest, at the Deep Woods Preserve in Hocking

County, taken from the Marathon pipeline right-of-way, facing south.

Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio. March 27, 2009. Two forest wildflowers.

Bloodroot (Sanguinaria canadensis, familly

Papaveraceae) is on the forest floor, while yellow harlequin (Corydalis

flavula, family Fumariaceae) is a rock-top plant.

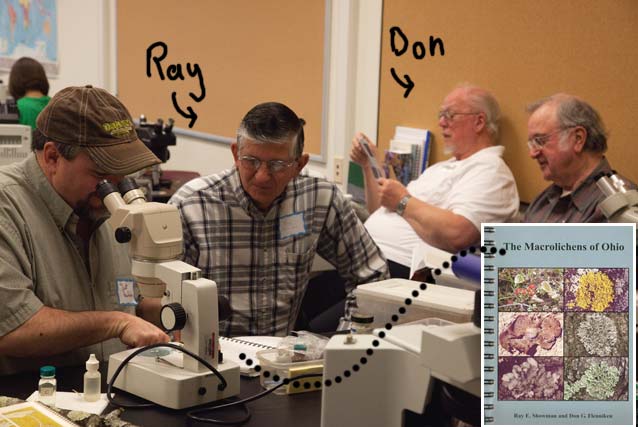

Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio. March 27, 2009. Lichen Caledonia, Marion County, Ohio March 22, 2009 A great thing about living in the Buckeye State is that there are many opportunities for enthusiasts with every style of interest to join like-minded people in the enjoyment of Ohio's biota. There are Ohio groups for beetles, lepidoptera, birds, native plants, and many other specialized taxa. Every year there are conferences and workshops such as the Ohio Botanical Conference and the Wildlife Diversity Conference. There are advanced naturalist workshops such as those held by the the Edge of Appalachia and Arc of Appalachia preserves. There are ongoing surveys such as the Ohio Spider Survey, periodic surveys like the Ohio Breeding Bird Atlas 2, plus occassional identification marathons such as the upcoming "bio-blitz" to be held in July at Old Woman's Creek State Nature Preserve. Arching over all of this is the venerable umbrella group, the Ohio Biological Survey, promoting natural history study in myriad ways, perhaps most notably by producing books and miscellaneous publications that guide the interested naturalist. One such citizen science group is OMLA: the Ohio Moss and Lichen Association. Mosses and lichens often grow together, and so the members of this terrific and friendly club like to prowl around together searching for the little "cryptogams." OMLA just held its annual meeting and workshop at the OSU Museum of Biological Diversity in Columbus. It was great fun and very educational.  Moss and lichen

enthusiasts at OMLA annual meeting and workshop. March 21, 2009.

Present were several lichen enthusisasts, and seeing them at work was inspiring. Two especially active OMLA lichenologists who were there are Ray Showman and Don Flenniken, the authors of a terrific lichen identification book "The Macrolichens of Ohio," published by the Ohio Biological Survey.  Lichen enthusiasts at

OMLA meeting, including the authors of The Macrolichens of

Ohio.

Most OMLA

members focus

much more on

one group, either bryophytes or lichens, but not

both. I'm a moss person for sure, but

maybe it's finally time

to learn a little lichenology. Lichens

are dual organisms consisting of a fungus and

an alga living in a close symbiotic relationship. Mostly though, a

lichen is a fungus, and lichen nomenclature (naming system)

and

distinctive

morphological features are fungal structures. Here's an unknown lichen

growing on a

piece of standing dead wood in an open disturbed area along a

road in

Marion, Ohio.

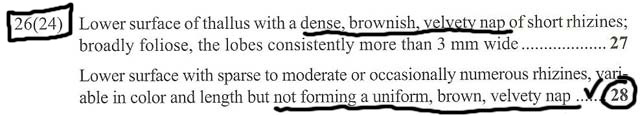

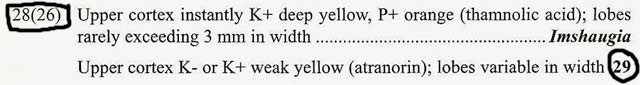

Standing woody debris with unknown lichen at Caledonia Preserve, Maron County, Ohio.March 22, 2009. The first couplet in

the key asks about

the general overall growth form of the lichen. The manual

explains there are several types of gross morphology,

including (1) crustose lichens that are crust-like,

very tightly appressesed forms that are not

considered "macrolichens" and so are not covered by the

manual;

(2) foliose lichens that are flattened, leaf-like,

with an upper surface that is diferent from the lower, and (3) fruticose

lichens consisting of upright branches that are round or flattened in

cross-section and, if flattened, have little difference betwen sides.

