(Additional content at flickr Photostream and YouTube Channel)

If you have botany questions or comments please email BobK . Thanks!

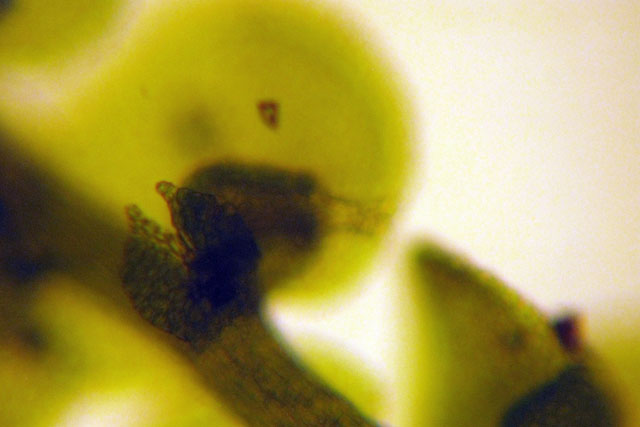

(Hysterium barrianum)

Morral, Marion County, Ohio March 31, 2010

I'm trying to

learn a bit about lichens. Goal: be able to name the very

common ones on sight, and gain sufficient facility to run an unknown

through the keys. It's great fun and is going quite well, thanks

mainly to gracious assistance provided by uber-friendly lichenologist

members of OMLA, the Ohio

Moss and Lichen Association. If you have an interest in lichens,

join the club!

A well-known distinction, and the starting point for lichen identification, is the overall growth form, of which there are three main types: fruticose, foliose, and crustose (i.e., shrubby, leafy, and crusty).

FRUTICOSE lichens are stalked, pendant, or shrubby, with no clearly distinguishable upper and lower surface. The quintessential fruticose lichens in Ohio belong to the genus Cladonia. Most Cladonia species begin development as a scaly (squamulose) primary thallus. ("Thallus" is the general term for a relatively featureless body, the kind had by a fungus, algae, or even some plants, wherein specialized intricate organs are lacking.) Later on, a hollow upright structure, the "podetium" develops. Podetia, depending upon the species, may be pointed, clubbed, or topped by cups and, depending on the species, may bear spore-producting apothecia.

Here are two cladonias seen recently. The first is "peg lichen," C. polycarpoides. This species has fairly long primary squamules that persist after the podetia have formed. Each podetium ends in a large brown apothecium. Peg lichen is common on soil in old fields and roadside banks.

Wand lichen, Cladonia rei, is a cup-forming fruticose lichen that produces apothecia at the tips of numerous proliferations of the cup margins, resembling a little star, giving the overall impression of a magic wand. The primary squamules (not visible in the photo below because it focuses on the upper parts) are small and sparse.

FOLIOSE lichens have a more or less "leafy" growth form, distinctly dorsiventral, and varying in the degree of attachement to the substrate, from completely adnate to only centrally attached (umbilicate). Foliose lichens seem to be especially common on tree trunks, comprising most of the ones on this hardwood at Dawes Arboretum in Licking County, Ohio.

Foliose lichens on brak (bark, whatever).

April 4, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

CRUSTOSE lichens are in contact with the substratum at all points and lack a lower tissue layer (the cortex) had by the other lichen types. Crustose lichens cannot be removed intact without removing a portion of the substrate as well. Here's the very unremoved substrate of a couple of crustose lichens noted recently at the OSU-Marion campus.

Concrete-based pipe thing where crustose lichens grow. Marion, Ohio. April 2, 2010.

Script lichen lookalike, Hysterium barrianum.

A well-known distinction, and the starting point for lichen identification, is the overall growth form, of which there are three main types: fruticose, foliose, and crustose (i.e., shrubby, leafy, and crusty).

FRUTICOSE lichens are stalked, pendant, or shrubby, with no clearly distinguishable upper and lower surface. The quintessential fruticose lichens in Ohio belong to the genus Cladonia. Most Cladonia species begin development as a scaly (squamulose) primary thallus. ("Thallus" is the general term for a relatively featureless body, the kind had by a fungus, algae, or even some plants, wherein specialized intricate organs are lacking.) Later on, a hollow upright structure, the "podetium" develops. Podetia, depending upon the species, may be pointed, clubbed, or topped by cups and, depending on the species, may bear spore-producting apothecia.

Here are two cladonias seen recently. The first is "peg lichen," C. polycarpoides. This species has fairly long primary squamules that persist after the podetia have formed. Each podetium ends in a large brown apothecium. Peg lichen is common on soil in old fields and roadside banks.

