(Additional content at flickr Photostream and YouTube Channel)

If you have botany questions or comments please email BobK . Thanks!

July 31, 2010

Delaware, Ohio

Along State Route 315 in

Delaware, Ohio is a nursery that apparently occupies a larger

tract of land than needed for their commercial plant-growing purposes,

so they planted a nice assemblage of native

and

almost-native prairie species there for us to enjoy as we travel that

pleasant road. One of them is compassplant, Silphium laciniatum

(Asteraceae), a huge, dramatic, and long-lived perennial that, while a

signature element of tallgrass prairie in much of the midwest, might

not

be native this far east. (The single putative Ohio compassplant

station, in the far

south-centrally located Lawrence County, has a history suggestive of an

accidental introduction. We do, however, have oodles of prairie

dock, S. terebinthinaceum, which is just as

good.)

9

Compassplant thrives in a roadside prairie garden.

July 31, 2010. delaware, Ohio.

Compassplant thrives in a roadside prairie garden.

July 31, 2010. delaware, Ohio.

Silphium

is unique among our

"composites," as members of the aster family are often called. Like all

composites, their flowers are small and aggregated together into heads

that simulate individual blossoms and, also like many composites, Silphium flowers are of two types:

(1) radially symmetric ones in the center of each head ("disk

flowers"), and (2) strap-shaped ones encirceling the periphery ("ray

flowers") that act like the petals of more typical flowers (advertising

for pollinators). The

unique Silphium trait is that

the central flowers do not produce fruit. Only the ray flowers are

fertile, the

reverse of the situation found in many composites with otherwise

similar flower heads. Moreover, those central flowers each have a long

horn-like unbranched style very different from the "rabbit-ears" style

banches of, say, a sunflower (Helianthus).

Compassplant disk flowers each bear a long unbranched style. July 31, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.

Compassplant disk flowers each bear a long unbranched style. July 31, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.

While flowers are nice,

it's

actually the leaves of compass plant that receive the most attention,

and gave the plant its common name as it may have helped

direct midwestern settlers and hunters during night-time travel. The

leaves

are oriented in a north-south direction (i.e., with the

blades facing east and west), a stance that has been demonstrated to

result in an optimal photosynthetic rate and water use efficiency,

mainly

by reducing water loss that that would result from a direct

exposure to the sun during the hours of mid-day. Also, the leaves are

beautifully deeply cut, i.e., "laciniate," hence the

specific epithet laciniatum.

Compassplant leaves, photo taken facing west. Note also side-oats grama grass.

July 31, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.

Compassplant leaves, photo taken facing west. Note also side-oats grama grass.

July 31, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.

Another striking prairie

plant is a moderately low-growing grass, side-oats grama, Bouteloua curtipendula. While this

plant is a denizen of prairies and dry hills across much of the U.S.,

and indeed does occur naturally at scattered locations in west-central

Ohio,

it is a common component of prairie restoration seed mixes, and its

presence here is no doubt deliberate. Bouteloua

has a distinctive growth form, consisting of a narrow panicle of many

drooping short spikes, disposed along on one side of the culm (secund).

Here's a closer view of side-oats grama, showing the spike composition.

Side-oats grama spikes are numerous, drooping, and secund.

Delaware, Ohio. July 31, 2010.

Occuring naturally along this road is a thriving population of an attractive wildflower, nodding wild onion, Allium cernuum (traditionally placed in the Liliaceae, now re-classified into a smaller new family, Alliaceae). While Allium is a huge genus containing approx. 500 species worldwide, there just three species native to Ohio. In addition to this nodding one, we have wild garlic (A. canadense), and wild leek (also called "ramps," A. tricoccum). Nodding wild onion is frequent in the calcareous soil of gravel banks, rock ledges, roadsides and praires, where it is often very abundant.

Nodding wild onion with a nodding wild bumblebee.

July 31, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.

Here's a closer view of side-oats grama, showing the spike composition.

Side-oats grama spikes are numerous, drooping, and secund.