This one is obviously a foliose lichen.

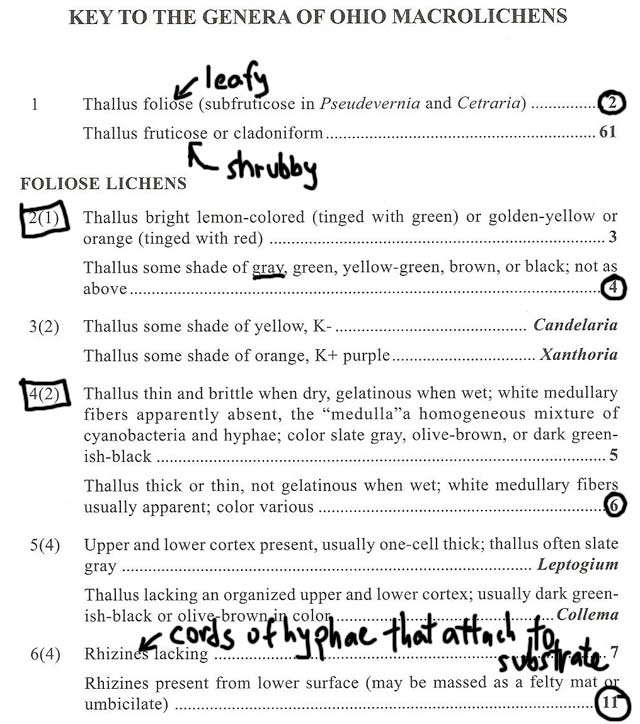

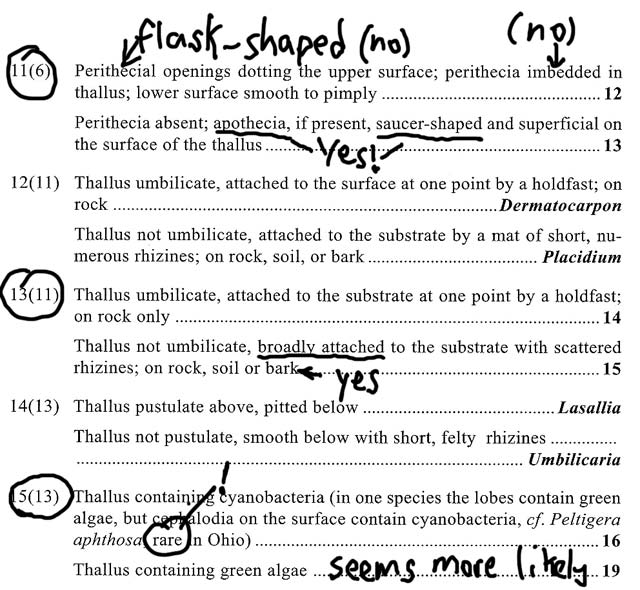

Lichen key in The Macrolichens of

Ohio. The apparently correct choices

("leads") are circled,  and the respective question pairs ("couplets") are indicated with a square. A closer view of the

unknown lichen shows it to be flattened and tightly adherent to the

tree bark.

Unknown lichen on woody debris at Caledonia Preserve, Maron County, Ohio. "Rhizines," the glossary tells us, are black to light brown, or translucent pale cords of hyphae (fungal threads) that project from the lower surface to the substrate and tend to anchor the thallus (plant body of the lichen). This will require examining the undersurface of the lichen.  Following the key some

more, we are asked what type of fungal spore-bearing structures are

present, more about the overall growth form, and about the

type of

algal partner; is it a cyanobacterium, or a green alga?

The fungal component of

a typical lichen is an ascomycete, i.e., a member of the huge class of

fungi that bear spores in microscopic tubular sacs called

"asci." While the asci themselves are too small to be seen with the

unaided eye,

they are packaged together in larger structures called "ascocarps" that

are distinctively shaped. The ascocarps that this lichen produces

are dish-shaped apothecia, not

flask-shaped "perithecia."

Upper surface of unknown lichen, showing the abundant dish-shaped apothecia and the absence of any perithecia. A cross-section of the

lichen shows the white interior (the medula), and a

layer of microscopic unicellular green algae

situated just beneath the upper surface layer (upper cortex).

