Fun with Apothecia!

Crustose Lichens at Eagle Hill Institute

Washington and Hancock Counties, Maine

June 29-July 4, 2015

It sounded intriguing, and it was: a week-long seminar workshop on crustose lichens at the Eagle Hill Institute in Steuben, Maine. Several of my OMLA (Ohio Moss and Lichen Association) friends who attended seminar workshops there in past years studying such arcane things as the difficult moss genera Bryum and Brachythecium came back raving about how wonderful Eagle Hill is. They were right! It’s a perfect mix of beautiful surroundings, rigorous study of fascinating little organisms, and very friendly, fun and considerate people.

Crustose lichens are one of the 3 principal growth forms of lichens. Sometimes called “microlichens” to contrast them from the larger foliose and fruticose “macrolichens,” crustose lichens are decidedly more challenging to identify. Hence the motivation for a 1000 mile road trip to learn from an expert, Dr. Irwin (Ernie) Brodo.

Below, see descriptions of the three lichen types, modeled after a page in the recently published Ohio Division of Wildlife “Common Lichens of Ohio” guide. Into the elegant lichen-sized empty spaces at the bottom of each column of text in the actual guide, I rashly pasted in illustrations of the three lichen types (crazy idea, I know), which were in fact drawn specifically for this guide by Katherine Beigel.

The first thing that caught my eye when I arrived at Eagle Hill was indeed a lichen, not a crustose lichen, but one of the least “micro” lichens you could possibly imagine. It’s Lobaria freaking pulmonaria!!! This is a big deal, or at least it would be if we weren’t in Maine. Ohio has old records from 14 scattered counties but no recent observations. It was included in the ODW lichen book as a “holy grail” lichen to look out for, and, because there are no known extant populations growing on buckeye trees (so to speak), the photo in the Ohio guide was contributed by a lichen enthusiast based in Maine (Ralph Pope), where it is apparently rather common, at least in moist mature forests.

Monday a.m. we went on a field trip to Black Mountain. Having heard about Black Mountain from the great American blues singer Bessie Smith, I was expecting to have a child spit in my face, while babies cried out for whiskey and all the birds sang bass. But it was nothing like that. Everyone was quite pleasant, and the birds were their usual chirpy selves. We stopped on the way to examine a peculiarly pink patch of ground.

Once we were in the pink, we learned why it was pink. Dibaeis baeomyces is a confused lichen that can’t decide whether it’s crustose or fruticose. The lower portion is a whitish crust, from which arise lollipop-like extensions capped by bright pink nearly globose apothecia.

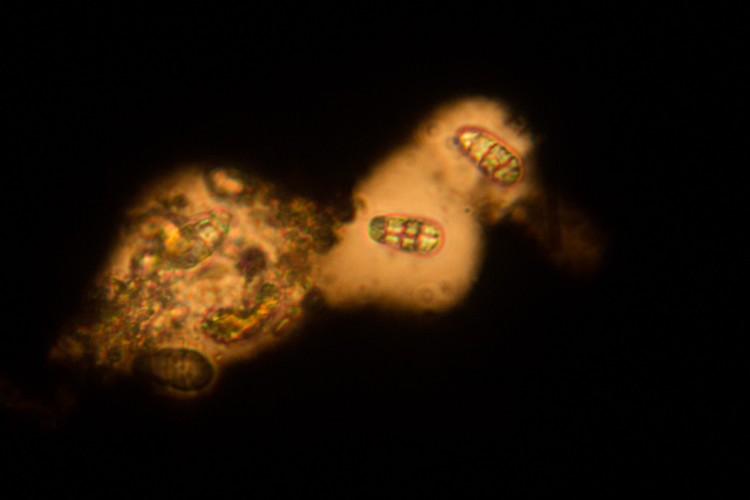

There were cobble-sized rocks on the ground amongst the Dibaeis, many of which were occupied by crustose lichens. Rhizocarpon is a common crustose genus with a well-developed areolate thallus. Several gray species occur on rocks.

Here’s a more closeup view. The black apothecia are of the “lecideine” type, i.e., having a black carbonized margin lacking algae.