Peg lichen at OSU-Marion

Campus

Prairie. March 31, 2010

Wand lichen, Cladonia rei, is a cup-forming fruticose lichen that produces apothecia at the tips of numerous proliferations of the cup margins, resembling a little star, giving the overall impression of a magic wand. The primary squamules (not visible in the photo below because it focuses on the upper parts) are small and sparse.

Wand lichen at Dawes Arboretum.

April 4, 2010.

FOLIOSE lichens have a more or less "leafy" growth form, distinctly dorsiventral, and varying in the degree of attachement to the substrate, from completely adnate to only centrally attached (umbilicate). Foliose lichens seem to be especially common on tree trunks, comprising most of the ones on this hardwood at Dawes Arboretum in Licking County, Ohio.

Foliose lichens on brak (bark, whatever).

April 4, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

There are several species

here ...it's a vertiable lichen salad! The lowermost large one is

"powdered ruffle lichen," Parmotrema

hypotropum.

Some of the distinctive features of this lichen are its pale greenish

gray upper surface, an undersurface that is black with a broad pale

margin, the presence of long eyelash-like cilia on the margin, and,

also on the margin, localized regions called "soralia" where powdery

vegetative propagules called "soredia" are produced. Soralia can be

seen along the edge of the thallus in the lower right corner of the

picture.

Powered ruffle lichen on bark. April 4, 2010. Licking County Ohio.

Powered ruffle lichen on bark. April 4, 2010. Licking County Ohio.

CRUSTOSE lichens are in contact with the substratum at all points and lack a lower tissue layer (the cortex) had by the other lichen types. Crustose lichens cannot be removed intact without removing a portion of the substrate as well. Here's the very unremoved substrate of a couple of crustose lichens noted recently at the OSU-Marion campus.

Concrete-based pipe thing where crustose lichens grow. Marion, Ohio. April 2, 2010.

The

concrete is substrate for a

couple of crustose lichen species, one of which is dimly visible as a

yellow patch along the upper edge, seen close-up as presenting a great

many bright yellow cup-shaped spore-producing bodies (apothecia).

Before testing it with KOH, the best guesses for the yellow one were Candelariella, Candellaria, or Caloplaca.

After determining it is K- (no reaction), signs point to "hidden

goldspeck lichen," Candelariella

aurella,

said to be the most common of the goldspeck lichens on calcareous rock.

And that odd gray one in the lower left that I initially mistook for a

dead old yellow one (!) is a certain call.

That's "mortar rim-lichen," Lecanora

dispersa,

described by Brodo, et al.

in "Lichens of North America" as "a

survivor," ...going on to say "In New York City, it is the only one to

persist in central Brooklyn (on concrete fences in Prospect Park)."

They explain that the ability of this lichen to tolerate the urban

environment is attributable to the fact that it occupies a calcium-rich

substrate. This

buffers the effects of acid precipitation, often deadly to lichens.

Crustose lichens on concrete. April 2, 2010. Marion County, Ohio.

An odd little sub-group of crustose lichens are the "crustose script lichens." These produce specialized peculiar elongate, often carbon-black, apothecia termed "lirellae." Frequently found growing on bark (but some species dwell on rock), they can resemble writing in some cryptic Druid language. Here's a hickory tree growing at the edge of a woodland upon which is one of them, apparently made by a cryptic Druid with a messy handwriting, since it's called "scribble lichen." It's Opeographa varia.

Hickory tree substrate of scribble lichen.

March 31, 2010. Morral, Marion County, Ohio.

Crustose lichens on concrete. April 2, 2010. Marion County, Ohio.

An odd little sub-group of crustose lichens are the "crustose script lichens." These produce specialized peculiar elongate, often carbon-black, apothecia termed "lirellae." Frequently found growing on bark (but some species dwell on rock), they can resemble writing in some cryptic Druid language. Here's a hickory tree growing at the edge of a woodland upon which is one of them, apparently made by a cryptic Druid with a messy handwriting, since it's called "scribble lichen." It's Opeographa varia.

Hickory tree substrate of scribble lichen.

March 31, 2010. Morral, Marion County, Ohio.

The scribble lichen does

indeed resemble little random felt-tip marker markings on the bark. The

area

between the scribbles is occupied by a thin thallus that, when

scratched,

exposes green algal cells, constituting the only obvious evidence that

this is indeed a

lichen.

Scribble lichen on hickory bark.

There are some unlichenized fungi that, while

not closely related to the script lichens, constitute an interesting

example of convergent

evolution because they strongly resemble some script lichens. While

out lichen-hunting I found one of these script lichen lookalikes. It's

growing on this white oak in an open

woodland in Morral, Marion County, Ohio.

White oak substrate of possible Hysterium barrianum.

Morral, Marion County, Ohio.

Scribble lichen on hickory bark.

White oak substrate of possible Hysterium barrianum.

Morral, Marion County, Ohio.

