(Additional content at flickr Photostream and YouTube Channel)

If you have botany questions or comments please email BobK . Thanks!

A Remarkable Little Hornwort

Notothylas orbicularis

Dawes Arboretum in Licking County, Ohio

August 9, 2010 (and August 18 re-visit)

Notothylas orbicularis

Dawes Arboretum in Licking County, Ohio

August 9, 2010 (and August 18 re-visit)

As mentioned in my

guest

post

on

the Ohio

Flora blog, three intrepid botanists took a trip to Dawes

Arboretum in Licking County to catch a glimpse of three-birds orchid, Triphora trianthophora, a

small and unusual woodland plant that blooms for just a few days in

August. On the way to the woods where the birds were

chirping, we passed

by a little patch of disturbed ground where an intriguing native

perennial wildflower grows. This is long-leaved ground-cherry, Physalis longifolia (Solanaceae,

the nightshade family). Ground-cherries are similar to nightshades (Solanum) and tomato (Lycopersicon). They all produce a

fruit

that is a many-seeded berry. However,

Physalis in fruit stands apart by developing a

balloon-like inflated calyx around the fruit. A familiar grocery store Physalis is the tomatillo (P. philadelphica), used to make a

popular Mexican green sauce.

The birds weren't quite fully open yet, and they seem tough to get a good photo of even under the best of circumstances, but at least they hadn't flown away.

Three-birds orchid is a small woodland plant.

August 9, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

Bio-blitzing for Orchids

Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio

August 7-8, 2010

Bio-blitzing for Lichens

Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio

August 7-8, 2010

Shrubbery!

Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve

August 2, 2010

(where perhaps I would have found cave moss if I hadn't stayed so long at the bog.)

Purple Chokeberry

(Aronia or Photinia or Pyrus ...

floribunda or prunifolia or atropupurea or arbutifolia var. atropurpurea)

Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve

August 2, 2010

Long-leaved

ground-cherry

has pendent flowers, and, in fruit, an inflated calyx.

August 9, 2010. Dawes Arboreum, Licking County, Ohio.

August 9, 2010. Dawes Arboreum, Licking County, Ohio.

The birds weren't quite fully open yet, and they seem tough to get a good photo of even under the best of circumstances, but at least they hadn't flown away.

Three-birds orchid is a small woodland plant.

August 9, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

Alongside

the birds we saw a plant in that is much more well

known for its leaves than its flowers or fruits. This is wild leek,

also called

"ramp," Allium tricoccum

(Liliaceae), bearing simple umbels of shiny bead-like black seeds. Wild

leek leaves are

abundant in spring, but they wither by early summer so completely that

they are absent when the flowers appear in July.

Wild leek umbels display shiny black seeds. August 9, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

When we were done birdwatching, we headed back home alongside a soybean field adjacent to the woods. One of us, an especially sharp-eyed person named Jeff (Rosaceae, the rose family), somehow spotted, as he is wont to do, on a patch of bare soil, a green amorphous thing that he immediately reported as possibly being "one of those non-Phaeoceros, non Anthoceros

Hornworts comprise one of the three plant divisions that are collectively, but informally, referred to as “bryophytes.” The “bryophyte” designation is informal because it is now generally accepted that they do not have a common ancestor that is not also shared with another plant group, i.e., they are a "polyphyletic" group. The other “bryophyte” divisions are mosses (Division Bryophyta) of which there are just over 400 species in Ohio, and liverworts (Division Marchantiophyta) with approximately 125 species in Ohio.

Hornworts, Division Anthocerotophyta, are a relatively small group that is mainly tropical. Ohio is home to just three hornworts, all of which are are most often found on disturbed ground, and easily overlooked. Hornworts engage in an amazing symbiosis with a type of bacterium called Nostoc that lives in colonies inside special slime-filled cavities in the hornwort plants. The Nostoc cells have the unusual ability to perform "nitrogen fixation," whereby nitrogen from the air is converted into inorganic dissolved nitrogen (i.e., fertilizer) that is useful to the hornwort.

A more typical hornwort is distinguished by having a sporophyte that is indeed horn-like. A good example is our most frequently encountered species, Phaeoceros laevis (Notothyladaceae), shown below from the fall of 2007 when it was seeen on the disturbed soil of a pipeline cut in Hocking County. The Phaeoceros sporophyte elongates by adding cells at its base through the activities of a growth tissue called a "basal meristem." This is a very unusual manner of growth for plants, which generally get longer by adding cells at their tips, i.e., by having an "apical meristem." See also how the Phaeoceros sporophyte splits at its tip while it matures, releasing spores. Incidentally, Spore color is a useful diagnostic trait separating Phaeoceros from the similar genus Anthoceros, which has dark brown-black spores. hornworts that have tiny sideways sporophytes instead up upright horn-like ones."

A hornwort with horns, Phaeoceros laevis. October 14, 2007 in Hocking County, Ohio.

This is a picture of Jeff’s great find, Notothylas orbicularis (Notothyladcaeae), snapped on a return visit the following week. It looks like it's all gametophyte, but lo, behold there are indeed sporophytes present. They're not horn-like as you'd expect on a hornwort, but are instead little bullet-shaped things laying sideways.

Wild leek umbels display shiny black seeds. August 9, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

When we were done birdwatching, we headed back home alongside a soybean field adjacent to the woods. One of us, an especially sharp-eyed person named Jeff (Rosaceae, the rose family), somehow spotted, as he is wont to do, on a patch of bare soil, a green amorphous thing that he immediately reported as possibly being "one of those non-Phaeoceros, non Anthoceros

Hornworts comprise one of the three plant divisions that are collectively, but informally, referred to as “bryophytes.” The “bryophyte” designation is informal because it is now generally accepted that they do not have a common ancestor that is not also shared with another plant group, i.e., they are a "polyphyletic" group. The other “bryophyte” divisions are mosses (Division Bryophyta) of which there are just over 400 species in Ohio, and liverworts (Division Marchantiophyta) with approximately 125 species in Ohio.