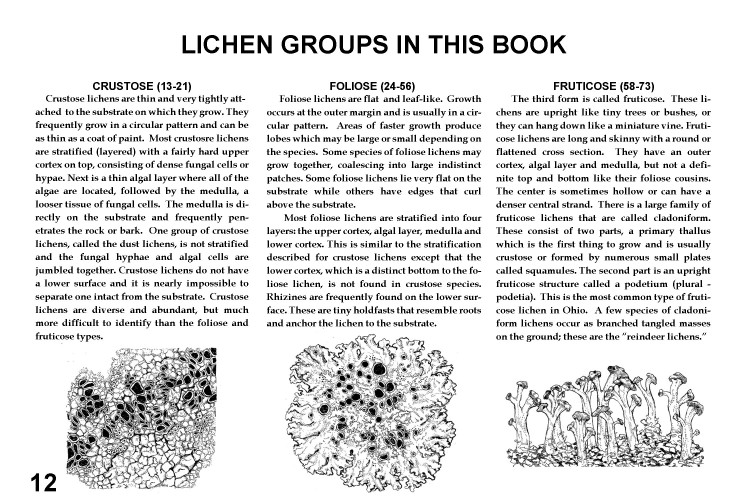

While a few other genera of gray areolate crusts are sometimes found on rock, a distinguishing feature of Rhizocarpon is that the spores are in most instances muriform, i.e., several-many celled with septa running both lengthwise and across each spore. Moreover, Rhizocarpon spores are “halonate,” surrounded by a gelatinous sheath that can only be visualized by adding a drop of India ink to the microscope slide, and noting a clear zone around each spore where the ink particles don’t penetrate. Based on spore size (small) and a few other features, I’m guessing this is R. reductum (formerly R. obscuratum).

We stopped at a moist woods where we began searching for different things on different types of bark. The base of a northern white cedar (Thuja occidentalis) was the best place to see a greenish granular crustose lichen with abundant apothecia. It’s Bacidia schweinitzii.

Closeup, we see the thallus is almost isidiate and the apothecia are black. Bacidia schweinitzii is “surprise lichen,” for strikingly contrasting colors that show when the apothecia are seen in section, magnified.

We paused for lunch and a group picture.

Then we headed up the mountain, exploring a lot of rocks along the way.

One of the rocks had a special lichen on it. This is coral saucer lichen, Ocrolechia yasudae. It’s one of only a few isidiate saxicolous crustose lichens. The apothecia, which are rarely produced, have a very bumpy rim.

Near the Ocrolechia on the boulder was brown-beret lichen, Baeomyces rufus. It’s a Dibaeis-like thing in that it has a crustose primary thallus from which project stalks bearing terminal apothecia.

At the bases of many spruce tree bases in this shady woods was a sterile crust, Loxospora elatina, a somewhat restricted species distribution-wise, distinguishable from the similar, more widespread L. pustulata by being genuinely sorediate.

Here’s a closeup showing the soredia of Loxospora elatina.

There are a great many granitic boulders in these woods. Many are luxuriantly covered with a brownish gray crust that we all tried to collect, substrate included, as our first chiseling exercise. It isn’t easy. All I managed to do was snowplow off a patch of it. We need a bigger hammer! Fortunately Dr. Brodo successfully chipped off a sample for each of us bad chiselers.

Lichens are sometimes pretty when wet. I was told that wet lichen photos aren’t very useful for identification, because specimens are generally dry. Oh well.

This is the sample I brought back to the lab, by then nice and dry.

This is the view from the mountain where you can’t keep a man in jail because if the jury finds him guilty the judge will throw his bail. I hate when that happens.

The flower of the week was sheep laurel, Kalmia angustifolia.

Yellow map lichen, Rhizopcarpon geographicum, is an exceptionally wide-ranging species, being found at high elevations across northern North America and the western mountain ranges.

Back in the lab we learned how to do microscopic identification and thin-layer chromatography to ascertain which lichen substances were present in our specimen, which are important distinguishing traits for many species.

Tuesday we went to see riparian lichens at Sprague Falls.

This is a swiftly-flowing river with large siliceous boulders along the bank.

The rocks provided substrate for a variety of crustose lichens,

Both here in real life using verbal words and also in print in Lichens of North America under the description of rusty brook lichen, Ionaspis lacustris on p. 363, Ernie Brodo tells us that “Rusty orange patches on streamside rocks are almost always this lichen.” Elsewhere reference is made to other aquatic lichens likely to be seen with rusty brook lichen, one of which is Rhizocarpon lavatum. This photo shows a patch of the Ionaspis, and I suspect that the more extensive background species with the black apothecia is indeed Rhizocarpon lavatum.

