New Year’s Mosses Nashville (near Pigeye)

Miami County, Ohio

Who says that not much happens plant-wise during winter? Yes, the vascular plants are sleeping, but many mosses are merrily growing during the brief but frequent intervals of moist and above-freezing weather. Here’s a log in the woods carpeted by a very common, especially distinctive and beautiful moss. (Note: this is a natural log, using the base e, not some old common log to the base 10.)

Log substrate of fern moss. January 1, 2011. Near Pigeye, Miami County, Ohio.

Log substrate of fern moss. January 1, 2011. Near Pigeye, Miami County, Ohio.

The leaf is basswood; the moss is “fern moss,” Thuidium delicatulum. Note the moss’s light color, and its ferny twice-pinnate growth form.

Basswood leaf and fern moss near Pigeye, Ohio on New Year’s Day.

Basswood leaf and fern moss near Pigeye, Ohio on New Year’s Day.

Fern moss is found on a variety of substrates: soil, decayed logs and stumps, tree bases, generally in wet open areas. The genus name Thuidium is based on a supposed resemblance to the foliage of Thuja (northern white-cedar), and the specific epithet “delicatulum” means “very delicate.”

Thuidium delicatulum is twice-pinnate. January 1, 2011, near Pigeye, Ohio.

Thuidium delicatulum is twice-pinnate. January 1, 2011, near Pigeye, Ohio.

Tree bark is an important moss substrate. I think this is a buckeye, and the little green specks here and there are patches of a small cushion moss.

I think it’s a buckeye but I’m not sure.

I think it’s a buckeye but I’m not sure.

The moss is an Orthotrichum, probably O. pusillum. The genus is fairly easy to recognize, growing in small tufts, usually on trees, with immersed capsules and crowded ovate-lanceolate leaves that are not much contorted when dry (in contrast to Ulota crispa, a very similar contorted-leaved plant that also occurs high on bark). Species differentiation in this genus can be tricky, depending on some seemingly subjective features, such as by having (as in O. pusillum), an especially small and delicate capsule that is only lightly ribbed and not at all contracted below the mouth when dry. Note the capsules here are fairly well developed, but not yet mature. Spores will be shed in the spring.

Orthotrichum pusillum the morning after the ball dropped in Times Square.

Orthotrichum pusillum the morning after the ball dropped in Times Square.

Not American Chestnut (but a great conversation piece!)