Like most lichens it's an

ascomycete fungus. It's in the family Hysteriaceae, about

which there is a wealth of great information on this web site. Its

specialized ascoma, termed a "hysterothecium," is elevated

above the substate and opens by a narrow longitudinal slit along the

top. Based on spore dimensions (45 x 11 micrometers) and

morphology (inset; note 7 crosswise septa) this is be the recently

described Hysterium barrianum.

Script lichen lookalike, Hysterium barrianum.

Leprose lichen Lepraria lobificans loves limestone

like large leafy liverwort Lophocolea loves logs.

Delaware County, Ohio. March 21, 2010

In woods on the high east

bank of the Scioto River are outcroppings of Columbus Limestone of

Devonian age upon which grows an exceptional lichen.

Limestone home of the fluffy dust lichen. March .21, 2010

It's a one of a few genera of lichens that are "leprose," i.e. having a thallus (or at least a thallus surface) composed entirely of powdery soredia. Soredia are vegetative propagules consisting of a few algal cells entwined and surrounded by fungal filaments. This odd lichen lacks any well organized tissues --outer cortex and inner medula --had by many lichens. It's just undifferentiated fluff! Considered a crustose lichen because it is in contact with the substratum at all points and lacks a lower cortex, this is the most common of the well named "dust lichens" that constitute the genus Lepraria. It's fluffy dust lichen, Lepraria lobificans.

Fluffy dust lichen. March 21, 2010. Delaware County, Ohio.

Nearby, a community of mosses

and liverworts occupies a decorticated log.

Log habitat of mosses and liverworts. March 21, 2010.

Lophocolea heterophylla. March 21, 2010. Delaware County, Ohio.

Nearby, an American sycamore proclaims "Trespassing Violators will be Ted." That doesn't make any sense. Who's Ted?

Log habitat of mosses and liverworts. March 21, 2010.

One of them is Lophocolea heterophylla (family

Geocalycaceae), a fairly large by liverwort standards leafy liverwort,

the leaves of which overlap in a succubous manner, i.e., the forward

edge of each leaf is situated beneath the base of the leaf ahead of it.

Note near the center of the photo, a developing sporophyte. According

to the Liverwort

Tree of Life evidence is accumulating that

liverworts (Phylum Marchantiophyta) were the first land plants to

diversify on land some 500,000 million years ago and as such are the

oldest living lineage of land plants.

Lophocolea heterophylla. March 21, 2010. Delaware County, Ohio.

Nearby, an American sycamore proclaims "Trespassing Violators will be Ted." That doesn't make any sense. Who's Ted?

Sign-eating American Sycamore. March 21, 2010.

Wee White Wildflower

Trillium nivale

Delaware County, Ohio March 21, 2010

Snow trillium (Trillium nivale, Liliaceae, the lily family) is our smallest, earliest, and cutest trillium.

Snow Trillium. Delaware County, Ohio. March 21, 2010.

Wee White Weeds

near Terradise Nature Preserve, March 20, 2010

A couple of small

annual weeds are exceedingly common and abundant in disturbed open

ground, including agricultural land adjacent to Terradise Nature

preserve in Marion, Ohio. They're flowering now. How is that possible?

Don't flowering plants need time to grow from seed? Yes, they do. And

the way these plants accomplish the feat is by being "winter annuals."

The seeds of these winter annuals germinate in fall or winter, grow

during autumn and also during winter warm spells, remaining dormant but

alive when it's really frigid. Come spring, and "ta-da!!," flowers,

then fruits, releasing seeds that wait until cool weather to sprout,

avoiding summer drought (the adverse season).

Winter-annual weeds in farmland. Marion, Ohio. March 20, 2010.

Harbinger-of-spring (Erigenia

bulbosa)

Winter-annual weeds in farmland. Marion, Ohio. March 20, 2010.

Hoary bitter-cress, Cardamine hirsuta

(Brassicaceae, the mustard family) is known by its abundant basal

pinnatifid leaves that are slightly hairy with long, widely spaced

hairs, and small white flowers.

Hoary bitter-cress. Marion, Ohio. March 20, 2010.

Hoary bitter-cress. Marion, Ohio. March 20, 2010.

Mustard fruits are modifed

capsules --dry many-seeded fruits. Some genera produce long narrow ones

called "siliques," while others produce short squat fruits called

"silicles." Cardamine fruits

are siliques. This is just beginning to develop in the leftmost flower

in the picture below. Other mustard family traits that can be seen here

are the 4 separate sepals, and 4 separate petals, equal in size.

Cardamine flower cluster. March 20, 2010, Marion, Ohio.

Cardamine flower cluster. March 20, 2010, Marion, Ohio.