Hornworts, Division Anthocerotophyta, are a relatively small group that is mainly tropical. Ohio is home to just three hornworts, all of which are are most often found on disturbed ground, and easily overlooked. Hornworts engage in an amazing symbiosis with a type of bacterium called Nostoc that lives in colonies inside special slime-filled cavities in the hornwort plants. The Nostoc cells have the unusual ability to perform "nitrogen fixation," whereby nitrogen from the air is converted into inorganic dissolved nitrogen (i.e., fertilizer) that is useful to the hornwort.

A more typical hornwort is distinguished by having a sporophyte that is indeed horn-like. A good example is our most frequently encountered species, Phaeoceros laevis (Notothyladaceae), shown below from the fall of 2007 when it was seeen on the disturbed soil of a pipeline cut in Hocking County. The Phaeoceros sporophyte elongates by adding cells at its base through the activities of a growth tissue called a "basal meristem." This is a very unusual manner of growth for plants, which generally get longer by adding cells at their tips, i.e., by having an "apical meristem." See also how the Phaeoceros sporophyte splits at its tip while it matures, releasing spores. Incidentally, Spore color is a useful diagnostic trait separating Phaeoceros from the similar genus Anthoceros, which has dark brown-black spores. hornworts that have tiny sideways sporophytes instead up upright horn-like ones."

A hornwort with horns, Phaeoceros laevis. October 14, 2007 in Hocking County, Ohio.

This is a picture of Jeff’s great find, Notothylas orbicularis (Notothyladcaeae), snapped on a return visit the following week. It looks like it's all gametophyte, but lo, behold there are indeed sporophytes present. They're not horn-like as you'd expect on a hornwort, but are instead little bullet-shaped things laying sideways.

MOUSEOVER the

image to

see

interpretive LABELS

Notothylas

orbicularis is a

small plant that grows on disturbed soil.

August 18, 2010. Dawes Arboretum. Licking County, Ohio.

In a detailed study of the pollination of both Impatiens species in (the State of) Delaware during the mid-70's, Richard Rust observed that they share the same principal pollinator, a bumblebee Bombus vagrans. This may not be that species, which indeed is common here as well as in Delaware, but indeed here we see a bumblebee visiting the touch-me-not.

August 18, 2010. Dawes Arboretum. Licking County, Ohio.

At the edge of the

woods

between the wort and the beans, there is a nice stand of pale

touch-me-not, Impatiens pallida is a member of an elite class of plants, woodland

annuals, of which there seem not to be very many. Why are there

so few

woodland annuals? Probably because annual plants, with only a short

period of

time in which to do everything

--i.e., sprout from seed, grow into a

flowering plant, make flowers, and set fruit --generally need a lot of

energy input to race along like that. Since shady woodlands are not a

festival of incoming energy, the forest floor is populated mainly by

perennials, not annuals.

(Balsaminaceae). The touch-me-nots, of which there are 2 species on

Ohio, this one and the orange one (Impatiens

capensis).

Pale touch-me-not is a woodland annual.

August 9, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

Pale touch-me-not is a woodland annual.

August 9, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

Here's

a close-up of the touch-me-not blossom. The floral morphology here is a

bit confusing. As is sometimes the case, not all that is showy is

petals. The t-m-n blossom has, to begin with, three sepals two of which

are, as one would expect, small and green, while the third sepal is

expanded and sac-like, with a nectar-filled spur at the back. The

petals are colorful as well, and there are three of them: one petal at

the

top forming the upper lip of the flower, and two petals that are close

together at the bottom, forming a lower lip. The stamens and the stigma

together together form a compound structure at the upper edge of the

flower's throat. The male stamens (5 of them) are fused and into a cap

that covers the female stigma during the initial (male) stage of

flowering, which is pushed off as the ovary elongates, ushering in the

functionally female second phase of the flower's several day life span.

Pale touch-me-not flower.

August 9, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

Pale touch-me-not flower.

August 9, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

In a detailed study of the pollination of both Impatiens species in (the State of) Delaware during the mid-70's, Richard Rust observed that they share the same principal pollinator, a bumblebee Bombus vagrans. This may not be that species, which indeed is common here as well as in Delaware, but indeed here we see a bumblebee visiting the touch-me-not.

Bumbling mumbling bumblebee

humbly

visits

touch-me-not blossom.

Nearby is a dense

stand

of a

robust cryptogam, lady fern, Athyrium

felix-femina

(Dryopteridaceae, the woodfern family). Lady fern is often overlooked

because its frond shape and

dissection type (bipinnate-pinnatifid) makes it look a lot like various

woodferns in the genus Dryopteris.

Lady fern looks sort of woodferny.

August 9, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

Lady fern looks sort of woodferny.

August 9, 2010. Licking County, Ohio.

The best

way to separate the two similar fern genera is by the shape of their

sori. Sori are clusters of sporangia, that are at first covered by a

flap of leafy

tissse called the "indusium." While Dryopteris

sori are kidney-shaped (reniform), those of Athyrium are elongate.

Lady fern sori are elongate.

August 18, 2010. Dawes Arboretum. Licking County, Ohio.

Lady fern sori are elongate.

August 18, 2010. Dawes Arboretum. Licking County, Ohio.

Bio-blitzing for Orchids

Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio

August 7-8, 2010

Orchids are

adorable!

Look

how hard they are trying to be

milkweeds. The poor things will probably never learn that there's

more to being at the pinnacle of phyto-awesomeness than simply packing

pollen grains together into pollinaria to be delivered en masse to

another flower, thus siring all of the seeds in a fruit. See also the

almost sad way they twist themselves upside-down (most orchid flowers

are "resupinate" in that they rotate 180 degrees during development),

in a desperate bid for the attentions of a few peculiar pollinators

that just aren't

that much into them. Plus

they have an inferior ovary. Milkweeds have a superior ovary. Two of

them, actually. Superior is better than inferior. Two ovaries are

better then one.

At the Deep Woods bio-blitz we saw some orchids. Two of them are ladies' tresses, i.e., members of the genus Spiranthes. Ladies's tresses, of which there are 8 species in Ohio, are slender-stemmed plants with mostly basal linear leaves and the infloresence a spirally twisted spike of small white flowers.

