|

|

Welcome

to bobklips.com, the website of Bob Klips, a plant enthusiast living in

Columbus, Ohio. ..................................................................................................................... Bio-blitz

at Deep Woods Farm

August 15-16, 2009 In memorium. Dave Blyth. At the time of this writing (October 4, 2009) it is with great sadness that the many friends of Dave Blyth learned of his passing last week, at age 92. The owner and primary land steward of Deep Woods Farm, Dave was fun and smart, always friendly, engaging, and extremely hospitable. His quick wit, good humor and lifelong, principled interest in people, nature, and society has been, and will remain, an inspiration to anyone lucky enough to have spent any time with him. Here's a picture of Dave at the first bio-blitz, in September, 2003. He will be missed.  Deep

Woods Farm, a privately

owned nature preserve in Hocking County, Ohio, is the site of an

ongoing "all-taxa biotic inventory" (ATBI). This is a joint effort of

of

many Ohio naturalists, sponsored by the Ohio Biological Survey, to

assemble a list of all the organisms present here. Both by itself and

in conjunction with similar efforts in Ohio and elsewhere, this will

help gauge the importance of land preservation in

maintaining Ohio's

biodiversity. As part of the Deep Woods ATBI, during most years a

weekend is set

aside for a "bio-blitz," a marathon effort to tally as many species as

possible during a 24-hour period. It was a great pleasure this weekend

to join in the blitz, looking for mosses and also looking

over shoulders to see what interesting things people

have

found.

On the way to the preserve, it was fun to stop and examine some roadside weeds close-up. In a dry open field there is a knapweed I think is brown knapweed, Centaurea jacea (family Asteraceae).  Brown knapweed near Laurelville, Hocking County, Ohio. August 14, 2009. A

striking feature of most

knapweeds is their ragged-edged phyllaries (involucral bracts). These

are small leaf-like spirally arranged appendages that surround the base

of the clump of tiny individual flowers that comprises the aster family

capitulum (head) --a flower cluster (inflorescence) that simulates an

individual

bloom.

Here's a magnified view of the knapweed phyllaries.  Phyllaries (involucral bracts) of brown knapweed. Along

the banks of creeks in

the vicinity, a particularly troublesome Asian weed forms vast stands

to the near exclusuion of other species. This is Japanese knotweed, Polygonum cuspidatum

(family

Polygonaceae).

A large stand of Japanese knotweed near Laurelville, Hocking County, Ohio. August 14, 2009. The

species bears somewhat

attractive sprays of small white flowers. According to Kaufman and

Kaufman (2007) in their excellent book "Invasive Plants" (Stackpole

Books), Japanese knotweed was introduced into North America in the late

1800's as an ornamental, for fodder, and for erosion control. They tell

us the young stems are edible, with a flavor similar to rhubarb.

Japanese knotweed flowers. August 14, 2009. Hocking County, Ohio. Instead of camping out at the preserve as in past years, we slept at the house of friend who lives just a mile away, on a very rural road. Alongside the garage next to the house there is great specimen of a somewhat uncommon tree tree, persimmon (Diospyros virginiana, family Ebenaceae, the ebony family). It a southern tree that is essentially absent from the area of the Wisconsin glaciation, i..e., the northern half of Ohio. E. Lucy Braun in her landmark "The Woody Plants of Ohio" (Ohio State University Press) tells us that the genus Diospyros is very old, abundantly represented and widely distributed in the Cretaceous period, i.e., when dinosaurs were present, and continuing into the first part of the Cenozoic (the age of mammals). Mainly a tropical genus, its range became contracted as climates cooled with the advance of the Pleistocene glacial ice. Ebony wood, known for its extreme hardness, is derived from various Diospyros species. Our persimmon has very distinctive bark, deeply divided into nearly square blocks. MOUSEOVER

the IMAGE to see

the bark.

Persimmon foliage is fairly indistinctive. The fruits, when present, are a giveaway for ID'ing this tree. It's a pinkish-orange berry 2-4 cm in diameter, famous for being very astringent when unripe (although it might appear to be ripe), and sweet and edible when ripe (at which time it is soft and mushy, appearing over-ripe). The persimmon you are apt to see at the grocery is a Chinese species, D. cafi, cultivated in the southern states and California. The persimmon shown here is not ripe yet. MOUSEOVER

the IMAGE to see

the fruit.

Persimmon.

August 15, 2009. Hocking County, Ohio.