The other winter-annual weed

here today is common chickweed, Stellaria

media,

a member of the Caryophyllaceae (pink family). This family consists

mainly of opposite-leaved herbs with radially symmetric flowers having

5 petals and sepals, and 5 or 10 stamens. The garden carnation is a

pink, as are sweet William and baby's-breath.

Common chickweed. Marion, Ohio. March 20, 2010.

Common chickweed. Marion, Ohio. March 20, 2010.

Each of chcikweed flower's

five petals are deeply bifid, giving the appearance of a 10-petaled

flower.

Common chickweed flower. Marion, Ohio. March 20, 2010.

Common chickweed flower. Marion, Ohio. March 20, 2010.

Sharon Woods MetroPark, Westerville, Ohio

March 19, 2010

Excepting oddities like skunk

cabbage and various flowering trees that are oblivious to pollinators

(e.g., silver maple, see below), our earliest wildflower is one aptly

dubbed "harbinger of spring," Erigenia

bulbosa (Apiaceae, the carrot family). The species may be

fairly frequent in our deciduous forests, but is easily overlooked

because it protudes only a mini-bit above the leafy ground.

Harbinger of spring at Sharon Woods, Franklin County, Ohio. March 19, 2010.

(A Lichen and Liverwort on American Elm)

Delaware County, Ohio. March 18, 2010

Harbinger of spring at Sharon Woods, Franklin County, Ohio. March 19, 2010.

Erigenia is also known

locally as "pepper and salt" owing to the sharp contrast between the

black stamens and the white petals. Although perhaps not obvious at

first glance, Erigenia is

indeed a fairly typical representative of its family. Note first the

leaves; they're quite lacy, thrice compound in fact, a common

leaf complexity in the family. Moreover, the family is also known as

the

"Umbelliferae" because of its characteristic inflorescence type, the

umbel. An umbel is a flower cluster having stalked flowers that are all

attached at one point on the stem, suggestive of an umbrella. Many

umbelliferous plants, including Erigenia,

bear compound umbels consisting of little umbels ("umbellets")

all of which are attached to one spot. The compound umbels of Erigenia, including the one shown

here, typically have three such umbellets.

If you examine the flowers closely (mouseover to see), several more apiaceous features jump out: an inferior ovary (evident on the old petal-less flower on the left), a bicarpellate ovary (evident by the dual style-branches on that flower), pale-colored radially symmetric flowers with sepals "obsolete" (so small they are essentially absent) ...an overall form not much different from, say, Queen Anne's lace.

Corticolous Cryptogams (Epiphytic

Excitement)If you examine the flowers closely (mouseover to see), several more apiaceous features jump out: an inferior ovary (evident on the old petal-less flower on the left), a bicarpellate ovary (evident by the dual style-branches on that flower), pale-colored radially symmetric flowers with sepals "obsolete" (so small they are essentially absent) ...an overall form not much different from, say, Queen Anne's lace.

(A Lichen and Liverwort on American Elm)

Delaware County, Ohio. March 18, 2010

An American elm tree at a a

research preserve (Kraus Woods) in Delaware County, Ohio is the

substrate for several delightful epiphytes.

Elm bark habitat of liverworts and lichens. Delaware , Ohio. March 18, 2010.

Elm bark habitat of liverworts and lichens. Delaware , Ohio. March 18, 2010.

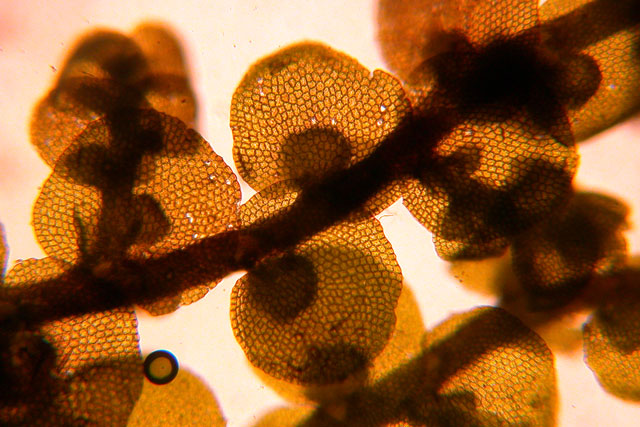

The liverwort is Frullania eboracensis (family

Frullaniaceae), with smallish ovate, distinctively wide-spaced leaves

and a pattern of spawling tree-like doodles on bark, with

stems that are tightly adherent to it.

Frullania eboracensis on elm bark. Delaware County, Ohio. March 18, 2010.

Frullania eboracensis on elm bark. Delaware County, Ohio. March 18, 2010.

