|

|

A

leafy liverwort and its gemmae. Diplophyllum apiculatum Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio. December 27, 2008 Along with the much more numerous mosses

and

the much less numerous hornworts, liverworts are a type of bryophyte.

Bryophytes are little plants that are usually described as

"non-vascular" because they lack the specialized plumbing

--water-carrying xylem and food-carrying phloem --that characterizes

all the other true plants. Compared to mosses, most

liverworts have more

intricate leaves, but by contrast the liverwort spore-producing stage

of the life cycle is simpler and more short-lived

than the corresponding sporophyte of mosses.

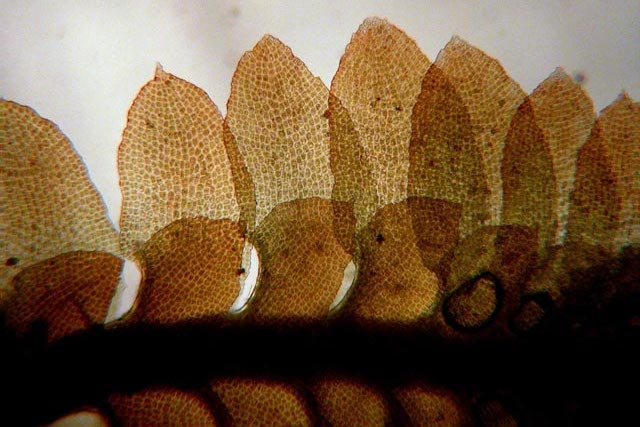

Mixed with mosses on a moist shaded sandstone ledge in a hardwood forest in southern Ohio is a lovely little leafy liverwort Diplophyllum apiculatum (family Scapaniaceae). Somewhat flattened, it has deeply two-lobed leaves that spread out in two rows on opposite sides of a horizontal stem, and these leaves are "conduplicate," i,.e, the rear edge is folded underneath and extends forward.  Diplophyllum apiculatum, approx. 25X microscope view (original).  Diplophyllum

apiculatum, approx. 40X microscope view (original)

Diplophyllum, like many plants, can

reproduce in two ways: (1) sexually through an intricate process

involving spores and eggs and sperm, and (2) asexually,

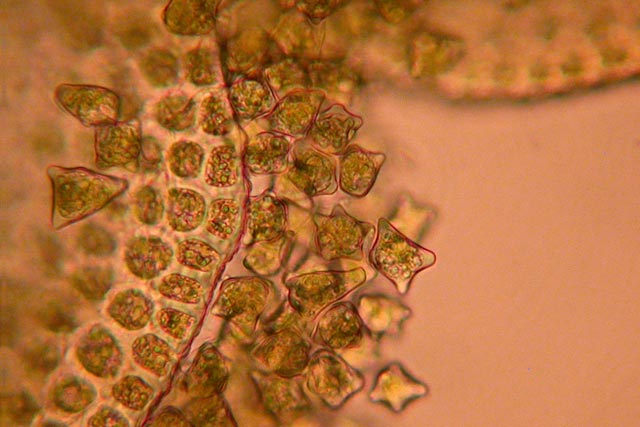

wherein a plant produces exact copies of itself. The asexual

reproductive structures of this liverwort are small 1-2 celled "gemmae"

produced abundantly at the tips of many branches. Diplophyllum

gemmae are

distinctively angular.

Diplophyllum apiculatum gemmae, approx. 400X microscope view (original) Air freshener is not very precise botanically! This air freshener says on it that

it's a "Royal Pine" freshener. But the conifer pictured on the package

has single (not bundled) needles. That feature, together with

the pendant (drooping) cones indicates the picture is actually a

spruce (genus Picea, family Pinaceae). Moreover, spruce

generally smells like cat urine, and pine is not a whole lot better,

being faintly turpentine-like. The best-smelling conifer is fir

(genus Abies, also in the Pinaceae).

Air freshener with an identity crisis! (Gas station shop in Marion, Ohio.) Butternut Walnut Hazelnut Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, OH December 27, 2008 Butternut (Juglans cinerea,

family Juglandaceae) is a beloved hardwood tree that is becoming scarce

throughout much of its range because of a fungus disease that causes

twig and stem cankers that eventually kill the tree. Sometimes called

"white walnut," butternut is a close relative of black walnut,

which is very common. In the winter, trees can be identified by their

twigs. Juglans twigs in general are distinctively stout,

with a prominent terminal bud and monkey-face leaf scars.

Twigs of two Juglans species. Left:

butternut (J. cinerea). Right: black walnut (J. nigra). How can you tell the two species apart by their twigs? Two main ways: (1) the terminal bud of butterut is proportionally longer than that of black walnut, and (2) the upper edge of the butternut leaf scar has a velvety moustache-like ridge that is lacking on black walnut.   Another intriguing Juglans twig

feature involves the pith (the softer cylinder in the center of the

twig,composed of a different cell type than the woody xylem that

comprises most of the twig). After making a longitudinal section

with a razor blade, you can see the pith is chambered, i.e.,

hollow with cross-partitions.