Delaware, Ohio. July 31, 2010.

Occuring naturally along this road is a thriving population of an attractive wildflower, nodding wild onion, Allium cernuum (traditionally placed in the Liliaceae, now re-classified into a smaller new family, Alliaceae). While Allium is a huge genus containing approx. 500 species worldwide, there just three species native to Ohio. In addition to this nodding one, we have wild garlic (A. canadense), and wild leek (also called "ramps," A. tricoccum). Nodding wild onion is frequent in the calcareous soil of gravel banks, rock ledges, roadsides and praires, where it is often very abundant.

Nodding wild onion with a nodding wild bumblebee.

July 31, 2010. Delaware, Ohio.

Bumblebees seem to love

it.

Bumblebees visit

nodding

wild onion.

Switchgrass Flowers

July 31, 2010

Columbus, Ohio

Prairie enthusiasts from

sea

to shining sea did a double-take when President George W. Bush

mentioned switchgrass in the 2006 State of the Union address.

Swichgrass at the SOTU.

Indeed, this hardy warm-season grass, especially productive even on marginal sites, is being developed as a bio-energy crop, mainly for the production of ethanol. Because it is a naturally occuring species that now has "cultivar" genotypes which might have ecological properties different than those in the native populations, researchers at the Ohio State University are hard at work investigating the potential for gene flow from the cultivated plants to native prairies. Today I visited a test plot where a variety of switchgrass plants are being grown for gene flow experiments, and saw that some of the plants are in flower.

Switchgass (Panicum virgatum) flowers, like those of all grasses, are tiny. The perianth (sepals and petals) are reduced to two tiny swellings that push open a little pair of leaf-like bracts (a lemma and a palea) that enclose the sexual parts of the flower. Being wind-pollinated, grass flowers lack showy parts. The pollen-producing anthers are pendent, held by slender flexible filaments that enable the pollen to be cast into the breeze. Plumose stigmas serve as excellent wind-borne pollen-snaggers.

Switchgrass in flower. July 31, 2010. Columbus, Ohio.

The peculiar arrangement

of

flowers in the grass family (i.e., its inflorescence type), is called a

"spikelet" (a little spike). In the photo above, we see 7

spikelets, each of which is one-flowered (actually 2-flowered, but one

of the lemma-palea pairs in each spikelet is empty). The spikelets of Panicum, seemingly true to the

name, but probably a coincidence because "Panicum" is just an ancient

name for a type of millet, are

arranged in a diffuse, several-times-brached cluster called a

"panicle."

Here's a picture of switchgrass several years ago, showing its overall aspect.

Swichgrass spikelets are arranged in a diffuse panicle.

July 23, 2007. Larry R. Yoder Prairie at OSU-Marion, Marion County, Ohio.

Here's a picture of switchgrass several years ago, showing its overall aspect.

Swichgrass spikelets are arranged in a diffuse panicle.

July 23, 2007. Larry R. Yoder Prairie at OSU-Marion, Marion County, Ohio.

Somewhat Similar Scirpus Sedges

(some sans sessile spikelets)

Scirpus pedicellatus and S. cyperinus.

Marion County, Ohio. July 28, 2010

The bulrush genus Scirpus

consists of tall, tufted sedges with many small cone-like spikelets

arranged in a terminal cyme. They look fluffy! There are 8 species in

Ohio, all native. While they all have bristles surrounding their

achenes, two of them have especially long bristles, so they look

especially fluffy!! These are wool-grass, Scirpus cyperinus, and stalked

bulrush, S. pedicellatus.

Here they are together, slightly "posed." (The S. cyperinus on the left was plucked and carried over to be held next to the S. pedicellatus.)

Somewhat similar sedges at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. July 28, 2010.

Left: Scirpus cyperinus. Right: S. pedicellatus.

Here they are together, slightly "posed." (The S. cyperinus on the left was plucked and carried over to be held next to the S. pedicellatus.)

Somewhat similar sedges at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. July 28, 2010.