Leafy liverworts, which are

more numerous than the relatively featureless thallose types chosen to

depict liverworts in textbooks, can be disturbingly moss-like in

appearance. Leafy liverwort leaves are much more intricate than

those of mosses, the leaves of which are simple, all alike or

nearly so, and arranged in three rows (ranks) around the stem. By

contrast, the leafy liverwort stem typically lays flat, and the upper

and lower leaves are differentiated. There is a pair of upper leaves

which

in many genera have their rear edges folded under (conduplicate,

forming a dorsal lobe ventrsl lobes) and/or are erose or divided

(sometimes

elaborately so). There is nearly always a single row of much

smaller lower leaves.

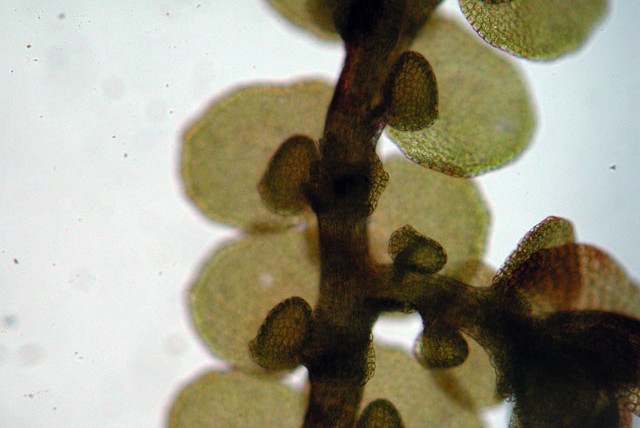

Microscopically, the leaf-lobing of Frullania is most distinctive. The large dorsal lobe, the only leaf part that you see when the plant is growing on the tree, is fairly ordinary --ovate, wide-spaced, and incubously overlapping. Here's a fairly low power microscopic picture of this species taken a few years ago, wheren the large dorsal leaf lobes are blocking a clear view of the reduced ventral leaf lobes.

Frullania eboracensis, dorsal view. Note large dorsal lobes overtopping small ventral lobes.

Microscopically, the leaf-lobing of Frullania is most distinctive. The large dorsal lobe, the only leaf part that you see when the plant is growing on the tree, is fairly ordinary --ovate, wide-spaced, and incubously overlapping. Here's a fairly low power microscopic picture of this species taken a few years ago, wheren the large dorsal leaf lobes are blocking a clear view of the reduced ventral leaf lobes.

Frullania eboracensis, dorsal view. Note large dorsal lobes overtopping small ventral lobes.

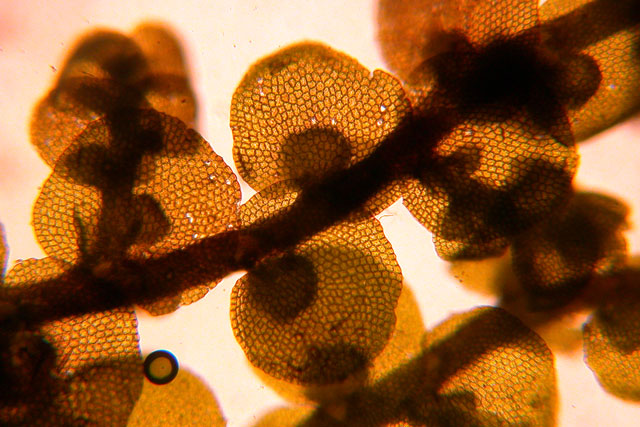

The Frullania ventral lobe is extremely

differentiated. Usually referred to as a "lobule," it is so very

concave

that is resembles a cup. Its function is not known with

certainty, but is suspected to aid in water retention or absorption.

Here's a photo of the underside of Frullania.

Frullania eboracensis ventral view. Note cup-like lobules.

Frullania eboracensis ventral view. Note cup-like lobules.

The underleaves of Frullania eboracensis are small,

wider than long, and bidentate. The photo below is a micrscopic ventral

view focussing on a lower leaf, showing also the cup-like lobule in the

mid-background, and the large dorsal lobe in the distance. Some of the

the cup-like lobules of the Kraus woods Frullania are home to an amazing

little animal --a rotifer (Phylum Rotifera) which I am assuming is one

of the "bdelloid" rotifers (Class Eurotatoria, Subclass Bdellloidea)

famous for consisting only of asexually reproducing females. Rotifers

are surprisingly complex animals, considering they are microscopic. The

are filter-feeders that attach themselves to the substrate and draw in

their food --bacteria, algae, and organic debris --by means of water

currents established by two

helicopter-like sets of whirling cilia.

MOUSEOVER

the IMAGE to see ROTIFER

Frullania underleaf and (mouseover to see) rotifer-inhabited lobule. Delaware, Ohio. March, 2010.

Frullania underleaf and (mouseover to see) rotifer-inhabited lobule. Delaware, Ohio. March, 2010.