This one is narrow-leaved ladies' tresses, Spiranthes vernalis, which despite having a specific epithet that means "spring," actually flowers in late summer. It is one of Ohio's tallest species, and is further distinguished by having a densely pubescent infloresence. (The lip is reported to be yellowish, but that is not evident in this image.) It is growing in a meadow, a habitat that is typical, according to E. Lucy Braun, who, in her magnificent monocots manual (The Monocotyledonae; OSU Press, 1967) tells us it is a species of "dry grassy meadows and prairies, in acid or alkaline soil; southern in range, extending from Florida and east Texas northward on the coastal plain to New England, and in the interior to Ohio and Missouri."

Narrow-leaved ladies's tresses has a densely pubescent inflorescence.

August 7, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

At the Deep Woods bio-blitz we saw some orchids. Two of them are ladies' tresses, i.e., members of the genus Spiranthes. Ladies's tresses, of which there are 8 species in Ohio, are slender-stemmed plants with mostly basal linear leaves and the infloresence a spirally twisted spike of small white flowers.

This one is narrow-leaved ladies' tresses, Spiranthes vernalis, which despite having a specific epithet that means "spring," actually flowers in late summer. It is one of Ohio's tallest species, and is further distinguished by having a densely pubescent infloresence. (The lip is reported to be yellowish, but that is not evident in this image.) It is growing in a meadow, a habitat that is typical, according to E. Lucy Braun, who, in her magnificent monocots manual (The Monocotyledonae; OSU Press, 1967) tells us it is a species of "dry grassy meadows and prairies, in acid or alkaline soil; southern in range, extending from Florida and east Texas northward on the coastal plain to New England, and in the interior to Ohio and Missouri."

Narrow-leaved ladies's tresses has a densely pubescent inflorescence.

August 7, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

Nearby, see another

ladies'

tresses. This, near the opposite end of the Spiranthes size spectrum, is little

ladies' tresses, S. tuberosa.

E. Lucy reports that this is "distinguished from other species by its

very slender stem with very slender spirally twisted glabrous spike of

small flowers (perianth 2-3 mm long)." This orchid could be mistaken

for another little one, slender ladies' tresses, S. gracilis, but that species is

marked by a prominent green blotch on the lip that is absent from this

pure-white beauty.

Little ladies' tresses. August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve.

Little ladies' tresses. August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve.

If you look really

carefully

just above the lowermost blossom there is what appears to be a little

spider.

Spider on Spiranthes,

perhaps? August 7, 2010. Deep Woods

Preserve. Hocking County, Ohio.

Nearby in the

meadow on

a

willow shrub there is a magnificent caterpillar, the larva of a

cecropia moth. Hyalophora cecropia.

The cecropia is North America's largest native moth, a member of the

Saturniidae family, or giant silk moths. A very nice step-by step

description of the development of a cecropia moth, presented by silk

enthusiast Michael Cook, can be seen here.

Cecropia moth larva on willow in meadow at Deep Woods. August 7, 2010.

On the gravel parking spot, an immature field cricket in the difficult genus Gryllus appeared along with a passing sowbug, a type of isopod crustacean. Pillbugs (affectionately termed a"roly-polys" because of their armadillo-like habit of rolling up when disturbed) and sowbugs (which are similar, but without the rolling-up trick) are our only terrestrial crustaceans. Our most common pillbugs and sowbug species are introduced ones from the Old World.

Cricket and sowbug pass one another like ships in the night.

August 8, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve. Hockiing County, Ohio.

Cecropia moth larva on willow in meadow at Deep Woods. August 7, 2010.

Several years ago a

newly-emerged cecropia moth appeared at the OSU-Marion Campus Prairie.

Newly-emerged cecropia moth. May 17, 2006. Marion County, Ohio.

Newly-emerged cecropia moth. May 17, 2006. Marion County, Ohio.

The bio-blitz is an

overnight event, and the entomologists were hard at work after dark,

trapping

moths with lights. I snapped a picture of one resting on a wall near

their light, and was later surprised and delighted to learn it's a very

famous moth that I hadn't realized occurred occurred here, not just

in Britain.

This is Biston betularia, a moth that is a textbook example of natural selection of a type called "industrial melanism" wherein a prevalence of dark forms develops in response to air pollution. In merry old England, the moth occurs in two color forms: gray-speckeled and black (melanic). When merry old smoke killed the merry old lichens on the merry old trees and made the merry old bark dark instead of gray-speckled with lichens, the frequency of the dark moths was observed to increase because (and it was demonstrated) they were more well hidden from predation by birds while resting on the dark bark.

The pepper moth is an icon of evolution. (That's a good thing, Jonathan Wells.)

Augusgt 8, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

This is Biston betularia, a moth that is a textbook example of natural selection of a type called "industrial melanism" wherein a prevalence of dark forms develops in response to air pollution. In merry old England, the moth occurs in two color forms: gray-speckeled and black (melanic). When merry old smoke killed the merry old lichens on the merry old trees and made the merry old bark dark instead of gray-speckled with lichens, the frequency of the dark moths was observed to increase because (and it was demonstrated) they were more well hidden from predation by birds while resting on the dark bark.

The pepper moth is an icon of evolution. (That's a good thing, Jonathan Wells.)

Augusgt 8, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

On the gravel parking spot, an immature field cricket in the difficult genus Gryllus appeared along with a passing sowbug, a type of isopod crustacean. Pillbugs (affectionately termed a"roly-polys" because of their armadillo-like habit of rolling up when disturbed) and sowbugs (which are similar, but without the rolling-up trick) are our only terrestrial crustaceans. Our most common pillbugs and sowbug species are introduced ones from the Old World.

Cricket and sowbug pass one another like ships in the night.

August 8, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve. Hockiing County, Ohio.

On a nearby grass

culm,

a

female short-winged meadow katydid, Conocephalus

brevipennis

listens for the faint and extremely high-pitched (10 to 20 kHz...forget

about this one, baby-boomers!) song of a potential mate.

Short-winged meadow katydids are numerous and widespread in the east.

August 8, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve. Hocking County, Ohio.

Short-winged meadow katydids are numerous and widespread in the east.

August 8, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve. Hocking County, Ohio.