Another tree treat

growing alongside the house is

sassafrass, Sassafras

albidum

in the family Lauraceae, the laurel family. E. Lucy Braun, in a

passage similar to the one about persimmon, relates "our

sassafras of eastern north America and two Asiatic species are the last

survivors of a long line of Sassafras

dating back, in the fossil record,

to the close of Lower Cretaceous time, or almost to the beginning of

the record of dicotyledenous trees. Leaves, almost throughout these

millions of years, have been similar to those of existing species:

3-lobed or mitten-like, or sometimes entire." The fruit is a blue drupe about 1 cm long, supported by a club-shaped red pedicel. All parts of the tree are very pungently aromatic. Oil of sassafras, derived from the roots, has been used to perfume soaps and as a base for some perfumes. E. Lucy Braun states "An over-dose of the oil may act as a narcotic." American root beer was originally formulated using sassafras root extract, and pleasant-tasting sassafras root tea was quite popular until the 1960's when it was determined that the principal ingredient, safrole, might be carcinogenic. Since then, the sale of safrole-containg products was banned by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, and nowadays if you see any sassafras extract for sale, it is safrole-free, which seems pretty lame to me, like decaffeinated coffee. What's the point?  Sassafras tree in fruit. Hocking County, Ohio. August 15, 2009. Eventually

we made it to the

bio-blitz. It turned out to be a great day for mushrooms. Especially

abundant, although a little too far along to make an appealing meal,

the prized golden chanterelle, Cantharellus

cibarius, is rendered

distinctive by

its widely spaced gills that are narrow but

blunt, extending down the stalk.

Golden chanterelle at Deep Woods Farm, August 15, 2009. A

strikingly colored mushroom

is

common today.

According to Orton Miller in his "Mushrooms of North

America" (1977; E.P. Dutton), its genus, Cortinarius,

has the most species

in North America. Cortinarius

is distinguished by having a

spider-web-like (cortinous) veil bewteen the cap and stem. The

distinctive veil is not present on older specimens like this one,

however,

so other

features were used to ID the specimen. I believe it is Cortinarius violaceous.

Cortinarous mushroom at Deep Woods Farm. August 15, 2009. The

undersurface displays

gills, upon which are located the spore-producing cells (microscopic basidia).

Undersurface of Cortinarius mushroom. August 15, 2009. Deep Woods. Hocking County, Ohio. A

familar and easily

identified mushroom is the "fly agaric," Amanita muscaria.

The amanitas are

generally recognized by having both a "universal veil" that surrounds

the entire fruiting body, i.e., both the cap and the stem while it is

young, and also a "partial veil" extending from the edge of the

cap to the stem. Remnants of the universal veil are seen on

the

top of the cap

and sometimes also at the upper edge of the swollen stem-base, while a

partial veil remnant forms a skirt-like ring around the stem just

below the cap.

Amanita muscaria at Deep Woods, Hocking County, Ohio. August 15, 2009. Quite

a number of mushrooms and other fungi were brought back to the lab for

identification. Here's a table full of them. The one near the lower

left is especially striking (mouseover to see a closeup).

MOUSEOVER

the IMAGE to see "old man of the woods."

Various

fungi

brought back for examination at the Deep Woods bio-blitz.

August 15, 2009.

The

prominence of fungi at this year's bio-blitz was not limited just to

specimens in the woods.

Al makes a fungal fashion statement at the Deep Woods bio-blitz while Gary diligently adds species to the blitz-list. Most

of the organisms tallied

in the Deep Woods ATBI are insects. That figures, of course, since they

are indeed the most numerous animals. But key here are people

knowledgable enough to recognize all the different kinds.

Gary and Holly examine closely their catch from an insect sweep. August 16, 2009. Alongside

the entomologists

in the open meadow are some unusual wildflowers. One of these is wild

sensitive plant, Chamaecrista

nictitans (Family

Caesalpinaceae, the "I am really confused

...am

I a legume or what?" family). It's congeric with "partridge-pea," (C. fasciculata),

a prairie

wildflower that has similar foliage, but larger flowers.

Wild sensitive plant at Deep Woods Farm. Aygust 16, 2009. ...and

a little orchid

--slender ladies' tresses, Spiranthes

gracilis. E. Lucy Braun tells

us that this is "one of the most

frequent species of Spiranthes,

occurring in open woods, fields, pastures, prairies, in moist or dry,

acid or alkaline soils, almost throughout the eastern half of the

country."