Left: Scirpus cyperinus. Right: S. pedicellatus.

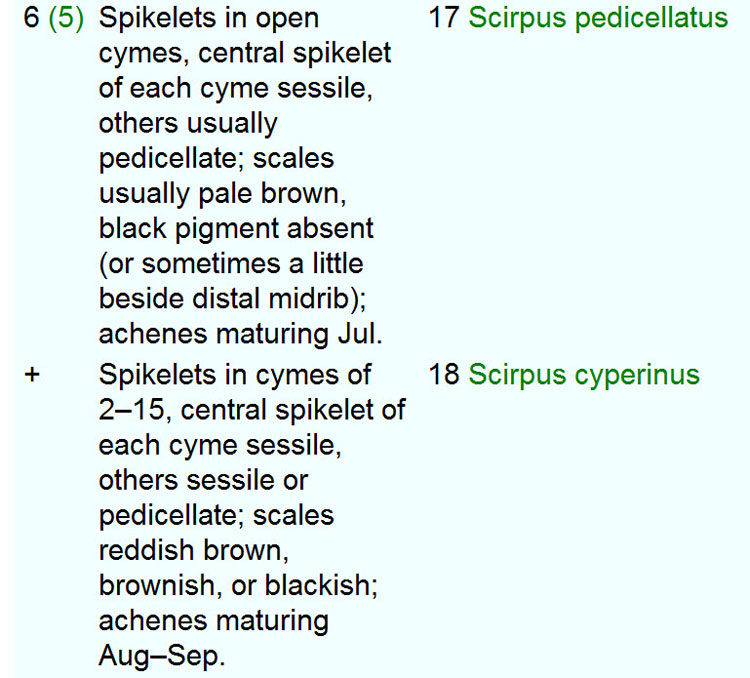

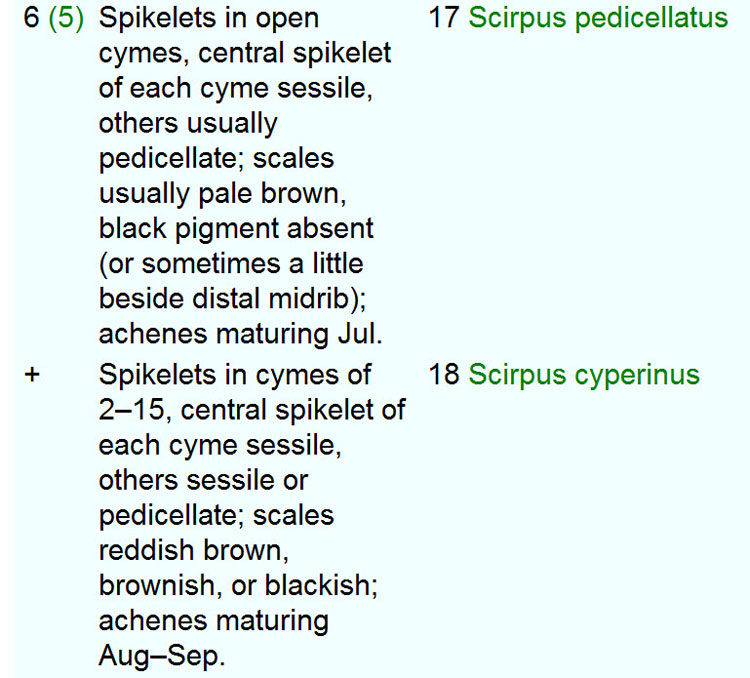

The more exciting find

is the

stalked bulrush, S.

pedicillatus. Apparently it is a county record! Wool-grass, S. cyperinus, is much more widely

distributed. As seen below on the couplet distinguishing them in the Flora

of North America,

stalked bulrush is characterized by having generally stalked, rather

than sessile, spikelets, and more early-maturing achenes.

Distinguishing traits of somewhat similar sedges.

(Flora of North America)

Distinguishing traits of somewhat similar sedges.

(Flora of North America)

Here's what stalked

bulrush

looked like at the beginning of the month.