The following day

we saw

additional interesting plants, including two woodland orchids. One is a

widely distributed species of "rattlesnake-plantain," Goodyera pubescens. The flowers,

arranged in a dense spike, are small, greenish, and have a sac-like

appearance.

Downy rattlesnake-plantain. August 8, 2010.

Downy rattlesnake-plantain. August 8, 2010.

A unique

rattlesnake-plantain

feature is the basal rosette of evergreen leaves bearing a beautiful

pattern of silvery-white reticulations.

Rattlesnake-plantain leaves are evergreen, and silvery-reticulate patterned.

(Photo taken August, 2006.)

Rattlesnake-plantain leaves are evergreen, and silvery-reticulate patterned.

(Photo taken August, 2006.)

The

other woodland orchid is one much less frequently encountered, but also

with a snake theme in its common name: green adder's-mouth, Malaxis unifolia. This

is our only species in a genus of small tiny-flowered orchids. It is

said to occur in a wide range of moisture conditions, from bogs to

dryish oak woods, apparently confined to acid substrates.

Green adder's-mouth bears a single oval leaf at its middle.

August 8, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio.

Green adder's-mouth bears a single oval leaf at its middle.

August 8, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio.

Here's a closer

view of

the Malaxis inflorescence. It

seems

like one flower has been pollinated,

perhaps quite some time ago, as it is well along the way to becoming a

fruit.

Green adder's-mouth flowers are tiny.

August 8., 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

Green adder's-mouth flowers are tiny.

August 8., 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

On the way back

from the

woods, we were pleased to encounter two species of milkworts (genus Polygala,

family Polygalaceae). These plants produce numerous small flowers

presented in a dense head-like raceme. The most conspicuous parts of

the flowers are two sepals that are enlarged and petaloid and often

obscure the view of the other flower parts: 3 smaller sepals, and 3

small petals fused to a column of stamens, and a pistil that matures

into a small capsule. The showier one is field milkwort, Polygala sanguinea; the slender

pale-flowered one is whorled milkwort, P. verticillata. Both are annuals.

Milkwort (Polygala) species at Deep Woods. August 8., 2010.

Left: field milkwort. Right: whorled milkwort.

Milkwort (Polygala) species at Deep Woods. August 8., 2010.

Left: field milkwort. Right: whorled milkwort.

Another quite

slender

annual

herb of open sandy ground and dry fields is a type of St. John's-wort called "orange-grass" or

"pineweed," Hypericum gentianoides.

Orange-grass is a very slender annual of open sites.

August 8, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

Seedbox produces 4-merous yellow flowers. August 8, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

Orange-grass is a very slender annual of open sites.

August 8, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

In a damp

depression

grows

seedbox, Ludwigia alternifolia (Onagraceae,

the evening-primrose family). This is an an erect branched perennial

with 4-petaled flowers and an inferior ovary that eventually develops

into a squarish capsule.

Seedbox produces 4-merous yellow flowers. August 8, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

Bio-blitzing for Lichens

Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio

August 7-8, 2010

Once a year,

enthusiastic

naturalists gather at Deep Woods Preserve, a

privately owned nature sanctuary in Hocking County, to tally as many

species as possible during a 24-hour period. This annual "bio-blitz" is

part of the Deep Woods All-Taxa-Biotic Inventory (ATBI). This year, for

a change of pace from bryophytes, I tried my hand (lens) at lichens.

Ohio's largest genus of macrolichens is Cladonia, a diverse group of fruticose (shrubby) ones that occur most often on the ground. The most well known cladonia, arguably the best known of all lichens and one of the few having a widely accepted common name, is "British soldiers," Cladonia cristatella. This is a very colorful, fairly pollution-tolerant species distinguished by its large red apothecia perched atop the upward extending "podetia."

British soldier lichen looking eerlily tree-like over an alien landscape.

August 7, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

Ohio's largest genus of macrolichens is Cladonia, a diverse group of fruticose (shrubby) ones that occur most often on the ground. The most well known cladonia, arguably the best known of all lichens and one of the few having a widely accepted common name, is "British soldiers," Cladonia cristatella. This is a very colorful, fairly pollution-tolerant species distinguished by its large red apothecia perched atop the upward extending "podetia."

British soldier lichen looking eerlily tree-like over an alien landscape.

August 7, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

Another blunt

cladonia,

tipped with even larger apothecia than

those of British soldiers, is Ohio's most common brown-fruited species,

turban lichen, Cladonia pezizaformis.

The huge apothecia spill over, turbanlike, onto the twisted,

fissured

podetia.

Turban lichen apothecia spill over onto the podetia.

August 6, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

The podetia of some cladonias end in cups. Many of them are confusing to identify; here's one that's distinctive. It's ladder lichen, C. cervicornis. This species bears 2-4 tiers of cups, often with dissected margins tipped with tiny apothecia, each cup each arising from the center of the one below. Ladder lichen is widely distributed in northeastern U.S., and is common in Ohio as an "old field" species on the ground. In their terrific manual "The Macrolichens of Ohio," (Ohio Biological Survey, 2004) Ray Showman and Don Flenniken tell us this species is also common in unreclaimed stripmines.

Ladder lichen is a tiered cup-former that proliferates from the centers of the cups.

(Note also a bit of lipstick powderhorn, Cladonia macilenta, in upper right area of photo.)

August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio.

Turban lichen apothecia spill over onto the podetia.

August 6, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

The podetia of some cladonias end in cups. Many of them are confusing to identify; here's one that's distinctive. It's ladder lichen, C. cervicornis. This species bears 2-4 tiers of cups, often with dissected margins tipped with tiny apothecia, each cup each arising from the center of the one below. Ladder lichen is widely distributed in northeastern U.S., and is common in Ohio as an "old field" species on the ground. In their terrific manual "The Macrolichens of Ohio," (Ohio Biological Survey, 2004) Ray Showman and Don Flenniken tell us this species is also common in unreclaimed stripmines.

Ladder lichen is a tiered cup-former that proliferates from the centers of the cups.

(Note also a bit of lipstick powderhorn, Cladonia macilenta, in upper right area of photo.)