Cross section of unknown

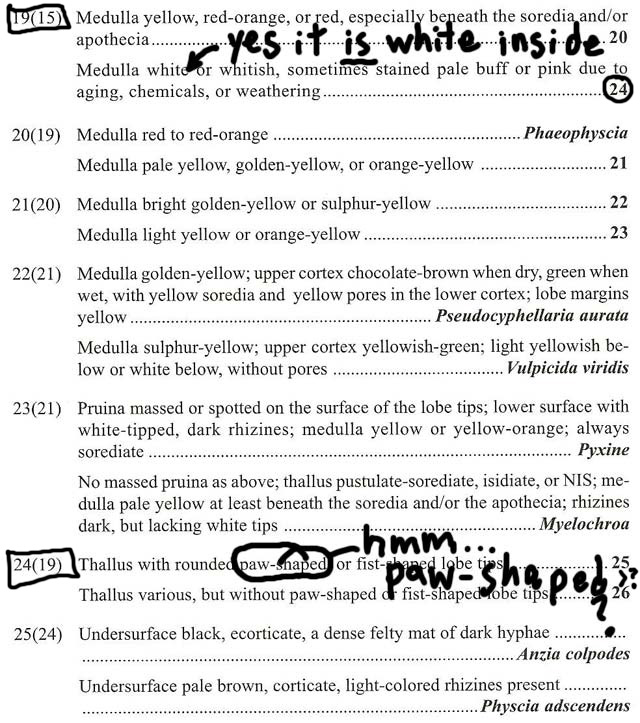

lichen showing green algae layer.  Getting back to the

key, we are asked about the color of the inside (the medula), and what

the margin of the thallus is like.

Are the lobes

paw-shaped? Hard to say. My brother and his wife in Brooklyn just sent

me a great

picture of their cat Lucky in his favorite sleeping box. Lucky has

paws.

How do they compare with the marginal lobes of the lichen? Let's

"pause" and take a look. (Bad pun I know, but at least be thankful

there are no "lichen/liking" ones!)

Lucky asleep,

oblivious to the comparison between his feet and the margin of

a lichen.

The lichen's marginal

lobes look somewhat paw-shaped, but maybe not paw-shaped enough. If

this one were paw-shaped, then it would be Physcia adscendens.

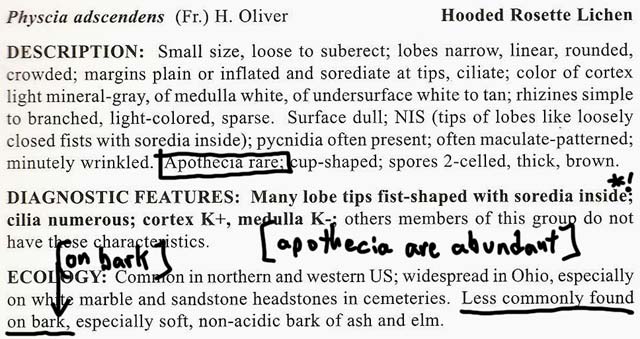

When starting out with a new group of organisms, it helps to

check species descriptions frequently for any gross

mis-matches. Ray and Don give useful DIAGNOSTIC FEATURES

for each species, and for the paw-lobed (hooded rosette) lichen, they

tell us some

things about its sporocarps and habitat that don't seem quite

right.

Maybe Lucky has

lichen-lobed feet! In any case, it's back to the key, where we are

queried about the undersurface of the lichen. Is there a velvety nap of

short rhizines?