Stalked bulrush at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. July 5, 2010.

...and here are its stalked spikelets, wooly, with mature achenes already!

Stalked bulrush at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. July 5, 2010.

Stalked bulrush at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. July 5, 2010.

...and here are its stalked spikelets, wooly, with mature achenes already!

Stalked bulrush at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. July 5, 2010.

...and here, for

comparison,

is a portrait of wool-grass. Note the more compact appearance owing to

the sessile spikelets.

Wool-grass at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. July 28, 2010.

Wool-grass at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. July 28, 2010.

Speaking of sedges with

the

word "rush" in their name, there's another one evident here today, a

type of "spike-rush," in the genus Eleocharis. Spike-rushes

are low-growing unbranched annual or perennial plants with a single

terminal spikelet. We have 19 spike-rushes in Ohio. This one, our most

common species, is an annual called "blunt spike-rush, Eleoocharis obtusa.

Blunt spike-rush at Killdeer Plains. July 28, 2010.

Blunt spike-rush at Killdeer Plains. July 28, 2010.

The name "Eleocharis" is from the Greek helos, a marsh, and charis, to grace. They do indeed

grace the marsh! Here's a closer view of the blunt spike-rush spikelet.

Blunt spike-rush spikelet.

Note achene surrounded by bristles.

Blunt spike-rush spikelet.

Note achene surrounded by bristles.

A

distinguishing feature of blunt spike-rush is the expanded style-base

atop each achene, forming a definite tubercle, visible in the photo

below (cropped and expanded from the photo above).

Blunt spike-rush achene. Note broadly triangular tubercle (expanded style-base) atop achene.

Blunt spike-rush achene. Note broadly triangular tubercle (expanded style-base) atop achene.

I Love Loosestrife

Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area

July 28, 2010

This isn't the evil

invasive

purple

loosetrife. It's lovely winged loosestrife, Lythrum alatum

(Lythraceae), a delicate native plant occasionally seen in

wet prairies, marshes, fens, and along shores of ponds.

Winged loosestrife is a summer-flowering wetland perennial.

July 28, 2010. Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area.

Winged loosetrife flowers typically have 6 petals

(unusual

for a non-monocot!) and six stamens. Winged loosetrife illustrates an unusual flower

variability called "heterostyly" that is found in only a few

species.

The flowers come in two different types distinguished by the length of the style (the upper portion of the female part of the flower, i.e., the pistil).

The long-styled "pin" flowers have six short stamens, located within the throat of the flower.

"Pin" flowers have a long style, and short stamens.

July 28, 2010. Killder Plains Wildlife Area.

An individual plant bears only one type of flower,

and

pollen from one type of flower is unable

to fertilize flowers of the same type as its own. Thus the plants are

not merely self-incompatable, but they are incompatable with half of

the plants in the population!

The particular type of heterostyly exhibited by winged loosetrife, wherein there are two style morphs, is "distyly." Other members of the genus, including the evil purple loosetrife, Lythrum salicaria, have an even more intricate "tristylous" heterostyly. This was of great interest to an obscure 19th century biologist named Charles Darwin.

In short, nature has ordained a most complex marriage-arrangement,

namely a triple-union between three hermaphtodites.

Winged loosestrife is a summer-flowering wetland perennial.

July 28, 2010. Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area.

The flowers come in two different types distinguished by the length of the style (the upper portion of the female part of the flower, i.e., the pistil).

The long-styled "pin" flowers have six short stamens, located within the throat of the flower.

"Pin" flowers have a long style, and short stamens.

July 28, 2010. Killder Plains Wildlife Area.

...while short-styled

"thrum" flowers have long-exert stamens.

"Thrum" flowers have a short style and long stamens.

July 28, 2010. Killder Plains Wildlife Area.

"Thrum" flowers have a short style and long stamens.

July 28, 2010. Killder Plains Wildlife Area.

