|

Welcome

to bobklips.com, the website of Bob Klips, a plant enthusiast living in

Columbus, Ohio.

.....................................................................................................................

Tube

ferns

(Scouring-rush, Equisetum hyemale)

July 28 and August 2, 2009 -Waldo, Marion County, Ohio

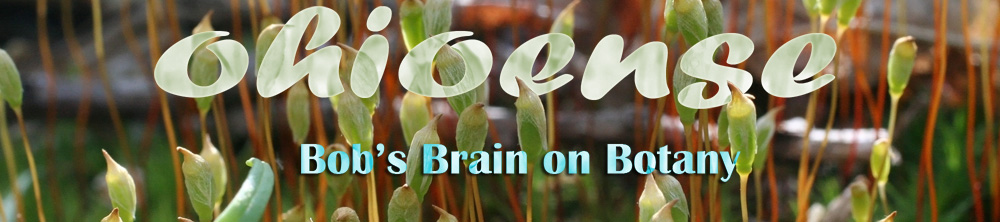

The plant kingdom is divided into a number of divisions, a

category that is equivalent to phylum in the animal

kingdom. Taxonomy is a dynamic science, especially as molecular data

are being used to reveal relationships that might not be apparent based

on morphology alone. Primitive (seedless) vascular plants that occur in

Ohio are a case in point. Several years ago, scouring-rushes and

horsetails, both of which are in the genus Equisetum,

were placed in their own division, the Equisetophyta (also

called

"Sphenophyta"), separate from the ferns (Division Pteridophyta). Both

divisions were likewise separate from the clubmoss/spikemoss/quillwort

group, Division Lycopodophyta.

A more modern view, however, places the ferns and horsetails together

(along with the whisk ferns, a group that doesn't occur in

Ohio), separate from the Lycophytes. Here's a diagram from a

modern college textbook, the lawyers for which will interpret my

including it here as promotion of the text, not copyright infringement,

right?

Please? Pretty please?

Plant kingdom phylogeny from very excellent biology textbook.

(Biology: Concepts and Connections, 6th ed.

Campbell

/ Reece / Taylor / Simon / Dickey)

Here's a picture of the spore-bearing terminal portion of

a scouring-rush. It was taken in a low-lying woodland in

Waldo,

Ohio. What is the location of Waldo? It's near

Marion. Where's Marion?

Tube-fern (scouring-rush) strobilus.

Waldo, Marion County, Ohio. July 28, 2009.

The spore-bearing portion of the plant is a terminal cone called a "strobilus."

The spores themselves are produced in sac-like containers called "sporangia."

To understand the overall arrangement, imagine a six-sided umbrella,

from near the edge of which are attached dangling grocery bages filled

with

popcorn. The popcorn is the spores, the bags are sporangia, and the

umbrella is a peltate (centrally attached) sporangiophore.

Now

imagine rougly one hundred of these umbrellas

attached to a thick post, arranged in a tight spiral. That, in a

nutshell, is the cone-like strobilus. Wait...what part is the nutshell?

No..."nutshell" is just a figure of speech; there is no nutshell.

A close-up taken at night shows this better. This is a portion of the

strobilus. The dark hexagons are the tops of the sporangiophores, from

near the edges of which white bag-like sporangia are attached.

Portion of Equisetum strobilus. Waldo, Marion

County, Ohio. August 2, 2009.

Some intriguing

creatures, suggestive of the giant arthopods that inhabited

Carboniferous swamp forests, were present at the Equisetum

stand tonight.

Creatures on Equisetum hyemale at night. August 2,

2009. Waldo, Marion County, Ohio.

Left: sowbug. Right: tree-cricket.

The sowbug is noteworthy because it is a terrestrial, not aquatic,

crustacean. Sowbugs (with tail-like structures at rear end, cannot roll

up into ball) and pillbugs (lacking tail-like structures at rear end,

can roll up into ball) are our only terrestrial crustaceans. A crayfish

(crawdad) is a typical aquatic crustacean.