Orchids are trying very hard to be extremely cool like milkweeds, so they have highly modified flowers with several parts fused, and their pollen is carried en masse in pollinia. Nice try, orchids.  Slender ladies's tresses orchid at Deep Woods Farm August 16, 2009. Protandry, 2 Lespedeza species, a small orchid, and more. Hocking County, Ohio, August 5, 2009. This week I had the pleasure of tagging along on an Ohio State University "Local Flora" class field trip to Deep Woods Preserve, a privately owned 282-acre tract in Hocking County, Ohio. One of the first plants we encountered is rose-pink, Sabatia angularis (Family Gentianaceae).  Rose-pink at Deep Woods, Hocking County, Ohio. August 5, 2009. Rose-pink

is a member of the gentian

family (Gentianaceae). Plants in this family are mostly opposite-leaved

herbs with 4-5 parted flowers that are perfect (hermaphroditic), have a

superior ovary, are radially symmetric, and have their petals fused to

one another. The

stamens, which are as many as the corolla-lobes, are

inserted on

the corolla-tube between the corolla-lobes (which is the usual

location for stamens). In Ohio there are 15 species in the

Gentianaceae, all but one of which are native. In addition to our

single

species of Sabatia,

the family include the screw-stems (Bartonia,

2 species), American columbo (Frasera,

1 species), gentians (Gentiana,

6 species), stiff-gentian (Gentianella,

1 species), fringed

gentians (Gentianopsis,

2 species), and pennywort (Oblaria,

1 species). The sole introduced member is branching centaury, Centaurium

pulchellum.

Below, two other gentian family members, from different seasons and localities.   Representative members of the gentian family in Ohio. Left: bottle-gentian (Gentiana andrewsii), at a restored prairie in Marion County, Sept 5, 2005. Right: pennywort (Oblaria virginica), at a Hocking County woodland, April 24, 2004. The rose-pink flowers at Deep Woods display an interesting adaptation to minimize self-pollination. This is a type of "dichogamy" --a condition wherein the differently sexed organs of a hermaphotditic plant mature at different times, an adaptation to minimize self-pollination. This particular example, where the female stigma doesn't become receptive until after the anthers have shed their pollen, is termed "protandry," a word that translates as "male first." (The opposite condition is called "protogyny.") Here are some close-up photos revealing the sequential maturation of rose-pink flower parts. Note that protandry is not a perfect means to avoid selfing, because while the different sets of floral organs within a flower mature sequentially, different flowers on the same plant are likely to be of different ages, and so there are many instances of simultaneously mature male and female parts on a given plant. Hence a bee could easly go from one flower to another on that plant. An early-stage (male stage) flower:  Early (male) stage of rose-pink flowering. August 5, 2009 at Deep Wood Preserve. A

mid-stage (female stage) flower:

Middle (female) stage of rose-pink flowering. August 5, 2009 at Deep Wood Preserve. After pollination has occured, the lower part of the pistil --the ovary --begins swelling, developing into a fruit. (A fruit is a ripened ovary containing seeds.)  Late (post-pollination) stage of rose-pink flowering, August 5, 2009 at Deep Woods Preserve. We hiked up to a dry meadow having thin acid soil that is the home of several wildflowers I've never seen before.  Dry meadow home of several unusual plants. August 5, 2009. Deep Woods, Hocking County, Ohio. A

perennial debate among nature lovers

concerns the value of common names. While common names certainly have

shortcomings such as the fact that the same common name may apply to

different plants (How many 'snakeroots' are there?!), and their lack of

information content

(Marsh 'marigold' isn't a marigold, and prickly 'ash' isn't an ash!),

recently there have been so many

changes in scientific names that the relative consisteny of common

names is a strong point in their favor.

I recently heard this maxim: "While scientific names change from time to time, common names change from place to place." One of the species in this meadow is a shrub so low-growing it could be mistaken for an herb, and is a case in favor of common names. This is St. Andrew's cross, Ascyrium hypericoides ...no, I mean Hypericum hypericoides, in the family Hypericaceae.  St. Andrew's cross at Deep Woods Preserve. August 5, 2009. Unlike

other members of the genus Hypericum

(which

are generally known as "St. John's-worts"), this one has its flower

parts in 4's (4 petals, 4 sepals), while the other, more typical,

traditional hyperica are 5-merous.