Contrary to what you might expect knowing that butternut wood is much lighter colored than black walnut, butternut pith is substantially darker!  Chambered pith of two Juglans species. Left: butternut (J. cinerea). Right: black walnut (J. nigra). Another woody plant that is distinctive in

the winter, if by chance it has some persistent fruits, is American

hazel (Corylus americana, family Corylaceae). The typically

paired nuts look like big-lipped talking heads facing away from each

other, maybe.

Fruits of American hazel. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, OH. Desember 27, 2008. Honey-locust et al. addition to "Dirty Trees" and Norway maple addition to "Tree Flowers"   Ephemeral Mosses (originally published in OBELISK, the newsletter of the Ohio Moss and Lichen Association ) www.ohiomosslichen.org Some of the most intriguing mosses are like pixies: small, cute, and appearing for a short time only. Ephemeral mosses tend to appear on disturbed open ground. Farm fields and moist spots in paths through open woods are good places to look for them. You need to get on your knees and keep the hand lens busy. Most or all of them are acrocarps, also called “cushion mosses,” i.e., mosses that consist of separate upright stems bearing sporophytes at their tips. In a manner analogous to the woodland spring wildflowers that burst forth during April before leaf-out shades them, ephemeral mosses generally occur when the potentially overtopping wildflowers or crop plants are absent. For

many species, their timing of occurrence is either

during spring or fall, but not both seasons. One of the most commonly

observed

species, somewhat larger than the other plants mentioned in this

article, is

the “urn moss,” Physcomitrium

pyriforme

(family Funariaceae). It is a spring ephemeral with distinctive broad

leaves

clustered at the base of the plant, and abundantly produced sporophytes

each

with a long seta (stalk) bearing a capsule shaped like a

child’s toy top. P. pyriforme

is known from 51 of

Interestingly, there is another plant, smaller but otherwise nearly identical in appearance that occurs in the same habitats (fallow fields, roadside ditches, etc.) as does Physcomitrium but it most often fruits in fall, and is only rarely seen in spring. This is Tortula (formerly Pottia) truncata (family Pottiaceae). While the Ohio Moss Atlas shows only five county records for this species, it is probably much more common, at least in regions with calcareous soils. The apparent rareness is probably an illusion due not to actual scarcity, but rather because naturalists don’t tend to crawl around on the ground as much in November as they do in May.  Pottia truncata. Marion County. November 5, 2007. Many ephemeral

mosses have sporophytes with setae that are

moderately or very short. Bruchia

flexuosa, (family Bruchiaceae) is an elegant spring-fruiting

species known

from 9 counties. The capsules, which are elevated slightly above the

linear

leaves, have a broadly tapered neck that contributes to an unusual

overall

shape reminiscent of a weather balloon. Like many ephemerals, Bruchia capsules

lack the lid-like operculum

that most mosses have, and thus the capsule ruptures irregularly to

release the

spores.

Bruchia flexuosa. Marion County. May 9, 2008 Several

other ephemeral mosses

have setae so short they are barely discernable, and so the capsules

are immersed in the uppermost leaves. One such species that is fairly

robust (for an ephemeral) grows in dense patches: Astomum

muhlenbergianum (family Pottiaceae). It is one of our few mosses with

involute (upward-curling) leaf margins. The species has been reported

from 12 Ohio counties.

Astomum muhlenbergianum. Marion County. March 27, 2008 A final example, among

the tiniest of the

tiny, is the aptly named genus Ephemerum (family Ephemeraceae), of

which E. crassinervium is our most common species. It occurs, spring or

fall, as scattered plants amidst a thin but sprawling alga-like growth

stage called the protonema, and is known from only 8 counties in the

State.

Ephemerum crassinerveum. Marion County. November 11, 2007. Some

other ephemeral genera to look for are Phascum

(Pottiaceae), Aphanorregma (Funariaceae), Pleuridium

(Ditricaceae), and Micromitrium

(a genus very similar to Ephemerum, also in the Ephemeraceae). The

“pixies” are fun to hunt, and seem to be a

strikingly

under-reported component of our moss flora. By looking closely at the

ground at odd times of the year in places which seem quite

unexceptional, it’s possible to meet some truly remarkable

plants.

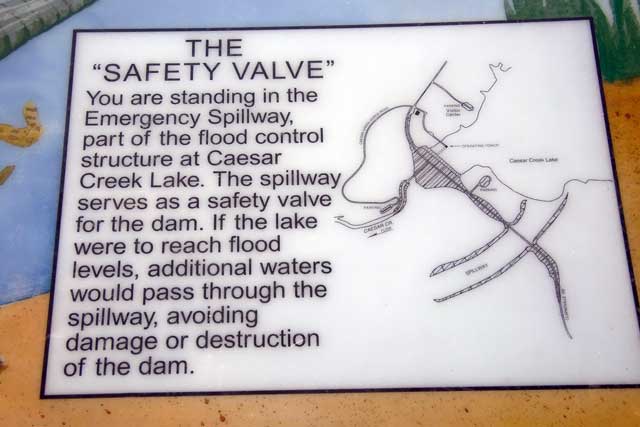

We took a trip to the sea, but we got there late! (400 million years late) Caesar Creek Lake State Park, Warren County, Ohio During the upper

Ordovician Period of the Paleozoic Era, southwestern Ohio was covered

by a shallow sea. Limestones and shales from this area and adjacent

portions of Indiana and Kentucky are extraordinarily rich in fossils.