Wild

"petunia" and the scroph-like family Acanthaceae.

Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve

Pickaway County, Ohio. July 24, 2009.

A striking wildflower

that shows up now, when there are few others so conspicuous,

wild petunia, Ruellia strepens, occurs in moist

woods from New Jersey to Indiana, south to S. Carolina, Alabama, and

Texas. Here it occurs alongside a boardwalk in a low-lying wooded

portion of Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve in Pickaway County, Ohio.

Wild petunia at Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve. Pickaway County,

Ohio. July 23, 2009.

The common name

"petunia" is just so-so with respect to information content. The true

petunia (genus Petunia) is in a different, but

closely related family, the Solanaceae (nightshade fam.), and while

there is a southeastern native Petunia, it doesn't

occur this far north.

Ruellia is in the Acanthaceae (Acanthus

family), a family with only 4

northeastern U.S. genera, only two of which occur in Ohio. The family

is much more numerous in tropical regions. It is very similar, and

closely related to, a family that is prominent here, the

Scrophulariaceae (figwort family). Are you curious about the

differences between the mainly tropical Acanthaceae and our temperate

Scrophs? Me too! A very useful reference for sorting these things out

is "Vascular Plant Families" 1977. Payne, J.P., Mad River Press).

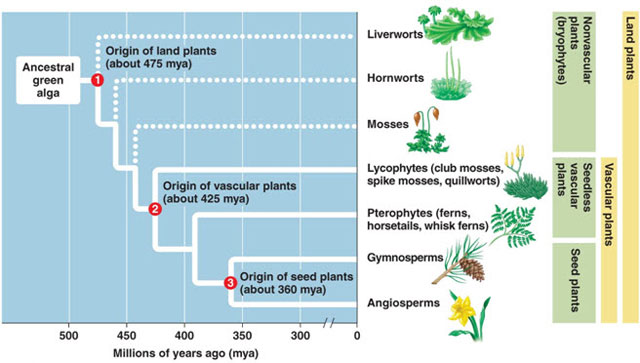

Table comparing several similar plant families.

This table makes things

very clear. Members of the Acanthaceae typically have 2 stamens, two of

which are different somehow from the other two (hence the "2+2"

designation), but they may in rare instances have two

stamens, or five stamens. By contrast, the scrophs typically

have 2 stamens, two of which are different somehow from

the other two (the "2+2" designation), but they may rarely

have two stamens, or five stamens. A further distinction is offered by

the number of chambers (locules) of the ovary. Members of the

Acanthaceae have 2 locules. whereas scrophs have 2 locules. A final

difference is in the placentation type, i.e., to what portion of the

interior of the ovary the seeds are attached. Acanths (is that a word?)

have their seeds attached along the inner portion where the locules are

fused; this is called "axillary" placentation, and it clearly separates

them from Scrophulariaceae, the members of which have axillary

placentation (i.e., attached along the inner portion where the locules

are fused). I'm glad we got that figured out!

We didn't? Oh right...they're the same insofar as stamens, locules and

placentation are concerned (and a host of other characters). Is "showy

bracts" really important? It doesn't seem like the type of fundamental

thing that would be used for distinguishing a plant family, but at

least it is evident in the picture below, taken in late June at a

restored prairie approx. 80 mile north of Stage's Pond.

Wild petunia. Note leaf-like showy (?) bracts. Marion County, Ohio.

June 23, 2009.

Evidentally there are further, even more techinical features that do

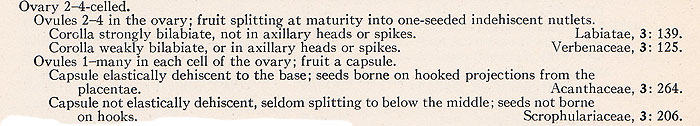

separate the scrops from the acanths. Here is a portion of the plant

families key in the best book ever written --The

New Britton and Brown Illustrated Flora of the Northeastern

United States and Adjacent Canada, H.A. Gleason (1952). Evidentally the

capsules of Ruellia are elastically dehiscent and

their

seeds are borne on hooked projections. This requires further study.