August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio.

Alongside the

ladder

lichen

is one that, by virtue of its red apothecia atop elongate podetia, is

somewhat reminiscent of British soldiers, but with a tiny red cap. This

one, called

"lipstick powderhorn," Cladonia

macilenta, is widespread across much of North America, and

is scattered and fairly common in Ohio, occurring on bark or soil. Its

squamules (the flakey portion of the lichen at its base) as well as the

upright podetia, are covered with fine soredia --minute speherical

bodies that consist of a few algal cells enclosed by fungal strands.

The soredia

slough off and can develop into new lichens, constituting a principal

means by which many lichen reproduce.

Lipstick powderhorn podetia are mealy-sorediate and may be tipped with small red apothecium.

August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio.

Lipstick powderhorn podetia are mealy-sorediate and may be tipped with small red apothecium.

August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio.

Cup-forming

cladonias

can be

difficult to identify. This one with closed cups

distorted by marginal proliferations seems to match

descriptions for "mixed-up pixie-cup," Cladonia mateocyatha,

a species that is uncommon in Ohio. Endemic to the the southeastern

U.S., this generally Appalachian and Ozark species occurs on thin sandy

soil or rocks in open areas.

Mixed-up pixie-cup bears apothecia along marginal proliferations.

August 7, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

Alongside the pixie-cup is a Cladonia species with a wholly different aspect. This is one of the "reindeer lichens," tangled lichens with a fibrous outer surface. (Confusion alert: reindeer lichens were for a long time considered members of the genus Cladonia, but then they got placed in their own genus Cladina. More recently, they got placed back into Cladonia.) We have 3 species of reindeer lichen in Ohio, distinguished by their color, branching patterns and chemistry. This one, by virtue of its ashy-white color and tendency to form branches in whorls of three or four, seems to be gray reindeer lichen, C. rangiferina. Showman and Flenniken tell is that this lichen's general distribution "...is Applachian-Boreal; rather common in southern counties of Ohio, on soil almost exclusively, often among mosses. A common component of the "lichen-ericad" association at the top of sandstone cliffs in southeastern Ohio." ("An "ericad" is a member of the heath family, Ericaceae, which consists largely of low shrus with a strong fidelity to acidic-soil sites.)

Gray reindeer lichen and mixed pixie-cup.

August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve. Hocking County, Ohio, USA.

Mixed-up pixie-cup bears apothecia along marginal proliferations.

August 7, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

Alongside the pixie-cup is a Cladonia species with a wholly different aspect. This is one of the "reindeer lichens," tangled lichens with a fibrous outer surface. (Confusion alert: reindeer lichens were for a long time considered members of the genus Cladonia, but then they got placed in their own genus Cladina. More recently, they got placed back into Cladonia.) We have 3 species of reindeer lichen in Ohio, distinguished by their color, branching patterns and chemistry. This one, by virtue of its ashy-white color and tendency to form branches in whorls of three or four, seems to be gray reindeer lichen, C. rangiferina. Showman and Flenniken tell is that this lichen's general distribution "...is Applachian-Boreal; rather common in southern counties of Ohio, on soil almost exclusively, often among mosses. A common component of the "lichen-ericad" association at the top of sandstone cliffs in southeastern Ohio." ("An "ericad" is a member of the heath family, Ericaceae, which consists largely of low shrus with a strong fidelity to acidic-soil sites.)

Gray reindeer lichen and mixed pixie-cup.

August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve. Hocking County, Ohio, USA.

Another reindeer

lichen,

"Dixie reindeer lichen," Cladonia

subtenuis,

is slightly less ashy-colord (more of a yellow-green), and produces

branches

dichotomously (i.e., in twos). This, the most common reindeer lichen in

Ohio, is quite common across much of the southern half of the state.

Here's Dixie reindeer lichen with Ohio haircap moss, Polytrichum

ohioense on this soil over sandstone in an open area.

Dixie reindeer lichen and Ohio haircap moss. August 7, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

Dixie reindeer lichen and Ohio haircap moss. August 7, 2010. Hocking County, Ohio.

Some intriguing

non-lichenized fungi are here today. One of them is what has

been descibed as

"by far the most common of the coral mushrooms...--except that, it's

not, taxonomically speaking, a "coral mushroom," because it's placed

with the jelly fungi by virtue of a microscopic feature (the presence

of cross-walls on the spore-producing basidia). This is "false

coral mushroom," Tremellodendron

pallidum, which occurs in the ground

under hardwoods.

False coral mushroom grows in the ground. August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve.

False coral mushroom grows in the ground. August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve.

Here's

a mushroom. By virture

of (1) its pale gills separate from the stem and white spore print (not

evident in the photo), (2) the swollen base and remnants on the

stem of a "universal veil" that surrounded the entire mushroom

when it was tiny, and (3) a drooping skirt-like ring high on the stem

that is a remnant of the "partial veil" that covered the gills at an

intermediate stage of development, it is clear we have an Amanita.

Probable Amanita cokeri at Deep Woods.

Note swollen and scaly base, pointed scales on top.

Probable Amanita cokeri at Deep Woods.

Note swollen and scaly base, pointed scales on top.

The white color and

prominent

scales both on the swollen base and, especially, atop the cap point to Amanita cokeri.

Prominent triangular pointed scales atop Amanita cokeri.

(This looks like an uncomfortable place for a toad to sit!)

August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio.

Prominent triangular pointed scales atop Amanita cokeri.

(This looks like an uncomfortable place for a toad to sit!)

August 7, 2010. Deep Woods Preserve, Hocking County, Ohio.

Shrubbery!

Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve

August 2, 2010

On my way to this

beautiful

place where I searched in vain for "cave moss,"

Nelson Ledges State Park, Portage County,

Ohio,

(where perhaps I would have found cave moss if I hadn't stayed so long at the bog.)

...I stopped at

what is correctly

described

as "one of the finest and least disturbed sphagnum kettle-hole bogs in

Ohio," Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve. Bogs are home to a

number of interesting shrubs, some of which have a rather strict

fidelity to such sites. One of these is leatherleaf, Chamaeaphne calyculata which might

by more aptly called "the leatherleaf " because it's the only species

in its genus. The leatherleaf occurs in bogs across boreal North

America and extends south into parts of the eastern U.S. It also occurs

in Asia.