Here's a video of the rotifer

in

action.

Rotifer filter-feeds from within

Frullania lobule.

Seeing those little critters

snuggled comfortably in those extraordinary little cups, it's tempting

to think that this might be an elegant mutualism like the one where

aggresive bodyguard ants live in swollen hollow Acacia

thorns in the tropics. Alas, probably not, or at least not in an

obvious way, is this a mutualistic symbiosis. Rotifers in Frullania lobules were the subject

of interesting study by Mary

Puterbaugh and colleagues that was published in The Bryologist

in 2002. Noting that rotifers are frequently found in the lobules, they

propose three plausible hypotheses for the effect of the rotifers on

the liverwort, and four hypotheses for vice versa effects.

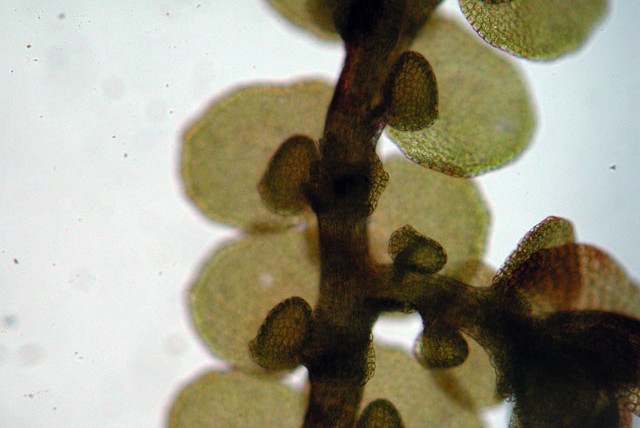

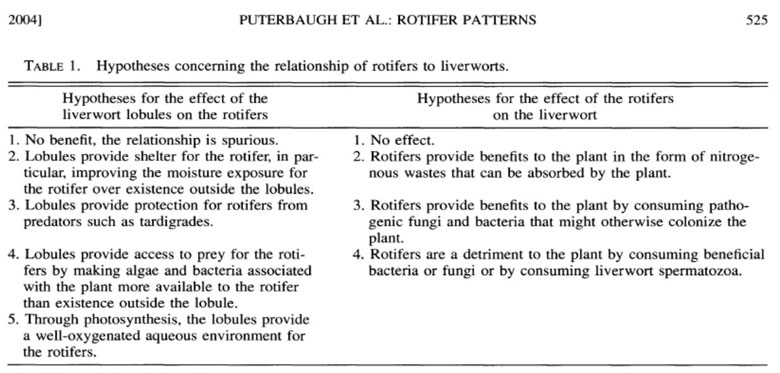

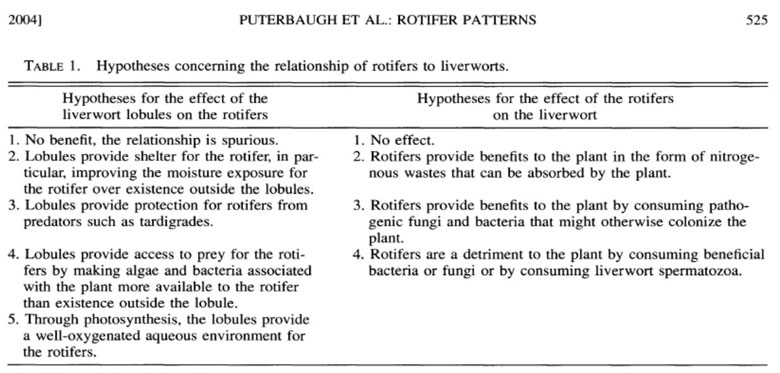

Here's Table 1 from Puterbaugh, M.N., J.J. Skinner and J.M. Miller. 2002. A nonrandom pattern of rotifers inhabitating lobules of the hepatic, Frullania eboracensis. The Bryologist 107:524-530.

In an attempt to lend strength to a working hypothesis that rotifers might benefit the liverwort, and that liverworts helped thusly would be more likely to reproduce, these investigators tallied rotifer presence/absence on thousands of lobes of 84 plants from a site in New York State, recording whether the plants were male-expressing, female-expressing, or nonexpressing, as well as plant size and position on the plant. There was no difference with respect to the plant's reproductive status, but there was a strong tenedency for rotifers to be more frequent in lobules at the edges of plants (nearly 50% of the lobules occupied) compared with central ones (approx. 20% of lobules occupied). Their data "provide tantalizing evidence that the microhabitat throughout a single epiphytic plant is not the same for the rotifer and the explanation for this pattern may provide insight into relationships between bryophytes and invertebrates in general."