Details separating Scrophulariaceae and Acanthaceae in "The New Britton

and Brown" (1952).

[Note: "Vascular Plant

Families" really is a

terrific book.

These things are hard to simplify, and pointing out this scrop/acanth

confusion is just light-hearted kidding. J P. Smith, Jr. does a great

job explaining plant taxonomy, and the illustrations by Kathryn Simpson

are excellent! Buy this book!]

Meanwhile, a so-called "pollen bee," i.e., a non-colonial one that

provisions her nest with pollen that she gathers from flowers but which

does not store copious amounts of nectar (honey), assiduously removes

pollen grains from a wild petunia flower at Stage's Pond.

Pollen bee foraging

on wild petunia (Ruellia strepens).

Stage's Pond State Nature Preserve, Pickaway County, Ohio. July 24,

2009.

Incidentally, our other

Ohio genus in the Acanthaceae is Justicia, water-willow.

It is an emergent aquatic plant, occurring in mud and shallow water.

Our species, J. americana

is extremely abundant along the Scioto and Olentangy Rivers in

Columbus. Here is water-willow along the Scioto, just s. of the

Fissinger Rd. Bridge (photo taken 2007).

Water-willow along the Scioto River, Columbus, Ohio. June 23, 2007.

...here is an

individual water-willow plant. Note the opposite leaves and head-like

flower spikes.

Water-willow. June 23, 2007. Columbus, Ohio.

...and a closeup of the

flower cluster. Note strongly bilaterally symmetric flowers

each with only 2 stamens.

Water-willow flowers. June 23, 2007. Columbus, Ohio.

...and apparently the

honeybees like them.

Honeybee visiting water-willow. June 23, 2007. Columbus, Ohio.

Two too

terrible teasels.

(Dipsacus laciniatus and D. fullonum)

July 21-23, 2009. Delaware, Ohio.

There is a weed spreading south along Rte. 23 so

fast I'm surprised the police haven't pulled it over for

speeding. Perhaps they're busy issuing a ticket to the emerald ash

borer. The weed is cut-leaved teasel, Dipsacus laciniatus

(family Dipsacaceae). This species has changed its status

markedly since mid- (last)-century when, in the best book ever written

--The New Britton and Brown Illustrated Flora of the Northeastern

United States and Adjacent Canada, H.A. Gleason (1952) described it as

"rarely adventive, native of Europe.

Cut-leaved teasel along Rte. 23 in Delaware Ohio. July 21, 2009.

There's another, much

more well known teasel that is also an aggressive weed, Fuller's teasel

(D. fullonum).

This week, the annual Anti-apartheid Leaders Invasive Plants

Conference was held in Columbus. I was asked to lead a couple

of tours, and to be sure to point out both Dipsacus

species. In the morning I showed the plants to a group of visitors that

included Nelson Mandela but not Desmond the former Archbishop. Desmond

came on the afternoon tour, however. When I was asked by the conference

organizer whether Desmond had a chance to see them as did

Nelson, I replied "I took Tutu too to two too terrible teasels."

That story isn't true. But there are truly two too terrible teasels.

The "new" one, cut-leaved teasel, is extremely abundant

across much of the grassland at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area in

Wyandot and Marion Counties. The managers there are valiantly

battling it with mowers and herbicides.

Dipsacus fullonum, the "old" teasel, is a problem in some

prairie restorations as well as being a common roadside weed.

Nomenclatural

note: it was until recently referred to as common teasel, with

the scientfic name Dipsacus sylvestris, at which

time the name "fuller's teasel" (scientific name: D. fullonum)

was reserved for a variety with especially stiff, hooked awns.

This feature makes the

heads useful for fulling,

i.e., fluffing up, the surface of cloth.

Here are both teasels, mingled along Delaware, Ohio roadsides.