The particular type of heterostyly exhibited by winged loosetrife, wherein there are two style morphs, is "distyly." Other members of the genus, including the evil purple loosetrife, Lythrum salicaria, have an even more intricate "tristylous" heterostyly. This was of great interest to an obscure 19th century biologist named Charles Darwin.

In short, nature has ordained a most complex marriage-arrangement,

namely a triple-union between three hermaphtodites.

A few years ago I saw

some

evil purple loosestrife plants growing at Killdeer.

Evil purple loosestrife at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area.

Wyandot County, Ohio. August 3, 2004.

Evil purple loosestrife at Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area.

Wyandot County, Ohio. August 3, 2004.

Here's a long-styled

evil

purple loosestrife flower, with a set of mid-length stamens and a set

of short ones.

Evil purple loosestrife, long-style flower. August 4, 2004.

Evil purple loosestrife, long-style flower. August 4, 2004.

Here's a mid-style evil

purple loosestrife, with one set of stamens above the stigma, and one

below it.

Evil purple loosestrife. mid-style flower. August 3, 204.

Evil purple loosestrife. mid-style flower. August 3, 204.

Here's hort-styles evil

purple loosestrife, with two sets of stamens at different positions

above the style.

Evil purple loosestrife, short-styled flower. August 3, 2004.

Evil purple loosestrife, short-styled flower. August 3, 2004.

Darwin

surmised that the different style-length morphs are an adaptation that

enhances reproductive success because they position a flower's style

corresponding to the

stamens of flowers of the other style mortps, i.e., the only ones that

can provide legitimate pollen. Under this model, the positioning is

critical because it effects a distribution of accumulated pollen on the

bodies of foraging insects complementary to the respective male and

female organs on compatible plants, thus promoting effective

cross-morph pollination. Modern research carefully looking at the

efficiency of legitimate pollen transfer in heterostylous plants has in

some instances found, and in others failed to find, support for

Darwin's hypothesis.

Bringing Neighbors Headaches

(Our Slighly Less Boring Backyard)

Summer, 2010

The 2010 Ohio Botanical

Symposium, held in late March, was awesome and

fun and informative. We marvelled at the best botanical finds of 2009,

gasped in horror at the status of the hemlock wooly adelgid, found

out why there are so many sedges in Ohio (and elsewhere), explored

the secrets of pollination, and followed in the footsteps of E. Lucy

Braun though the restoration of Agave Ridge Prairie.

Among the highest of the highlights of the Symposium was the keynote speech, "Bringing Nature Home," by University of Delaware Professor Douglas W. Tallamy, author of a book by that name, subtitled "How You Can Sustain Wildlife With Native Plants." This address was a transformative experience for many in the audience, and, more to the point, for their suburban lawns.

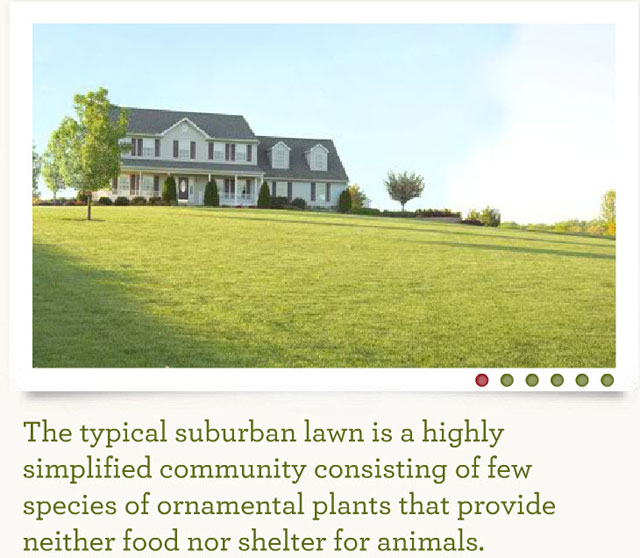

Dr. Tallamy, an entomologist, explained that wildlife diversity in North America could be enhanced tremendously if the vast acreage covered by suburban lawns and gardens were more productive of insects. Here's how he so aptly puts it on his informative web site http://www.plantanative.com/

Commentary on the lawn on Douglas Tallamy's web site.