Here's Table 1 from Puterbaugh, M.N., J.J. Skinner and J.M. Miller. 2002. A nonrandom pattern of rotifers inhabitating lobules of the hepatic, Frullania eboracensis. The Bryologist 107:524-530.

In an attempt to lend strength to a working hypothesis that rotifers might benefit the liverwort, and that liverworts helped thusly would be more likely to reproduce, these investigators tallied rotifer presence/absence on thousands of lobes of 84 plants from a site in New York State, recording whether the plants were male-expressing, female-expressing, or nonexpressing, as well as plant size and position on the plant. There was no difference with respect to the plant's reproductive status, but there was a strong tenedency for rotifers to be more frequent in lobules at the edges of plants (nearly 50% of the lobules occupied) compared with central ones (approx. 20% of lobules occupied). Their data "provide tantalizing evidence that the microhabitat throughout a single epiphytic plant is not the same for the rotifer and the explanation for this pattern may provide insight into relationships between bryophytes and invertebrates in general."

Frullania has barkmates. Notable

for its abundance and ubiquity on hardwood trees and rocks

throughout the northeastern U.S. and adjacent Canada, even in

shady areas, but inconspicous due to its small size and brown color is

an elegant foliose lichen, orange-cored shadow lichen, Phaeophyscia

rubropulcra. Along with the brownish Phaeophyscia is a bit of a gray

apothecium-bearing foliose lichen I'm guessing is Physcia stellaris.

Foliose lichens on elm bark in Delaware County, Ohio. March 18, 2010.

Foliose lichens on elm bark in Delaware County, Ohio. March 18, 2010.

A diagnostic character

of Phaeophyscia rubropulcra

is the color of the interior layer --the "medulla" is orange-red! This

is evident if you carefully scrape away the upper layer (the cortex).

Ray Showman and Don Flenniken in their excellent manual "The

Macrolichens of Ohio" tell us that this lichen is frequently grazed by

slugs that eat the upper cortex, exposing the orange medulla.

Phaeophyscia rubropulchra, with cortex removed to show orange-red medulla.

Phaeophyscia rubropulchra, with cortex removed to show orange-red medulla.

Silver maple (Acer saccharinum,

family Sapindaceae) is flowering. The flowers are in unisexual clusters.

At the Marion (Ohio) Cemetery, some trees seem to be entirely staminate

(male), and some entirely pistillate (female). Other trees are mixed,

with both male clusters and female ones. Here's a staminate flower

cluster. Note the long slender filaments, an adaptation to cast pollen

into the wind.

Silver maple staminate flower cluster. March 17, 2010.

Silver maple staminate flower cluster. March 17, 2010.

The female flowers present

rabbit-ears-antennae-like stigmas that snag pollen drifting about.

Silver maple pistillate flower cluster. March 17, 2010.

Silver maple pistillate flower cluster. March 17, 2010.

A friend in Delaware, Ohio

invited me to visit her profuse and lively display of early-blooming

garden flowers, including these crocuses. Crocuses are in the Iris

family (Iridaceae). The expensive spice saffron is the dried styles and

stigmas of an autumn-flowering Mediterranean species of Crocus.

Crocus in bloom in

Delaware, Ohio. March 17, 2010.

There is an interesting

variety of winter aconite growing in my friend's garden. According to

the ancient "Doctrine of Signatures," whereby a plant's utility in

treating ailments of a particular body part is revealed by its

resemblance to that body part, these plants can fix eye problems!

Winter aconite, variety "ocularis" in Delaware, Ohio. March 17, 2010.

Winter aconite, variety "ocularis" in Delaware, Ohio. March 17, 2010.

A fabulous filbet shrub is in

bloom. This member of the birch family (Corylaceae) exhibits a fairly

common nut-tree pollination syndrome, that of being monoecious, with

staminate flowers uber-numerous and teeny-tiny, presented in long

drooping catkins. The female flowers are fewer in number. In this

case the female flowers are in minuscule ovoid catkins, one of which is

seen in the picture below cradled by the peducle of the terminal male

catkin.

MOUSEOVER

the IMAGE to see ZOOM-CROP of FEMALE CATKIN

Filbert flowering freely in Delaware, Ohio. March 17, 2010.

Tales from the Cryptogam

Greenlawn Cemetery

Columbus, Ohio. March 14, 2010)

Mildflowers (urban garden plants)

Columbus, Ohio. March 10, 2010

Iconically Poking Through The Snow

Skunk Cabbage in Delaware, Ohio. March 8, 2010

Filbert flowering freely in Delaware, Ohio. March 17, 2010.

Tales from the Cryptogam

Greenlawn Cemetery

Columbus, Ohio. March 14, 2010)

An especially

natural-looking

mausoleum at Greenlawn Cemetery is the substrate for a sweet suite of

mosses and lichens, organisms that, along with

ferns and other primitive vascular plants, are sometimes called

"cryptogams," a term that literally means "hidden marriage" because of

the secrecy, relative to

that of seed plants, of their reproductive methods.