Two too terrible teasels in Delaware, Ohio. July 21, 2009.

Left: fuller's (common) teasel D. fullonum. Right:

cut-leaved teasel D. laciniatus.

Two differences between

the species are on display in the photo above. On the left, D.

fullonum

has flowering branches (peduncles) that diverge widely (like the letter

"Y"), and the flowers are pink. On the right, D. laciniatus

has much more erect peducles (like someone pointed a gun at it and said

"stick 'em up!"), at the ends of which are heads of white

flowers.

Here are some single-species shot of the two species. First, D.

fullonum.

Fuller's (common) teasel. Delaware, Ohio. July 23, 2009.

Now, D.

laciniatus.

Cut-leaved teasel. Delaware, Ohio. July 23, 2009.

The other striking diff

between the spp. is the leaves. Cut-leaved is cut-leaved. The other

isn't.

Two too terrible teasels in Delaware,

Ohio. July 21, 2009.

Left: fuller's (common) teasel D. fullonum. Right:

cut-leaved teasel D. laciniatus.

Here's a video that shows a good side

of fuller's teasel: bumblebees like it. The bee seems

oblivious to the traffic

rushing by.

Bumblebee foraging on fuller's

teasel. July 21, 2009.

Hydrastis

Harvestman

("Daddy-long-legs" on goldenseal)

Delaware County, Ohio July 17, 2009

In a rich undisturbed

woodland in northern Delaware County there is a nice colony of

goldenseal (Hydrastis canadensis,

family Ranunculaceae). Its knotty yellow rhizomes are reputed to have

medicinal properties, thus, like black cohosh and ginseng,

over-collection for the herb trade has nearly exterminated the plant in

some areas. Goldenseal is a perennial herb with basal and alternate

leaves and a solitary terminal flower. Like many other members of the

buttercup family, its flowers have an "apocarpous gynoecium," i.e.,

each flower has several-many stigma-style-ovary units (carpels) that

are separate from one another. Thus a single flower (or better yet a

married one) (or at least one in a committed long-term relationship)

can develop into several-many fruits. If they are clustered together,

as they are in goldenseal, the cluster, simulating an individual fruit,

is termed an "aggegrate fruit." Goldenseal produces an aggregate of

small berries that is reminiscent of a raspberry or a blackberry.

(Raspberries and blackberries are not berries or even aggregates of

them; they are aggregates of tiny cherry-like fruits called

"drupelets.") Here's goldenseal.

Goldenseal plants in fruit in Delaware County, Ohio. July 17, 2009.

Harvestmen, also

called "daddy long-legs" comprise a type (Order Phalangida)

of arachnid that is not a spider (Order Araneida) even though it it is

long-legged and somewhat resembles a spider. The body is oval and

compact, and there isn't the sharp demarcation between body segments

that is seen in spiders.

Harvestman on goldenseal leaf. July 17, 2009.

Here's an thrilling

movie about a harvestman on a goldenseal leaf. I obtained a

copy of the screenplay. In the opening scene

Harvestman stands on the leaf. In the second act,

Harvestman stands

there some more. In the third act Harvestman preens

his foot. In the action-packed finale, a couple

other

harvestpeople appear and they all

walk away. The end. Stephen Spielberg,

eat your heart out!

A reason for seeking out the goldenseal fruits is that earlier this

year I saw the same plants in flower and snapped some pics. Here's what

goldenseal looked like then:

Goldenseal flowering. April 28, 2009. Delaware County, Ohio.

Goldenseal flowers have

3 sepals that fall

as the flower opens (and thus are not visible here). The

flowers lack

petals entirely, and the job of being conspicuous to attract

pollinators is assumed by the stamens!

Here's a late-stage flowering plant, showing the stamens beginning to

fall. Note the apocarpous gynoecium.

Goldenseal, old flower shedding spent stamens.

April 28, 2009. Delaware County, Ohio.

More recent observations ("next")

Earlier observations ("back")

Earlier observations ("back")

|