Lucky seems to be taking

a nap,

but that's not any more relevant than his paws were! However, from the

image above of the lichen undersurface showing the sparse,

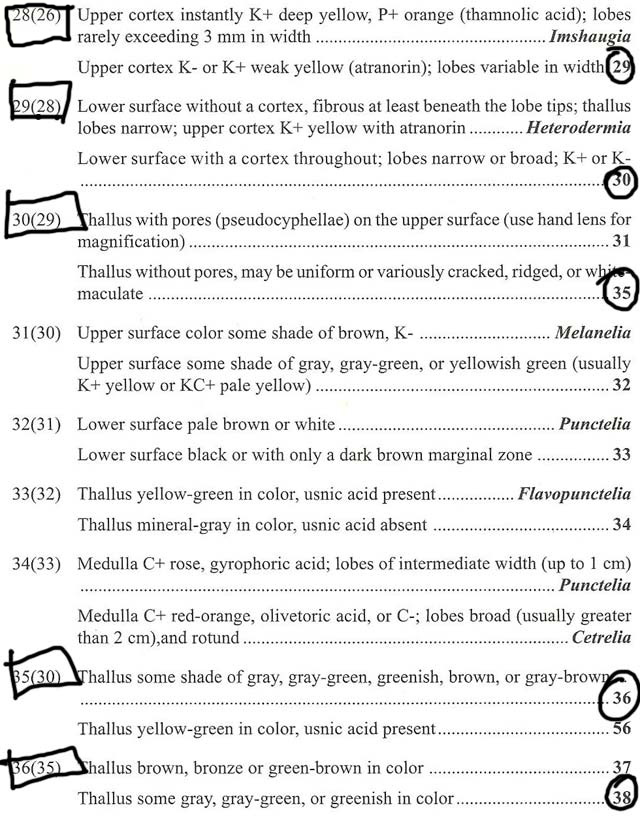

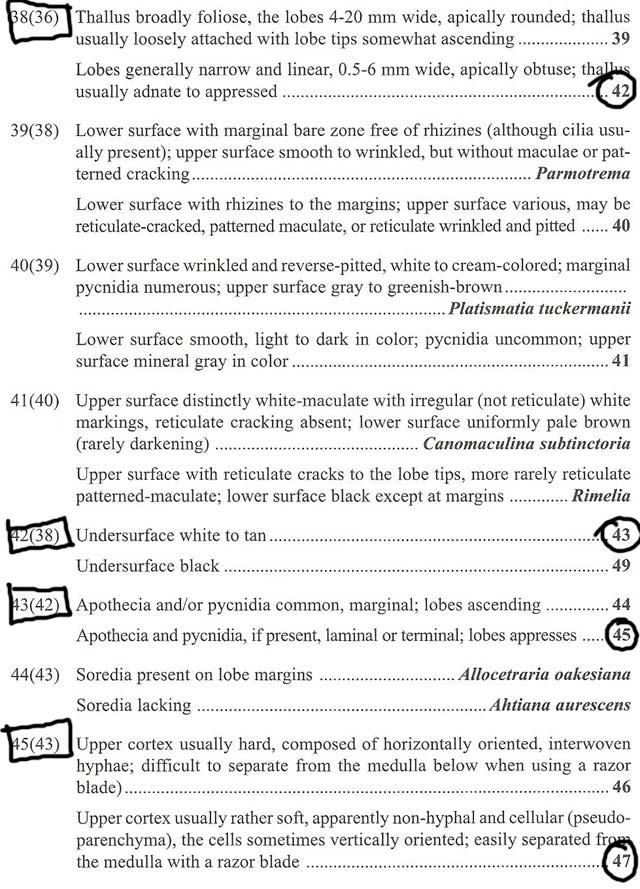

thick, light-colored rhizines, it's clear we need to go to couplet 28.

This is the first one that refers to a chemical test. Lichens tend to

contain secondary metabolites, usually complex organic acids, the

presence of which can be detected with spot tests,

and used as diagnostic features. There are 3 main

tests: the K test, utilizing 10% potassium

hydroxide (KOH); the C test, employing dilute

liquid bleach such as Chlorox, and; the P test,

performed with an exotic specialty reagent, paraphenylenediamine. This

couplet asks for the K test.

The image shows a cross-section of the thallus before and after applying a couple drops of KOH. We're keeping our eye out for a color change to yellow, noting how intense it is, how quickly the change occurs, and what part of the lichen it occurs on. MOUSEOVER the

IMAGE for K test results

There is certainly a color change to yellow, and it appears to be limited to the upper cortex. (The inner medulla stayed white.) It's a tough call, but apparently this color change is not as intense and immediate as it could be. This "weak" K+ reaction takes us to couplet 29.  ... more questions about color and details about size and shape.  ...and