Here’s a studio shot of a piece of the Ionaspis lacustris. The apothecia are sunken into the thallus –a condition called “cryptolecanorine” –and thus are rather inconspicuous.

After the falls, we looked especially for lichens on bark in an open mixed deciduous/conifer woods. But on the way to the trees, we encountered a boulder that was home to an unusually thick granular-appearing sterile crust, Ochrolechia androgyna.

Ochrolechia androgyna is a variable species, occurring on bark and wood more often than on rock. Up close, the thallus can be seen to bear patches of yellowish granular soredia.

About eye-level on the bark of an oak tree we saw a very white crust with many prominently-margined apothecia; it’s frosted rim-lichen, Lecanora caesiorubella. This is a wide-ranging, primarily tropical species with several varieties, one of which –that I am presuming this to be –subspecies caesiorubella, has a Great lakes-Appalachian distribution that seems to include this portion of Maine. Note how the apothecia are pruinose (frosted looking).

The place we stopped for lunch was a bay with a high bank occupied by many cottonwood trees.

Cottonwood bark is especially soft and alkaline and, having a different chemistry than the hard-barked and more acidic oaks, support some different lichens. One species we saw there is common button lichen, Buellia stillingiana. This is a very widespread species, found over the entire eastern half of the U.S. and adjacent Canada.

Back at Eagle Hill, one of the more spectacular non-lichens is mountain fern moss, Hylocomium splendens.

Thursday we went to a coastal location, Petit Manan National Wildlife Refuge. It was nice, even though, as you can see, the scenery was very drab and uninspiring.

The class investigated some rocks.

Although it is a foliose lichen and therefore a bit off topic, it was an especial thrill to see maritime sunburst lichen, Xanthoria parietina.

This is a wide-lobed species. Neither isidiate nor sorediate, it produces abundant apothecia.

Xanthoria parietina occurs on both coasts (but also more inland in the west). During an evening lecture on his lifetime of lichen exploration, Dr. Brodo recounted how some old (mid 19th and early 20th century) reports of this lichen from Ontario were until recently discounted as having probably been in error, owing both to it being far from its coastal “home” and also because of a lack of any recent observations. But surprisingly, in the past few years maritime sunburst lichen has turned up at several spots in southern Ontario, perhaps partly as a result of substrate enrichment (eutrophication) stemming from agricultural activities there. The details are set forth in Brodo, I.M., C. Lewis and B. Craig. 2007. Xanthoria parietina, a Coastal Lichen, Rediscovered in Ontario. Northeastern Naturalist 300-306. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4499917.

It’s not only Ontario that is suddenly playing host to Xanthoria parietina. Apparently every so often it’s observed growing on nursery trees even farther from the Atlantic coast, obviously as a “hitchhiker” from wherever the trees were raised. This happened on May 1, 2011, when my spider biologist friend Richard Bradley visited an art gallery on the Ohio Wesleyan University campus in Delaware, Ohio, and snapped this picture there of Xanthoria parietina on a newly-planted maple tree. Where did the tree come from, we wonder?

Another insanely colorful maritime rock lichen is ringed firedot lichen, Caloplaca verruculifera. Members of the genus Caloplaca often have color that is more orange than yellow in tone, a useful field mark to differentiate them from Candelariella and some other yellow lichens.

Another seaside specialist grows on driftwood!

It’s driftwood rim-lichen, Lecanora xylophila.

In addition to the unusual and restricted habitat, this member of an especially large and variable genus can be recognized by its striking red-brown apothecia.

Maybe, however, this lichen should be renamed “Lecanora fiberglassophila,” because there on the ground we found this remarkable piece of flotsam.

Here’s a closeup. If you look closely you can see the glass fibers.

Friday was “Let’s explore Eagle Hill” day. We followed a path, alongside of which stands what remains of a tree, just the trunk, totally decorticated.