The old wildflower book ID'd it quickly and easily as St. Andrew's cross, Ascyrum hypericoides, and after a cursory examination of a list of Ohio plants failed to locate that genus, there was a momentary surge of naive excitement this might be a new species for the State. Very momentary excitement of course, as the common name on the State list jumped out, next to its new scientific name, as it is now placed in the genus Hypericum.  St. Andrews's cross (Hypericum hypericoides). Aug 5, 2009. I'm

assuming that this plant is "Saint"

Andrew's cross. But "St." is also the abbreviation for "street." If

there was somebody named "Street" who performed miracles and thus

became canonized, and then a municipality named a thoroughfare after

him, would there be a sign identifying the road as "St. St. St."?

Nearby,

two species of bush-clover (genus Lespedeza,

family Fabaceae) are flowering. These have trifoliolate leaves with

untoothed leaflets, blue or purple to pinkish or white flowers produced

in the axils of the upper leaves, and one-seeded fruits. The genus is

quite similar to tick-trefoil (Desmodium),

except that genus

produces several seeded fruits.

The more conspicuous bush-clover of this meadow is hairy bush-clover, Lespedeza hirta. It's about 2 feet tall, yellowish-white flowered, with obovate leaflets. The species is said to be abundant in dry soil.  Hairy bush-clover. August 5, 2009. Close-up, hairy

bush-clover displays

well the Fabaceae flower structure: strongly bilateral symmetry with a

single especially large upper petal termed the "standard" (or

"banner"), two smaller lateral petals (the "wings"), and two lower

petals fused at their tips to comrise the "keel," which closely

envelopes the sexual parts of the flower (stamens and pistil).

Hairy bush-clover flowers. August 5, 2009. Deep Woods, Hocking County, Ohio. The other Lesdedeza here is a low-growing viney one, trailing bush-clover, L. procumbens.  Trailing bush-clover at Deep Woods Preserve. August 5, 2009. In the upland hardwood forest alongside the dry meadow, an orchid is in bloom. It's green woodland orchid, Platanthera clavellata. (You may have learned it as Habenaria.) This small-flowered orchid is green-leaved (i.e., not wholly saprophytic), and bears its leaves along the stem. The flowers each have a long spur at the base of the largest petal (a petal that is termed the "lip").  The green woodland orchid, Platanthera clavellata. August 5, 2009. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio Orchid

flowers are highly modified. Most

of the distinctive traits aren't evident in the picture below.

Reminiscent of the milkweeds, the orchid style, stigmas, and

stamens are

united to form a central "column," and, also like the milkweeds, the

pollen is dispersed not as individual grains, but alltogether in

coherent masses --"pollinia" --each pollinium derived from one

pollen-producing chamber of an anther.

In most orchid genera the flowers are "resupinate," i.e., presented

upside-down, such that the large "lip" petal which is anatomically the

upper one, is situated downward. Unlike milkweeds, which are pollinated

by an array of generalist bee and butterfly flower visitors, orchids

tend to have particular pollinators. I don't know of the little bee or

wasp thing sitting on the flower is its pollinator or just a passer-by.

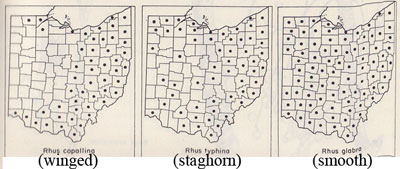

Platanthera clavellata flowers at Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio. Oh, duh!! The flowers have a big long spur. With nectar at the base, such a spur is an adaptation for a long-probiscis lepidopteran of some sort, right? The wee wasp must be a sight-seer. At the woodland edges, a sumac shrub is in flower --this is winged, or shining, sumac, Rhus copallina (family Anacardiaceae, the cashew family --also the poison-ivy/poison sumac family ...and pistachio and mango as well).  Winged (shining) sumac shrub at Deep Woods Preserve. August 5, 2009. As

do many plants, this sumac has a

distirbution in Ohio that is strongly corellated with soil chemistry.

In this case, it's something of an acidophile (meaning "acid lover,"

not to be

confusd with Timothy Leary). E. Lucy Braun, in her magnificant "The

Woody Plants of Ohio" (1961, 1989; The Ohio State University Press)

explains that winged sumac in Ohio is "largely confined to the

Allegheny Plateau, and acid soils of the flats of southwestern Ohio

(Illinoian Till Plain) and Lake area of northern Ohio."

Here are range maps of what she refers to as the "red-berried sumacs" (she doesn't include fragrant sumac in that category).  Sumac (Rhus) ranges in Ohio. "Woody Plants of Ohio" (OSU Press). Winged,

or shining, sumac is appropriately

named. Its leaves are shiny with a winged rachis.