One

of the best places to see them is at the spillway for the Caesar Creek

dam. During the late 1970's the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

built the dam to impound the nearly 3000-acre lake. They also excavated

a spillway to serve as a "safety valve" so that, in case there were

ever a severe flood that could potentially overtop the dam,

damaging the damn dam (sorry) in the process, the water would be

shunted around it. I'm not sure whether there's ever actually

been a

flood that high, unless you

accept creationist explanations for why we see the

remains of sea creatures in

places like this. Here's Google Maps view of the area (if it hasn't

shown up, "refresh" your browser):

("refresh" browser if the map

doesn't appear)

Aerial view of Caesar

Creek

Lake, dam and spillway.

(The spillway is at

the south, bisected

by Clarksville Road.)

The Corps

graciously allows fossil collecting here,

provided that you pick up a free permit and obey a few simple

rules. The area is marked by an interpretive sign.

Caesar Creek Lake spillway interpretive sign.  \ \Spillway detail, interpretive sign. The spillway is about

2700 feet long, 500

feet wide, and it exposes, in total, approximately 70 feet of shale

sedimentary rock strata. Fossils are likely to be found anywhere in the

spillway.

Spillway panorama, taken at west end, facing east-northeast. November 2, 2008. The early Paleozoic

was a time

when shelly marine creatures ruled the world. There are

representatives of the same phyla as contemporary animals, but

with strikingly different groups predominating. The most numerous

shells are those of brachiopods (lamp shells). Superficially, they

resemble clams

(phylum Mollusca) but internally they are very different animals.

Brachiopod fossils. Caesar Creek, Novemner 2, 2008. Although far less

common than the

brachiopods, there were indeed molluscs in the Ordovician. One group is

gastropods (snails). Here are two specimens.

Fossil gastropod molluscs at Caesar Creek. November 2, 2008. Another, more striking,

mollusc was the

cephalopod. This was a member of the same molluscan class as the squid

and octopus of today, but it had an external shell. It must have looked

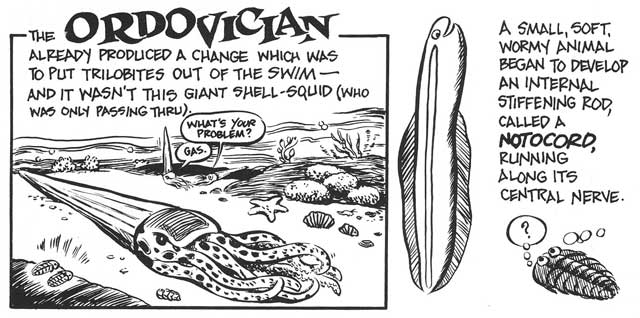

like an octopus with a dunce cap. In his masterpiece "The Cartoon

History of the Universe," imaginative cartoonist Larry Gonick

depicted a cephalopod, which he calls a "shell-squid" in the following

lighthearted manner.

Cephalopods were

chambered internally. This partioning is reflected in some of

the fossils, as shown below.

Fossil cephalopod mollusc, Caesar Creek. November 2, 2008. Corals belong to an

animal phylum that is

well represented both in the Paleozoic seas and the present day.

Along with jellyfish (nowadays more correctly termed "sea jellies"

because they are not fish), sea anenomes and hydra, these

animals are all predaceous carnivores who paralyze their prey using

tiny toxin-tipped stinging devices (cnidocytes). Coral animals are

individually small, and live in colonies within a stony (calcareous)

matrix

that they secrete. One of the most conspicuous and intriguing

Ordovician corals is the horn coral, belonging to an extinct order.

Horn coral fossils. Caesar Creek. November 2, 2008. An expecially common

organism back then,

similar to corals insofar as they are minute colonial animals that

construct limey apartment houses, were the bryozoans (phylum Bryozoa).

Bryozoans still exist today, but they are much less abundant now than

they were back then.

Fossil bryozoan. Caesar Creek. November 2, 2008. The phyum Echinodermata

includes starfish (nowadays

more correctly termed "sea stars" because they are not fish), sea

urchins (which are not urchins), sea lilies (which are

not lilies), and sea cucumbers (which, even though you can buy

them to eat

at the local Asian grocery store, are not cucumbers). Echinoderms

have spiny skin and, as adults, 5-part radial symmetry. Crinoids were

common in the Ordovician seas. Looking like flowers, a crinoids was

anatomically like a starfish on a stalk. Fossil-hunters are

rarely

lucky enough

to see the flowery tops, but screw-like crinoid stems are fairly

frequent.

Crinoid fossils at Caesar Creek. November 2, 2008. The Caesar Creek

Visitor's Center, where

you pick up the collecting permit, has a nice scientifically oriented

gift shop that sells nature guides and a "Fossils of Caesar Creek" T-shirt.

Happy fossil hunters at Caesar Creek. November 2, 2008. |