December 7, 2010

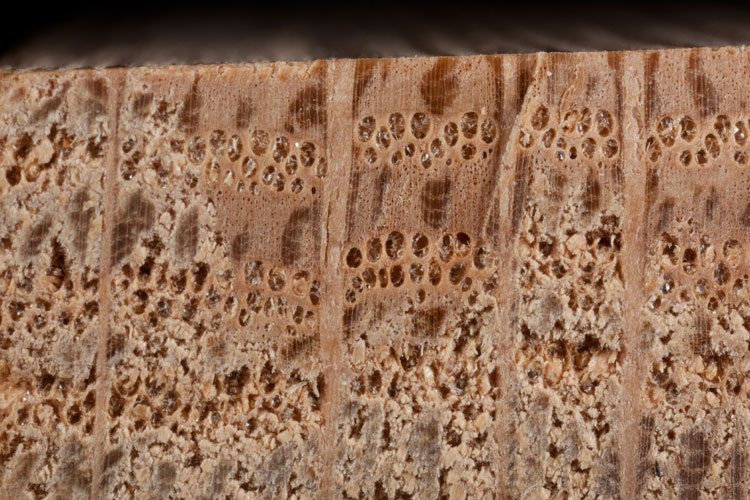

A friend thought perhaps a big old stump at the edge of a forest preserve in Crawford County was American chestnut, so he brought a chipped-out piece of the stump to be passed around and we all discussed it at the restaurant dinner table before this month’s “Science Cafe.” However, we weren’t stumped for very long; the wood was clearly not chestnut. It looked very much like the specimen shown below, taken from a sample set of common cabinet woods, and labelled as white oak. Oaks are ring-porous hardwoods, meaning that the water-carrying vessels produced in the spring of each year are larger in diameter than the later-formed summer vessels, and the distinction between the two size classes (earlywood and latewood) is quite abrupt. These tube-like vessels appear circular when viewed in cross-section, and hence are called “pores.” In this photo, the pores are oriented horizontally, showing 2+ complete years of growth. In the living tree, these pores are arranged in concentric circular rings. Running perpendicular to the growth rings, extending from the center of the tree to the circumference, are bands of a different type of tissue called rays. All trees produce narrow rays in their wood, but, uniquely, some of the the rays of all oaks are HUGE!!. The photo shows four of the gigantic rays that make this specimen, as well as the mystery chunk from the Crawford stump, a clear case of oak.

White oak is a ring-porous hardwood with very wide rays.

White oak is a ring-porous hardwood with very wide rays.

There are a great many oak species in the temperate forest, and therefore also in the lumber yard. Telling them apart can be difficult or unneccessary. However, the distinction between the two great oak sub-groups, white oaks and red oaks, is easy. Woods of the white oak group have their earlywood pores stuffed with what are called “tyloses,” i.e., they are filled with a transparent material that looks like some tiny person made tiny wads of tiny Saran wrap and puhed them it into the pores. Also, the latewood pores of the white oaks are so very small they are not individually discernable, looking instead like smoke billowing off the large earlywood pores. (The tyloses-stuffed earlywood pores renders white oak wood resistant to leakage, thus it has been used for barrels and casks for whiskey-making.) Red oak, by contrast, has open earlywood pores, and latewood pres that, while still abruply smaller than the earlywood ones, are individually distinct, and wider than the corresponding pores in white oak woods. You can blow air though a foot-long piece of red oak, making bubbles in a glass of water; it’s great fun!

Red oak is a ring-porous hardwood with very wide rays, and earlywood pores not stuffed.

Red oak is a ring-porous hardwood with very wide rays, and earlywood pores not stuffed.

What would chestnut have looked like? Simply this: like white oak, but lacking the huge rays. Here’s American chestnut from the wood sample set.

American chestnut wood: like white oak but without the rays.

American chestnut wood: like white oak but without the rays.

Cemetery Lichens Winter, 2010-2011

Marion County, Ohio

Humans obviously have a deep reverence for lichens. They have established special reserves for them, by installing large blocks of suitable lichen substrate in special areas kept clear of trees because sunny conditions are ideal for the lichens. As a supernatural tribute to the lichens, the remains of deceased humans have been placed under the lichen substrate-blocks. Here’s one such lichen park, Thew Cemetery in Caledonia, Marion County, Ohio. (Cemetery is an ancient Martian word that means “lichen haven.”)

Thew Lichen Preserve. Caledonia, Ohio.

Thew Lichen Preserve. Caledonia, Ohio.

Although lichens do commonly occur naturally on rocks on open areas, and many lichen species are indeed restricted to such sites, the lichen species commonly found in cemeteries are, surprisingly, not strictly saxicolous. Most cemetery lichens also do well on some of the soft-barked trees that grow in the vicinity. Cemeteries have a characteristic assemblage of lichen species, many of which are especially colorful. The yellows are refreshing at this bleak time of the year.

Lichens add color to the bleak winter landscape.

Lichens add color to the bleak winter landscape.

That brilliant lichen is Xanthomendoza fallax. Xanthomendoza (formerly a part of Xanthoria) is a genus of narrow-lobed foliose lichens unlike anything else in our area except the smaller, yellow-yellow not orange-yellow Candelaria, from which Xanthomendoza can also be distinguished by a simple chemical test. Xanthomendoza instantly turns dark purple when KOH is applied; Candelaria does not change color.

Xanthomendoza is a brilliant orange-yellow foliose lichen.

Xanthomendoza is a brilliant orange-yellow foliose lichen.

This was a rather severe winter, with long-standing patches and sheets of ice on the lichen substrate. Here’s Xanthomendoza with a partial canopy of ice in a shape that doesn’t look at all like a puppy dog.

Here’s a more uniform ice roof that looks like a miniature glacier.

Xanthomendoza during the Ice Age.

Xanthomendoza during the Ice Age.

Even through a mixed-up swirly ice lens, Xanthomendoza is dimly recognizable.