The leatherleaf is an evergreen bog shrub. August 2, 2010.

Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve. Portage County, Ohio.

Swamp loosestrife is an arching, almost vine-like wetland herb.

Triangle Lake Bog, Portage County, Ohio. August 2, 2010.

The leatherleaf is an evergreen bog shrub. August 2, 2010.

Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve. Portage County, Ohio.

The

heath family is noted for

its association with acid soil, so it's not unexpected to see

additional representatives at the bog. Here's high-bush

blueberry, Vaccinium corymbosum,

Ohio's only member of the sub-set of the genus that generally grows in

excess of one meter tall. Although most members of the heath family

have

flowers that are hypogynous with a superior ovary, those of Vaccinium and just a few two other

Ohio genera (the huckleberry genus Gaylussacia

and the wintergreen genus Gaultheria)

are epigynous, with an inferior ovary. This is easily seen by looking

at the fruit, which sports 5 distinct sepals on top.

While cranberry is a shrub that seems like

more a

wildlfower, swamp

loosestrife, Decodon verticillatus (the

only member of its genus, in the loosestrife family, Lythracae) is a

remarkably shrub-like herb described as being "somewhat woody

at base." It grows arched over the water, and when it dips back into

the aqua pura its submersed

parts develop a spongy-corky tissue with air spaces,

termed "aerenchyma," from which issue forth adventitious roots, and the

continuation of the stem.

High-bush

blueberry

demonstrates its inferior ovary.

Triangle Lake Bog State nature preserve, Portage County, Ohio. August 2, 2010.

Triangle Lake Bog State nature preserve, Portage County, Ohio. August 2, 2010.

Another Vaccinium, but with a wholly

different aspect, is large cranberry, V.

macrocarpon. It's

a low trailing evergreen shrub. This photo, taken about this time

several years ago, displays well the diagnostic trait that

distinguishes

it from small cranberry (V. oxycoccus):

a pair of leaf-like bracts inserted above the middle of the pedicel

(arrow). Small cranberry would bear smaller scale-like ones, situated

lower

on the pedicel.

Large cranberry is a trailing evergreen shrub.

Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve. July 28. 2007.

Large cranberry is a trailing evergreen shrub.

Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve. July 28. 2007.

Swamp loosestrife is an arching, almost vine-like wetland herb.

Triangle Lake Bog, Portage County, Ohio. August 2, 2010.

Even though they

both

contain

the same causative agent, the non-volatile oil urushiol, poison-sumac, Toxicodendron vernix (Anacardiaceae,

the cashew family), a rare shrub found only in swamps and bogs, is

reportedly a much more poisonous plant than its ubiquitous congenor

poison-ivy

(T. radicans).

Poison-sumac bears alternately arranged, pinnately compound, leaves.

August 2, 2010. Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve.

Poison-sumac bears alternately arranged, pinnately compound, leaves.

August 2, 2010. Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve.

A much more common

wetland

shrub, with the added benefit of being safe to touch, is

buttonbush, Cephalanthus occidentalis.

Buttonbush is a member of the Rubiaceae, the madder family.

I'm not sure what it's so mad about; this is a huge (the fourth

largest!) family, cosmopolitan but most

diverse in the tropics. Plus, it's the coffee family! Our other members

are all small herbs, such as

bluets (Houstonia and Hedyotis), partridge-berry (Mitchella repens ) and

cleavers/bedstraw (Galium).

The flowers are 4-merous, with an inferior ovary, and fused petals.

Buttonbush is a swamp shrub that bears globose heads of small white flowers.

August 2, 2010. Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve.

Buttonbush is attractive to a great variety of incects. In his great book about the importance of using native species in landscape plantings called "Bringing Nature Home," Douglas W. Tallamy has nice things to say about buttonbush. He describes the flowers as "wonderful nectar sources for butterflies in midsummer," and asserts that if you plant it, you may attract the beautiful larve of something called the the smeared dagger moth (Acronicta oblinita).

Here we see a bumblebee at the bog, a likely pollinator, sipping nectar.

A buttonbee forages on bumblebush, or something to that effect.

Buttonbush is a swamp shrub that bears globose heads of small white flowers.

August 2, 2010. Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve.

Cephalanthus is is mainly

opposite-eaved, but also bears leaves in whorls of three, a distinctive

and unusual trait.

Buttonbush often bears leaves in whorls of three.

Buttonbush often bears leaves in whorls of three.

Buttonbush is attractive to a great variety of incects. In his great book about the importance of using native species in landscape plantings called "Bringing Nature Home," Douglas W. Tallamy has nice things to say about buttonbush. He describes the flowers as "wonderful nectar sources for butterflies in midsummer," and asserts that if you plant it, you may attract the beautiful larve of something called the the smeared dagger moth (Acronicta oblinita).

Here we see a bumblebee at the bog, a likely pollinator, sipping nectar.

A buttonbee forages on bumblebush, or something to that effect.

Steeplebush, Spiraea tomentosa

is a wand-shaped shrub in the rose family (Rosaceae). It's also

sometimes called "hardhack," because its stems are tough. (How tough

can they be, I wonder?) An indicator

of high-quality wetlands, this pink-flowered spiraea with leaves that

are densely wooly (tomentose) beneath is less common than its

white-flowered, smooth-leaved congenor S. alba (meadow-sweet).

Steeplebush is a wand-like wetland shrub.

August 2, 2010. Triangle Lake Bog. Portage County, Ohio.

Steeplebush is a wand-like wetland shrub.

August 2, 2010. Triangle Lake Bog. Portage County, Ohio.

It's not a shrub.

It's

not

even a shrubby (fruticose) lichen, but it's growing on a shrub. This is

one

of the most common foliose lichens, hammered shield lichen, Parmelia sulcata. Note the large

size, patterned ridges on lobes, powdery patches of soredia, and a dark

undersurface.

Hammered shield lichen at Triangle Lake Bog. August 2, 201.

Hammered shield lichen at Triangle Lake Bog. August 2, 201.