(CLICK IMAGE FOR INFO)

...and it could be incredibly annoying to our neighbors to have a big "weed patch," so let's do it!

Here's a shot taken from an upstairs window looking down on a very boring backyard just a few weeks after the Symposium. If you look closely, you might be able to make out some thin stakes set a few feet apart. These stakes mark the boundary of of our future BNH Garden!

Boring Backyard Before BNH. April 10, 2010.

Among the highest of the highlights of the Symposium was the keynote speech, "Bringing Nature Home," by University of Delaware Professor Douglas W. Tallamy, author of a book by that name, subtitled "How You Can Sustain Wildlife With Native Plants." This address was a transformative experience for many in the audience, and, more to the point, for their suburban lawns.

Dr. Tallamy, an entomologist, explained that wildlife diversity in North America could be enhanced tremendously if the vast acreage covered by suburban lawns and gardens were more productive of insects. Here's how he so aptly puts it on his informative web site http://www.plantanative.com/

Commentary on the lawn on Douglas Tallamy's web site.

(CLICK IMAGE FOR INFO)

His reasoning is that

insects, which he aptly calls

"bird food," are adapted to eat native, not exotic, plant species.

Shunned by bugs, the primarily Asian and European plants favored by

nurseries and their gardening customers do not adequately fulfill the

important role at the base of the food chain. Lawns, he explained,

are

about as good (bad) as roads and parking lots in terms of their ability

to

nurture and

sustain wildlife. By planting natives in our gardens and landscaped

lawns, and by converting chunks of lawn to mixed native plantings, we

could go a long ways toward giving wildlife a helping hand.

...and it could be incredibly annoying to our neighbors to have a big "weed patch," so let's do it!

Here's a shot taken from an upstairs window looking down on a very boring backyard just a few weeks after the Symposium. If you look closely, you might be able to make out some thin stakes set a few feet apart. These stakes mark the boundary of of our future BNH Garden!

Boring Backyard Before BNH. April 10, 2010.

Here's the BNH garden

after

the roto-tilling, and the initial planting, were performed. The

bushier plants along the back and the forward edges on the right are

some "legacy" plants that have sentimental value and/or are natives

that belong in the new scheme. Pursuant to Dr. Tallamy's

recommendations, we "tamed" the area by keeping a mowed path

through it that also serves as a great observation area.

Early stages of BNH garden. May 28, 2010.

Some of our BNH garden plants came from Scioto Gardens, a nursery in Delaware, Ohio that specializes in native plants. The trip to the nursey was especially fun, because in addition to plants we got an engaging garden mascot -- a dinosaur scultpure made of old farm hand tools. His name is "Erasmus," and he's (barely) visible in the photo above.

Here's a zoom-crop of the Erasmus on sentry duty.

Erasmus settles in to the BNH garden. May 28, 2010.

Early stages of BNH garden. May 28, 2010.

Some of our BNH garden plants came from Scioto Gardens, a nursery in Delaware, Ohio that specializes in native plants. The trip to the nursey was especially fun, because in addition to plants we got an engaging garden mascot -- a dinosaur scultpure made of old farm hand tools. His name is "Erasmus," and he's (barely) visible in the photo above.

Here's a zoom-crop of the Erasmus on sentry duty.

Erasmus settles in to the BNH garden. May 28, 2010.

The other source of BNH

plants was the OSU-Marion Prairie Nature Center plant sale. Here are

some of the plants we "bought" there. (If I ever give them the

money I "promised," to pay, I'll remove the quotation marks around

"bought.")

MOUSEOVER the IMAGE for

PLANT ID

Prairie plants for the BNH garden.

Prairie plants for the BNH garden.

We tried to plant as

many

species as possible, including forbs and graminoids. (A

"forb" is an herbaceous

plants that isn't a graminoid, i.e., what is normally called a

"wildflower.")