Winged, or shining, sumac leaf. August 5, 2009. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio. The

flowers of the Anacardiaceae are

small, radially symmetric, perfect (i.e., hermaphrotic) or in some

instances unisexual, and

5-merous with a 5-lobed calyx, 5 separate greenish-white petals, and 5

stamens alternating with the petals. Moreover --and this is the

interesting part

--the stamens are inserted beneath a nectariferous disk surrounding the

ovary!

Here's an individual flower on this shrub, showing the nectariferous disk. Note also the 3 styles atop the pistil, an indicator that the pistil is composed of three seed-bearing units (carpels).  Winged sumac flower showing nectariferous disk surounding the ovary. Note also the 5 stamens alternating with the petals, and the 3 styles atop the ovary. A

low-lying seepy area is home to several

ferns characteristic of wet places. Here, the class is studying

sentitive fern (Onolea

sensibilis) in a location where

cinnamon

fern and royal fern are also abundant.

OSU Local Flora class studying frrns at Deep Woods Preserve. August 5, 2009. Other ferns at the preserve are displaying reproductive features. One of them is the silvery glade fern, Athryrium thelypteroides (family Dryopteridaceae). (Young whipper-snappers are calling this fern "Deparia acrostichoides," which is a particularly pernicous name-change because the specific epithet "acrostichoides" also belongs to a wholly different fern --Christmas fern, Polystichum acrostichoides --thus inviting confusion! Nomenclature on this web site and in my real-life Brain on Botany generally follows that used on the "Floristic Quality Assessment Index (FQAI) for Vascular Plants and Mosses for the State of Ohio," by Barbara Andreas, John Mack and James McCormac, 2004, Ohio Environmental Protection Agency.) Silvery

glade fern is a robust fern fern

that grows in circular clusters from a vertical underground stem. Its

leaves are twice-compound. The overal aspect is quite similar to some

of

the woodferns (Dryopteris).

Silvery glade fern at Deep Woods Preserve. August 5, 2009. A

distinguishing characteristic of many

ferns is the manner in which the spore cases (sporangia) are aggregated

beneath the leaf. While the individual sporangia are so minute they

cannot be distinguished without a hand-lens, the sporangia are often

clustered together into clearly visible groups called "sori."

(That's the plural tern; an individual cluster is a "sorus.") During the mid-1970's I had the honor of being shown a very rare fern --Hart's-tongue fern --by a very accomplished botanist, the venerable Mildred Faust of Syracuse, NY. After hiking for quite some time in the wilder portions of Clark Reservation State Park, we finally came upon the sought-after talus slope graced by this magnificant plant, and Mildred Faust pointed to it and said, with a twinkle in her eye "Isn't that a sight for sore eyes?" Sore eyes ...soris, get it?. Hey, at least this story is true! Unlike the somewhat similar wood-ferns, the sori of which are a roundish kidney-shape ("reniform"), glade-fern sori are elongate ("linear").  Silvery glade fern from beneath, showing linear sori. August 5, 2009. Deep Woods. Another aspect of the disposition of the fern sporangia deals with the fact that, when they are developing, they are covered by a protective layer of epidermis called the "indusium." This flash photo shows the indusia --i.e., the protective layer over the developing sporangia.  Silvery galde fern indusia. August 5, 2009. Deep Woods Preserve. In

most ferns the indusium is indeed

composed of an outer layer of leaf cells, and this condition is thus

characterized as being a "true indusium." A few ferns, however, have

the developing sporangia covered not by an outer layer of leaf cells,

but instead by just the curled-under edge of the leaf. Indusium-like in

function but not anatomy, this is termed a "false indusium."

We saw a good example of a false indusium on maidenhair fern (Adiantum pedatum, family Pteridaceae). This fern has an interesting overall leaf morphology; it is compound, but divided into two main segments, each of which is further subdivided into leaflets This composition, termed "pedately divided," is the basis of its specific epithet.  Maidenhair fern at Deep Woods Preserve, August 5, 2009. Hocking County, Ohio. The false indusiua are evident when the fronds are viewed from beneath.  Maidenhair fern showing false indusia. August 5, 2009. Deep Woods Preserve. August 5, 2009. I

took a close-up flash picture of the

false indusium of maidenhair fern. Note the leaf margin, curled under.