Xanthomendoza in the washing machine.

Xanthomendoza in the washing machine.

Xanthomendoza fallax isn’t the only brilliant lichen at this sanctuary. A crustose species, golden sunburst lichen, Candelariella aurella, also has quite a sunny disposition.

Candelariella aurella is a golden-yellow crustose lichen.

Candelariella aurella is a golden-yellow crustose lichen.

Occurring with the colorful yellow ones are several rather gray lichens. One of these is a type of “frost lichen” that I determined through a chemical “spot test” employing a mixture of equal parts 20% potassium hydroxide (KOH), bleach, and self-delusional uncertainty, to be Physconia leucoleiptes. This so-called “KC” test consisted of applying the bleach, quickly followed by KOH, on the powdery soralia along the thallus margin, and then observing a resultant faint color change to yellow. (Did I mention “faint”?)

Physconia leucoleiptes is a frost lichen.

Physconia can be recognized, at least to the genus level, by the combination of light gray above, black beneath, moderate-sized lobes, and, its most telling feature, a “pruinose” surface. This is a chalky whitish powdery bloom, the basis for the common name “frost lichen.”

Physconia has a pruinose surface.

Physconia has a pruinose surface.

Growing alongside the frost lichen on several of the substrate stones is a another gray foliose lichen, but one with a most distinctive morphology.

This is “hooded rosette lichen,” Physcia adscendens, which can be immediately recognized by its tubular paw-shaped lobes, often broken open at the tip, and with long cilia projecting from the upper margins of the lobes.

Hooded rosette lichen has paw-shaped lobes.

Hooded rosette lichen has paw-shaped lobes.

Hooded rosette lichen would be a bit difficult to recognize under thick ice, so it was nice to have a little “port hole” to see through.

Hooded rosette lichen under ice.

Hooded rosette lichen under ice.

Another medium-sized gray foliose lichen seen here at Lichen National Park bears abundant apothecia. (Apothecia are the spore producing structures characteristic of the fungus group most lichens belong to, the Ascomycota.)

A foliose lichen with abundant apothecia.

A foliose lichen with abundant apothecia.

Although it is formally known from just one Ohio county (Coshocton), this Physcia phaea is probably rather common on both natural rocks and lichen havens such as Thew. Its apparent rarity is a consequence of the fact that it was formerly lumped with a widespread very similar species, P. aipolia (hoary rosette lichen). The main difference is habitat, trees versus rocks.  Physcia phaea is a rock-dwelling rosette lichen. The surface of Physcia phaea (as well as P. aipolia and several others in that genus) is a bit frosty-looking too, but instead of it being pruinose like Physconia, it’s maculate, i.e., spotted and mottled due to gaps in the algal layer.

Physcia phaea is a rock-dwelling rosette lichen. The surface of Physcia phaea (as well as P. aipolia and several others in that genus) is a bit frosty-looking too, but instead of it being pruinose like Physconia, it’s maculate, i.e., spotted and mottled due to gaps in the algal layer.

Physcia phaea is maculate.

Here’s Physcia phaea and Physcia adscendens growing together under ice, including, on the left, a piece of ice that doesn’t look like anything like the head of a big-beaked bird.

A species of Physcia that is especially common on trees may be seen at these lichen sanctuaries, but, because it is so very narrow-lobed, can be discerned only if you look fairly closely.

This small gray foliose lichen is abundant but inconspicuous.

This small gray foliose lichen is abundant but inconspicuous.

It’s “mealy rosette lichen,” Physcia millegrana. Look for very narrow, finely dissected lobes broken into coarse soredia (asexual reproductive particles), along with abundant apothecia.

Mealy rosette lichen is narrow-lobed, with margins broken into a mass of soredia.

Mealy rosette lichen is narrow-lobed, with margins broken into a mass of soredia.

Yet another gray foliose lichen could easily escape notice not because it’s tiny (it isn’t) but because its color and texture match the substrate so well.

A large gray foliose lichen hides in plain sight.

A large gray foliose lichen hides in plain sight.

This is “bottlebrush shield lichen,” Parmelia sulcata, a very common species seen most often on trees. It is fairly wide-lobed, patterned-maculate above, with a coffee-black undersurface.