By mid-summer, the BNH

garden

started looking like an ecosystem, or what some people might call a

"weed patch." Mission accomplished!

BNH garden during mid-summer. July 25, 2010.

...and Erasmus is fitting in quite well!

Erasmus is quite comfortable in his role as garden guarder. Summer, 2010.

BNH garden during mid-summer. July 25, 2010.

...and Erasmus is fitting in quite well!

Erasmus is quite comfortable in his role as garden guarder. Summer, 2010.

The following is a

sample of

snapshots taken in and near the BNH garden this summer.

One of the plants we got at Scioto Gardens is a Helianthus (sunflower) in the "native to North America but not Ohio" category, and it seems to be a big hit with the bugs. Here's a clouded sulfur butterfly, Colias philodice, nectaring on it, the view of which is partly blocked by an incoming bumblebee.

Sunflower with clouded sulfur butterfly and incoming bumblebee.

One of the plants we got at Scioto Gardens is a Helianthus (sunflower) in the "native to North America but not Ohio" category, and it seems to be a big hit with the bugs. Here's a clouded sulfur butterfly, Colias philodice, nectaring on it, the view of which is partly blocked by an incoming bumblebee.

Sunflower with clouded sulfur butterfly and incoming bumblebee.

An

interesting thing about

this sunflower is that it seems to be an exceptional nectar

source for night-foraging moths. Here's one that, insasmuch as it looks

like a little airplane, can be told is is a type of "plume moth," i.e.,

a member of the family Pterophoridae, consisting of approx. 140 species

that are essentially impossible to tell apart in the field.

Plume moth on sunflower at night.

Plume moth on sunflower at night.

...and apparently

bumblebees

sleep there, just hanging on. Who knew?

Bumblebee asleep at the sunflower.

Bumblebee asleep at the sunflower.

An striking

early-flowering

prairie wildflower is Ohio spiderwort, Tradescantia ohioesis

(Commelinaceae).

Ohio spiderwort produces many-flowered umbels.

Within each umbel, only a few flowers are in bloom on a given day.

Ohio spiderwort produces many-flowered umbels.

Within each umbel, only a few flowers are in bloom on a given day.

Here's a little video of

a

bumblee enjoying the spiderwort.

Contributing to the effectiveness of Dr. Tallamy's message is the fact that it is data-driven. He and his research associates compiled a list of North American woody plants ranked by degree to which they are food for numbers of lepidopterans (moths and butterflies). "Leps" were chosen because they are especially well studied and also are generally very good "bird food." Topping the list are oaks (genus Quercus, family Fagaceae), with 534 species supported. So we bought a little Shumard oak (Quercus shumardii) sapling.

Oaks, like this Shumard oak, support a great number of insects.

Little video of a

bumblebee

enjoying the spiderwort.

Another big thrill of

having

a BNH garden is to have something in common with Ohio Governor Ted

Strickland: We both have Siphium in our backyard!

A tale of two

backyards.

Left: Governor's

mansion,

with prairie-dock (Silphium terebinthinaceum).

Right: Bob's mansion,

with

compass-plant (S. laciniatum).

Contributing to the effectiveness of Dr. Tallamy's message is the fact that it is data-driven. He and his research associates compiled a list of North American woody plants ranked by degree to which they are food for numbers of lepidopterans (moths and butterflies). "Leps" were chosen because they are especially well studied and also are generally very good "bird food." Topping the list are oaks (genus Quercus, family Fagaceae), with 534 species supported. So we bought a little Shumard oak (Quercus shumardii) sapling.

Oaks, like this Shumard oak, support a great number of insects.

I think it was just

"chillin'" here rather than having been raised upon the oak, but it's

nice to see this happy short-horned grasshopper (Order

Orthoptera) in our BNH garden .

Short-horned grasshopper on oak twig.

Short-horned grasshopper on oak twig.

Happily, several of our

herbaceous plants (inccluding Helianthus)

rank high on Dr.