Purple Chokeberry

(Aronia or Photinia or Pyrus ...

floribunda or prunifolia or atropupurea or arbutifolia var. atropurpurea)

Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve

August 2, 2010

On the way to this

beautiful

place where I searched in vain for "cave moss,"

Nelson Ledges State Park, Portage County, Ohio,

(where perhaps I would have found cave moss if I hadn't stayed so long at the bog.)

...I stopped at what is correctly described as "one of the finest and least disturbed sphagnum kettle-hole bogs in Ohio. This is Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve.

Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve. Portage County, Ohio. August 2, 2010.

Nelson Ledges State Park, Portage County, Ohio,

(where perhaps I would have found cave moss if I hadn't stayed so long at the bog.)

...I stopped at what is correctly described as "one of the finest and least disturbed sphagnum kettle-hole bogs in Ohio. This is Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve.

Triangle Lake Bog State Nature Preserve. Portage County, Ohio. August 2, 2010.

It's nice to see

tamarack, or

eastern larch, trees, Larix laricina

(Pinaceae). Tamarack is a deciduous conifer of northern regions, found

this far south only as a glacial relict in bogs.

Tamarack is a distinctive deciduous conifer.

Triangle Lake Bog State Naturee Preserve. Portage County, Ohio. August 2, 2010.

Tamarack is a distinctive deciduous conifer.

Triangle Lake Bog State Naturee Preserve. Portage County, Ohio. August 2, 2010.

The bog mat

surrounding

the

kettle-hole lake is home to a number of interesting shrubs. One of them

is a chokeberry, a plant that is readily distinguished, albeit

only to genus, by pecular scale-like glands scattered along the upper

mid-rib of its leaves.

Chokeberry leaves are marked by tiny scale-like glands along the midvein.

Chokeberry leaves are marked by tiny scale-like glands along the midvein.

Here's the whole

plant.

The

chokeberries (not to be confused with choke-cherry, another somewhat

astringent-fruited member of the rose family, but in its drupe-forming

section), are among the members of the rose family that produce the

unique fruit type known as a "pome." (I think that I will never see, a

pome as lovely as a tree.) This group also includes apple and crabapple

(Malus), pear (Pyrus) hawthorn (Crataegus), and mountain-ash (Sorbus).

At various times, and according to various treatments, chokeberry has

been "submerged" along with one or more other genera, in an especially

large version of the genus Pyrus.

Currently, it seems, the

chokeberries now enjoy a separate status in their own genus, Photinia.

Chokeberry at Triangle Lake Bog. August 2, 2010.

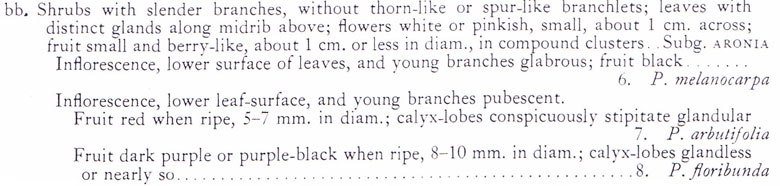

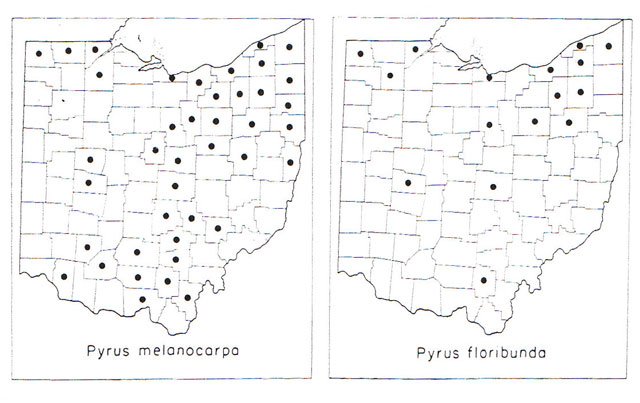

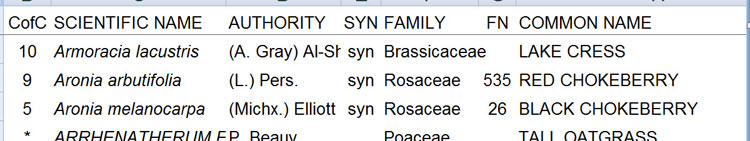

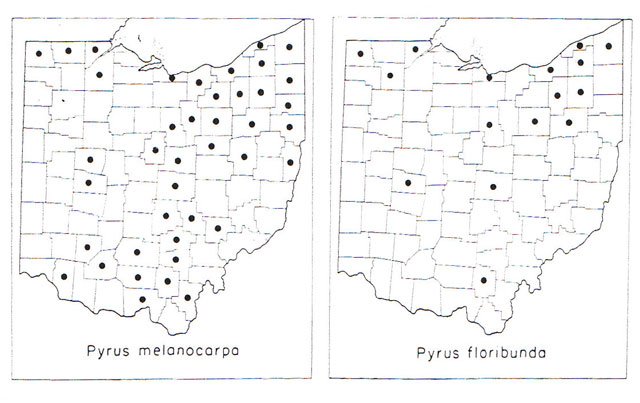

But what species of chokeberry? Traditionally, as reflected in E. Lucy Braun's "Woody Plants of Ohio" (OSU Press, originally published in 1961), botanical manuals have listed three species of chokeberry in our general region: (1) black chokeberry, AroniaPyrus) melanocarpa, the most widely distributed speicies in Ohio, (2) purple chokeberry, Aronia (Pyrus) prunifolia or floribunda, which is more local and northerly distributed here, and (3) red chokeberry, Aronia (Pyrus) arbutifolia, an eastern species long believed not to occur in Ohio.

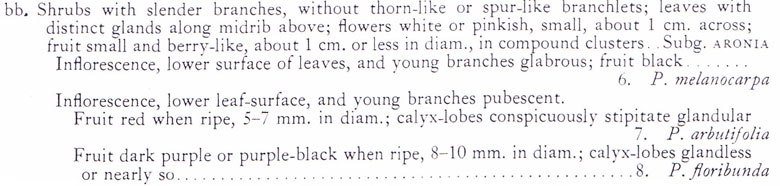

To wit, here's the chokeberry part of E.'s Pyrus key:

Chokeberry in Ohio, from E. Lucy Braun's 1961 book, "The Woody Plants of Ohio."