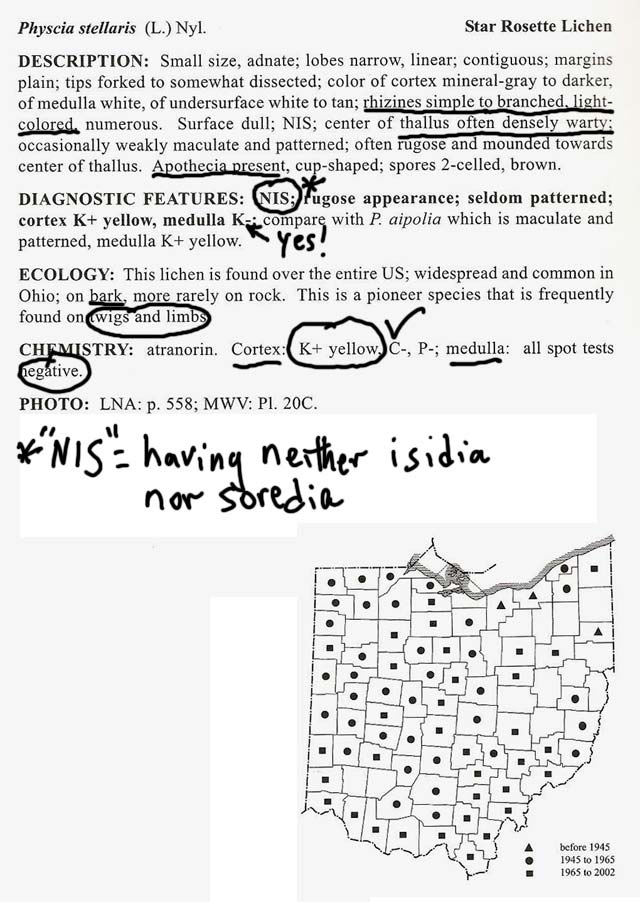

finally we come to a lichen genus, Physcia.

Ray and Don tell us

that Physcia is

"characterized by a medium sized thallus with linear to elongate lobes,

usually whitish-gray in color, upper cortex with atranorin (K+ yellow),

lower surface corticate, pale, with simple rhizines." There are 9

species in Ohio. The one this seems to be the star rosette

lichen, P. stellaris.

Yay!

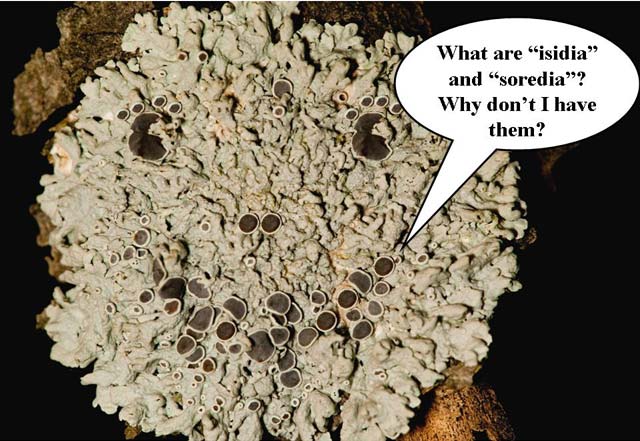

The lichen is unknown no longer! It is interesting that

this common foliose lichen produces neither isidia nor soredia.

And a pretty crude

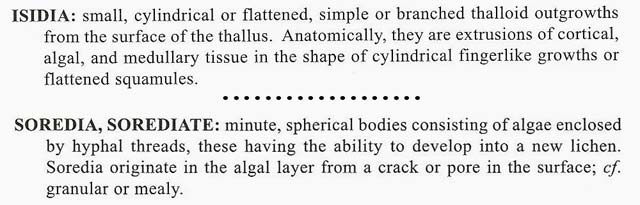

Photoshop job! An interesting aspect of lichen biology that we

chanced not to encounter while keying out Physcia

stellaris has to do with their

reproduction. Many foliose lichens produce specialized asexual

reproductive structures on their upper surface, of which there are two

types: fingerlike isidia and granular soredia.

They are well described in the glossary.

Isidia and soredia

defined in glossary of The Macrolichens of Ohio.

This raises two

questions. First, lacking

any obvious means to do so, how does this lichen reproduce? And

secondly, what's up with the apothecia? Why do lichenized

fungi

still produce them? The fungal spores alone are incapable of

perpetuating anything, so why haven't these structures gone out of

existence? Granted they might not be energetically costly to produce

and so natural selection might not strongly favor forms that lack them,

but there is an evolutionary mechanism akin to "use it or lose it"

whereby disruptive mutations will inevitably creep into the genome and,

without the purifying power of natural selection to retain needed

traits, un-needed ones will be lost. (As an example of this, we

primates have many messed up nonfuntional DNA sequences that match up

quite closely with olfactory receptor protein genes that are

fully intact and operational in other, less visually oriented, mammals

with which we share a common ancestor. These pseudogenes

(familiarly termed "fossil genes") are not very good evidence

for intelligent design.)

|