Bottlebrush shield lichen has patterened ridges on its lobes.

Bottlebrush shield lichen has patterened ridges on its lobes.

This patch of substrate has what looks like a patch of spilled paint on its upper edge.

An unusual lichen growth form: squamulose.

An unusual lichen growth form: squamulose.

Most lichens fall into one of three well-known catgories of growth form: fruticose (shrubby), foliose (leafy), and crustose (like a crust). However, there is another form called “squamulose,” that is more or less intermediate between foliose and crustose. “Squamules” are small scale-like lobes that lift from the surface, at least at the edges. “Golden moonglow lichen,” Dimelaena oreina, is a squamulose lichen found on sunny siliceous rocks.

Golden moonglow lichen is a greenish-yellow squamulose lichen.

Golden moonglow lichen is a greenish-yellow squamulose lichen.

Here’s Physcia adscendens, with a backdrop of a crustose or squamulose lichen that I haven’t been able to identify yet.  Hooded rosette lichen, and a dark, as-yet unknown lichen.

Hooded rosette lichen, and a dark, as-yet unknown lichen.

Little White Dots on a White Oak Stump

(Xylobolus frustulatus, a crust fungus)

Seymour Woods State Nature Preserve Delaware County. Ohio. November 21, 2010.

Seymour Woods State Nature Preserve is a lovely woodland preserve that doesn’t require a special access permit, so it’s a great place for a spur-of-the-moment visit on a Sunday afternoon. On the crest of a ravine near a moment-spur, there’s this stump of a white oak.

White oak stump at Seymour Woods. November 21, 2010.

White oak stump at Seymour Woods. November 21, 2010.

Stumps are substrate for a variety of interesting organisms, including of course fungi that are capable of digesting cellulose. (That is not an easy thing to do.) This stump has little white dots on it that seems to be some type of fungus.

Little white dots on a stump. November 21, 2010.

Little white dots on a stump. November 21, 2010.

Here’s a close-up of the little white dots. They look very distinctive, but what the heck are they ..and how the heck could you find out? They’re not mushrooms, so they’re not in the any of my mushroom books. I’m stumped!

Little white dots, close-up. November 21, 2010. Delaware County, Ohio.

Little white dots, close-up. November 21, 2010. Delaware County, Ohio.

Once upon a time, identifying something like this would have taken a whole lot of poking around a library to learn what university has a friendly mycologist who specializes in wood-decaying fungi, to whom you could send it in hopes of getting a nice letter back with the name of the thing. That’s so much more trouble than typing some free-association beat poetry into Google, and miraculously seeing this (link): Hooray for the interwebs!! (link to mushroomexpert.com) Fabulous fungus fan Michael Kuo tells us this is Xylobolus frustulatus, which he calls “a fascinating crust fungus that looks like whitish tile fragments put together carefully with black grout. He whimsically and aptly compares this fungus to cubist art, and explains that it is is common, and grows nearly exclusively on dry, well decayed wood of white oak. Here’s a closer-up photo of “Crusty,” looking indeed quite like an art project.

Xylobolus frustulatus is a fascinating crust fungus.

Xylobolus frustulatus is a fascinating crust fungus.

There’s another saprobic basidiomycete here in the woods.  Well-decayed log with a cluster of puffballs. November 21, 2010. Delaware County, Ohio. It’s one of the very few puffballs to occur on wood (as opposed to the ground), and a very common one: Morganella pyriformis, formerly known, and still widely referred to, as Lycoperdon pyriforme. The specific epithet means “pear-shaped.” With apologies to Peter, Puffball, and Mary (and most of all, to you)…here’s a pretty scary video.

Well-decayed log with a cluster of puffballs. November 21, 2010. Delaware County, Ohio. It’s one of the very few puffballs to occur on wood (as opposed to the ground), and a very common one: Morganella pyriformis, formerly known, and still widely referred to, as Lycoperdon pyriforme. The specific epithet means “pear-shaped.” With apologies to Peter, Puffball, and Mary (and most of all, to you)…here’s a pretty scary video.

Puff the Magic Puffball Lived on a Log.