Close scrutiny of the photo above shows some diagnostic features that point to (so-called) Pyrus floribunda (purple chokeberry): (1) the fruit are red-purple (not black), and, (2) zooming in, we see substantial pubescence on the lower leaf surfaces.

(k

(k

Zoom-crop of chokeberry leaf showing pubescence.

Indeed, in a excellent

study published in 1990 (link to .pdf) entitled "The vegetation of

three Sphagnum-dominated

basin-type bogs in northeastern Ohio," (OHIO

J. SCI. 90 (3): 54-66, 1990), Dr. Barbara Andreas listed Aronia prunifolia

as the chokeberry present at this site. However, in the definitive

plant species list for Ohio, the spreadsheet appendix to the Ohio EPA's

2004 publication "Floristic Quality Assessment Index (FQAI) for

Vascular Plants and Mosses for the State of Ohio," also by Dr. Andreas,

along with John Mack and James McCormac, we see no entry for purple

chokeberry (but a surprising entry for red chokeberry, with a very high

"coefficient of conservatism," suggesting that some bona fide Ohio stations were

ultimately discovered!).

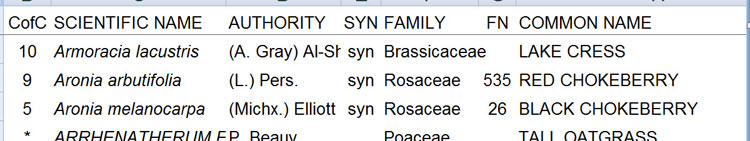

Ohio chokeberries in the FQAI.

Chokeberry at Triangle Lake Bog. August 2, 2010.

But what species of chokeberry? Traditionally, as reflected in E. Lucy Braun's "Woody Plants of Ohio" (OSU Press, originally published in 1961), botanical manuals have listed three species of chokeberry in our general region: (1) black chokeberry, AroniaPyrus) melanocarpa, the most widely distributed speicies in Ohio, (2) purple chokeberry, Aronia (Pyrus) prunifolia or floribunda, which is more local and northerly distributed here, and (3) red chokeberry, Aronia (Pyrus) arbutifolia, an eastern species long believed not to occur in Ohio.

To wit, here's the chokeberry part of E.'s Pyrus key:

Chokeberry in the

key

of E.

...and here are her maps for the two (then

recognized) Ohio

species.

Chokeberry in Ohio, from E. Lucy Braun's 1961 book, "The Woody Plants of Ohio."

Close scrutiny of the photo above shows some diagnostic features that point to (so-called) Pyrus floribunda (purple chokeberry): (1) the fruit are red-purple (not black), and, (2) zooming in, we see substantial pubescence on the lower leaf surfaces.

(k

(kZoom-crop of chokeberry leaf showing pubescence.

Ohio chokeberries in the FQAI.

The note #26

referenced

in

the "FN" column says that we should "see text p. 263 in Gleason &

Cronquist (1991) regardjng A.

prunifolia (Marshall)

Rehder (Pyrus floribunda

(Lindl.) Spach, Photinia floribunda

(Lindl.) K.R. Robertson & J.B." Here it is:

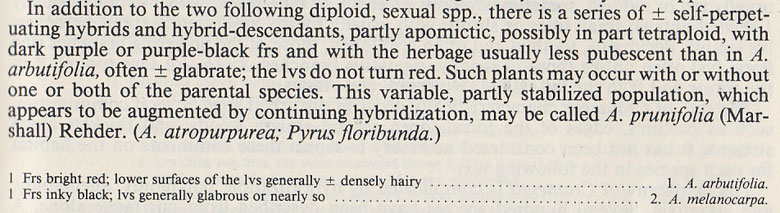

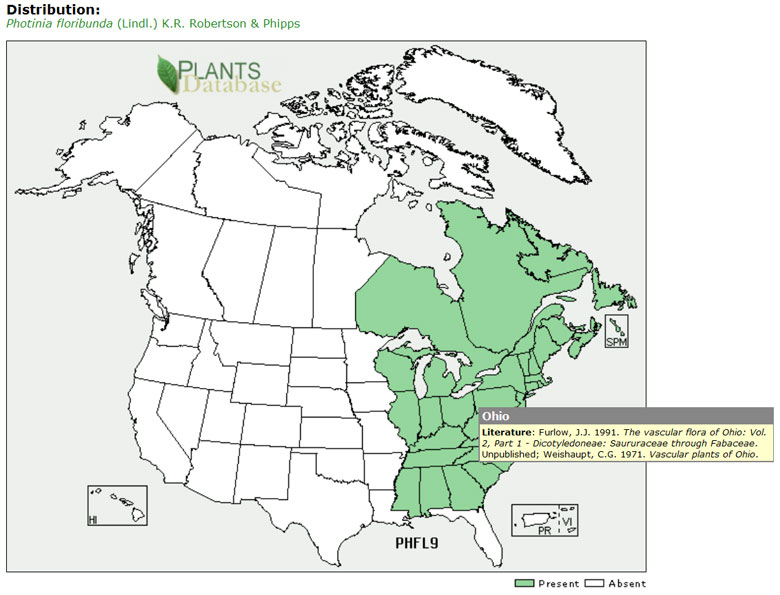

Gleason and

Cronquist

(1991) describe purple chokeberry as a series of hybrids.

That's indeed

interesting,

albeit problematic if you want to put a good species name on a

specimen. Also, it seems not to be the current view of the taxon, at

least insofar as the naming is concerned. The authoritative USDA NRCS

database includes a page for Photinia

floribunda,

showing a wide distribution across the eastern half of North America

that includes Ohio, and two literature citations (one of which is

unpublished, an unfortunate fact that has furrowed many a brow). So

perhaps purple chokeberry is a good species after all. Yay!

Purple chokeberry

on

the

USDA NRCA web site: a good species!