Looking closely, there’s a fine stubble on this that by virtue of its having brown two-celled spores that are presented in a dry powdery Eraserhead-like mass formed by the disintegration of the asci (called a “mazaedium”), seems to be a stubble (pin) lichen in the genus Calicium. The photo below shows a hint of yellow pruinia at the base of the capitulum, a diagnostic feature of yellow collar stubble lichen, Calicium trabinellum. I’m not quite sure about this one. The spores seem the right size, but not “ornamented with ridges or warts” as they are supposed to be. Also the yellow color is very scanty. Some similar calicioid fungi are not lichenized, either.

On a rock ledge we saw what might look to the uninitiated like just some amorphous crud growing on moss. But in fact it is no such thing! It’s actually amorphous crud growing on liverwort, the leafy liverwort Barbilophosia attenuata, to be exact.

The lichen is Trapeliopsis granulosa. Both during his evening lecture and in Lichens of North America (p. 687) Dr. Brodo mentioned that because this species is an important colonizer of bare soil and charred wood, forest managers in Quebec have spread it over burned forest plots where fire has removed the litter from the forest floor. The reflective white thalli cool the soil, promoting moisture retention, and the lichen itself slows erosion.

We visited a stone ledge in the woods that, in places, seemed dusted with a grayish sulphur yellow powder.

This is sulphur dust lichen, Psilolechia lucida.

The species has a granular to leprose thallus. It is easiest to identify when it is fertile. The apothecia are yellow hemispheres that lack a discernible margin.

There’s a hardwood tree with a sterile crust on the trunk.

I hate to say it at the end of such a wonderful workshop, but one of the last crustose lichens we encountered left a bad taste in my mouth! Oh, could that have been due to picrolichenic acid perchance? This is bitter wart lichen, Pertusaria amara, seen below battling it out with some Parmelia. A taste-test for this lichen is to scrape off a little bundle of sordia, place on the tongue and wait a bit. Bitter, but not poisonous!

This seminar workshop was great fun, educational, and unique. I highly recommend Eagle Hill!

POSTSCRIPT

Vis-a-vis crustose lichens, two potentially discouraging things might actually balance one another out. Discouraging thing #1 is the fact there are so very insanely way too many crustose lichens to learn in one lifetime. Boo! But then there’s the other sad fact that, compared with Maine at least, Ohio has a rather depauperate assemblage of them. So there might be hope after all, for knowing the local ones at least. I vowed to give it a try here in the Buckeye State. My first local foray was to the limestone bluffs along the Scioto River in Columbus, where I saw some… amorphous blackish-brown crud growing on rock!

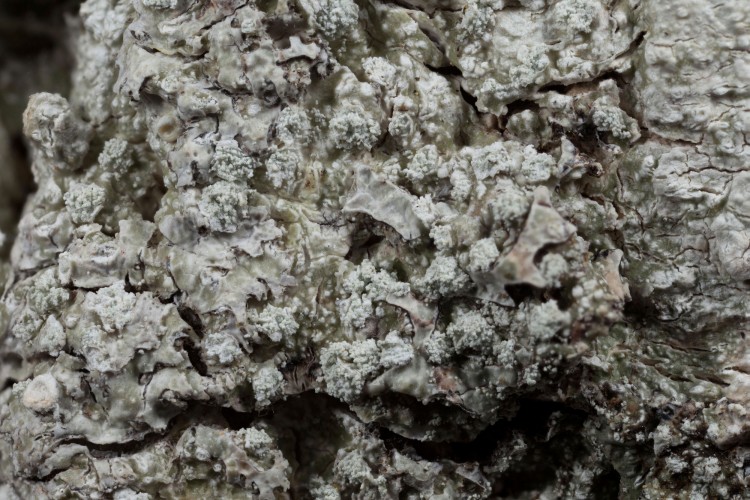

Oh come on, show some respect! Crud? This elegant and wonderful product of nearly 4 billion years of evolution is, apparently, ink lichen, Placynthium nigrum. I say “apparently” because, according to the keys and descriptions, this rather common limestone-loving crust has a cyanobacterial photobiont, but that really wasn’t evident through the microscope, hence keying it out wasn’t quite so straightforward. Also not clear yet is what a “prothallus” (conspicuous in this species) exactly should look like. Everything else fits though, and the peculiar color might indeed be a clue about the nature of the photosynthetic partner. Close up (the photo below was taken at 3x, then cropped a little) the brown irregularly cracked squamulose thallus contrasts nicely with the black apothecia. Pretty!