Cryptogam substrate at Greenlawn Cemetery. Columbus, Ohio. March 14, 2010.

Cryptogam substrate at Greenlawn Cemetery. Columbus, Ohio. March 14, 2010.

This is very spooky. There's

something incubous here! Is is a male evil spirit, or a vexing

problem?

No, it's just an incubous liverwort. "Incubous," not quite the same word as "incubus," is a

leaf-arrangement term that describes flat-laying liverworts the leaves

of which overlap (Venetian blind-like) such that the forward edge of

each

leaf lays on top of the back edge of the leaf in front of it. Incubus

leafy liverworts are less numerous than succubous (not succubus, the female evil spirit)

ones.

Here's a picture. The liverwort is Porella platyphylla (family Porellaceae), a very widespread species of leafy liverwort. Leafy liverworts are more common than the flat and relatively featureless thallose ones most often shown in textbooks.

Porella platyphylla, an incubus leafy liverwort. March 14, 2010.

Alongside the liverwort are some mosses. Distintively dark, almost blackish when dry but looking quite green today, patches of Schistidium rivulare (family Grimmiaceae) are abundant, along with a very bright green moss that is "julaceous,"i.e., smoothly cylindric like a worm or a catkin --Entodon seductrix (family Entodontaceae).

Two mosses mingle. March 14, 2010.

Here's a picture. The liverwort is Porella platyphylla (family Porellaceae), a very widespread species of leafy liverwort. Leafy liverworts are more common than the flat and relatively featureless thallose ones most often shown in textbooks.

Porella platyphylla, an incubus leafy liverwort. March 14, 2010.

Alongside the liverwort are some mosses. Distintively dark, almost blackish when dry but looking quite green today, patches of Schistidium rivulare (family Grimmiaceae) are abundant, along with a very bright green moss that is "julaceous,"i.e., smoothly cylindric like a worm or a catkin --Entodon seductrix (family Entodontaceae).

Two mosses mingle. March 14, 2010.

There's a ghostly white

foliose lichen here. Was it scared by the incubus (liverwort) perhaps?

No, it's actually white because it is extremely "pruinose" (having a

powdery bloom) all over the upper surface. This is probably Physconia leucoleiptes.

Ghostly white foliose lichen at Greenlawn Cemetery. Columbus, Ohio. March 14, 2010

Ghostly white foliose lichen at Greenlawn Cemetery. Columbus, Ohio. March 14, 2010

Mildflowers (urban garden plants)

Columbus, Ohio. March 10, 2010

Early-blooming garden plants

might be called

"mildflowers." While not wildflowers, they are nonetheless intriguing

and

welcome evidence that spring has sprung. Winter aconite (Eranthis hyemale,

family Ranunculaceae) is a Eurasian species that reportedly also occurs

sparingly in wild places, but it is not regarded as invasive.

Winter aconite. Columbus, Ohio. March 10, 2010.

Winter aconite. Columbus, Ohio. March 10, 2010.

A common asscociate of the

aconite is snowdrops, Galanthus

nivale.

This is a member of the Amaryllidaceae, a monocot family closely

related to

the Liliaceae, differing from the lilies primarly in its inferior

ovary. While we have no native members of the Amaryllidaceae in Ohio,

we do have two genera that were formerly placed in it: Hypoxis (star-grass, family

Liliceae) and Manfreda

(American aloe, Agavaceae).

Snowdrops. Columbus, Ohio. March 10, 2010.

Snowdrops. Columbus, Ohio. March 10, 2010.

Iconically Poking Through The Snow

Skunk Cabbage in Delaware, Ohio. March 8, 2010

Skunk cabbage, Symploparpus foetidus

(Araceae, the arum family) is one of only a few plants that

exhibit thermogenesis --they get hot! The utility of generating heat

is apparently to increase the volatility of odoriferous compounds that

attract early-emerging pollinators.

Skunk cabbage has melted the snow around it. March 8, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.

It's intriguing to see circular patches of melted snow surrounding the infloresences.

Skunk cabbages have melted the snow around themselves. March 8, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.

Skunk cabbage has melted the snow around it. March 8, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.

It's intriguing to see circular patches of melted snow surrounding the infloresences.

Skunk cabbages have melted the snow around themselves. March 8, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.

While the primary function of

the thermogenesis is to facilitate pollination, it seems reasonable to

assume that the snow-melting effect is beneficial also. Plants buried

beneath snow would be inaccessible to insects.

Skunk cabbage in a little snow cave. March 8, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.

Skunk cabbage in a little snow cave. March 8, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.