False indusium of maidenhair fern. August 5, 2009, Deep Woods Preserve, A couple of opposite-leaved herbs of open wet areas bearing numerous bilaterally summetric flowers with fused petals grace a moist meadow in the floodplain of a creek. One of them is American germander, Teucrium canadense (family Lamiaceae, the mint family). Quite similar in overall form to the hedge-nettles (genus Stachys) and most other mints, which have "bilabiate" (two-lipped) flowers, Teucrium stands apart by having the upper lip of the flower missing!  Americam germander flowers lack an upper lip. August 5, 2009. Deep Woods Preserve.  Square-stemmed monkey flower at Deep Woods Preserve. August 5, 2009. In a moist crevice on a log, a lovely little moss that is not very common, and is easily overlooked, and one of the few mosses with a common name, the "knothole moss," Anacamptodon splachnoides (family Fabroniaceae) is merrily producing sporophytes. The sporania (capsules) have a distinctive shape --compressed below the mouth --that becomes further accentuated as the capsule ages.  The "knothole moss," Anacamptodon splachnoides, at Deep Woods on August 5, 2009. Pickaway County, Ohio. August 4, 2009. Prickly lettuce is flowering along roadsides. It is an alien weed that here is seen alongside another alien weed, (arghhh) poison hemlock, which is in fruit.  Prickly lettuce and poison hemlock. Pickaway County, Ohio. August 4, 2009. The

genus Lactuca is

a member of

the aster

family (Asteraceae), a family in which numerous small flowers are

packed together in a head-like flower cluster (i.e., the inflorescence

is a "capitulum") that simulates an individual large blossom. Moreover,

lettuce is in a subgroup of the aster family that produces just one

type of flower --strap shaped "ligulate" ones. (Radially

symmetric disk flowers are absent.)

This subgroup, traditionally

designated as subfamily Lactucoideae, also

includes

dandelion, chichory, hawkweed, and coltsfoot. Here's a closer view of a

flowering portion of the lettuce plant.

Prickly lettuce. August 4, 2009. Pickaway County, Ohio. Prickly

lettuce bears deeply lobed leaves:

Prickly lettuce leaf. August 4, 2009. Pickaway Cty. OH. ...that

are prickly along the midvein:

Prickly midevein of prickly lettuce. August 4, 2009. Pickaway County, Ohio. The genus Lactuca includes the cultivated lettuce, L. serriola. Like other members of the its subfamily, these plants produces a milky latex sap when injured. The sap of Lactuca is said to have some opium-like pain-relieving and possibly intoxicating qualities. Wild senna (Cassia hebecarpa, family Caesalpinaceae) Columbus, Ohio garden. August 3, 2009. The Caesalpinia family (Caesalpiniaceae) is very close to the legume family (Fabaceae), and has been even considered a subfamily of it. The Caesalpiniaceae is distinguished from the Fabaceae by having the corolla more nearly regular (radially symmetric) than the very strongly bilaterally symmetric legumes (fruits), by having its upper petal inside (not outside) the 2 lateral ones, and by having the 10 stamens free from one another (not partly fused in two groups). The family is primarily an old-world tropical one. In Ohio we have five native genera, of which two --Cassia (wild senna), and Chamaecrista (partridge-pea) are herbs, and three --Cercis (redbud), Gleditsia (honey-locust), and Gymnocladus (Kentucky coffee-tree) --are trees. Cassia hebecarpa is an herbaceous perennial with alternately arranged, pinnately compound leaves. Naturally occuring in moist open woods, roadsides, stream banks and praires, it does quite well in a prairie garden. The specimen shown below is growing in a backyard in the Clintonville neighborhood of Columbus, Ohio.  Wild senna (Cassia hebecarpa). August 3, 2009. Columbus, Ohio. The plants are avidly visited by bumblebees. Bumblebees

visit wild

senna in Columbus, Ohio. August 3, 2009.

Wild senna flowers are

nearly regular (radially

symmetric). Barely evident in the photo below, the upper 3

stamens are sterile, lacking normal anthers. The 7 fertile anthers are

basifix (attached at their base) and open by terminal pores. The

slender

yellow style, with a head-shaped stigma, is visible just above the

lowermost stamen.  Wild senna. August 3, 2009. Columbus, Ohio. Note the upper 3 anther are sterile. See also how the slender style nearly touches the bee's abdomen. Here's

a closeup video

of a bumblebee visiting the wild senna flower. Considering the floral

morphology explicated above, it is very evident that pollen

removal and deposition are likely taking place.

Bumblebee

pollinates wild senna in

Columbus, Ohio. August 3, 2009.

|