Tallamy's list of herbaceous "best bets." Among them is

a grass called little bluestem, Schizachyrium

scoparium

(Poaceae). This prairie plant that can sometimes be identified, even

when non-flowering, by its flattened culms and ligules that are a zone

of hairs.

Little bluestem and short-horned grasshopper.

Little bluestem and short-horned grasshopper.

We

planted a couple other native praire grasses that might have to be kept

in check as sometimes they can be a little bit too successful in

prairie planting, crowding out the forbs.

Two tallgrass praire tall grasses at the BNH garden.

Left: Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans). Right: Big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii).

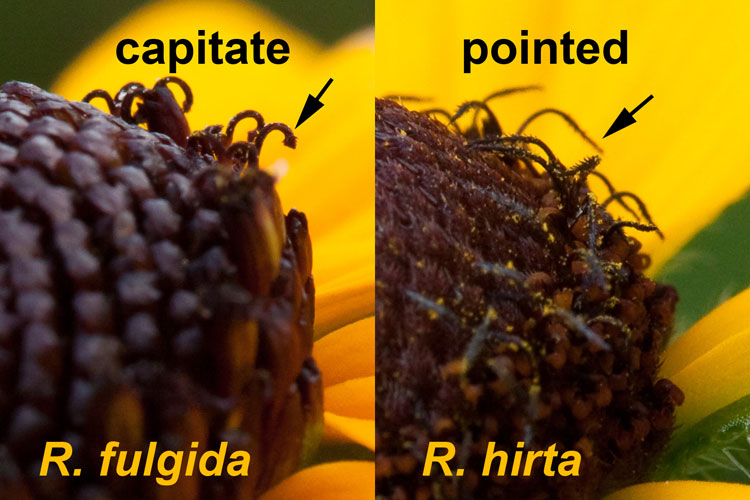

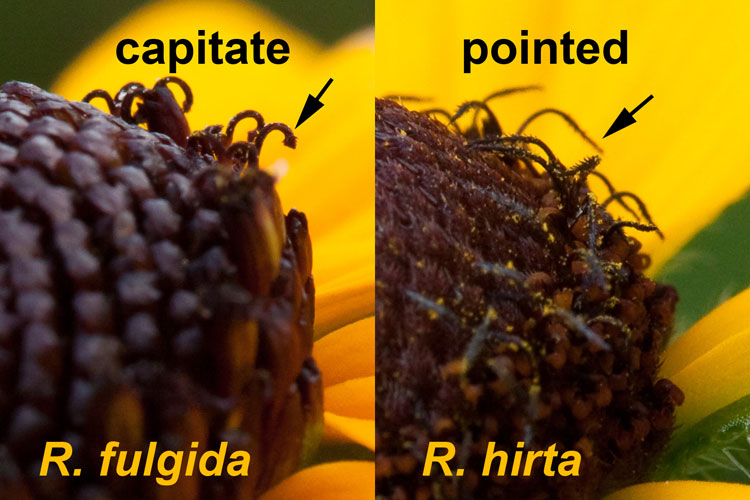

Various members of the genus Rudbeckia in the Asteraceae are highly regarded by Team Tallamy for their association with insects. Two of them, black-eyed Susan (R. hirta) and orange coneflower (R. fulgida), are low-growing, short-lived perennials that quite resemble one another.

This is black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta):

Black-eyed Susan is an easy-to-grow prairie forb that often flowers in its first year.

Two tallgrass praire tall grasses at the BNH garden.

Left: Indian grass (Sorghastrum nutans). Right: Big bluestem (Andropogon gerardii).

Various members of the genus Rudbeckia in the Asteraceae are highly regarded by Team Tallamy for their association with insects. Two of them, black-eyed Susan (R. hirta) and orange coneflower (R. fulgida), are low-growing, short-lived perennials that quite resemble one another.

This is black-eyed Susan (Rudbeckia hirta):

Black-eyed Susan is an easy-to-grow prairie forb that often flowers in its first year.

This is orange

coneflower (Rudbeckia fulgida).

Orange coneflower: less common, and more of a prairie specialist, than black-eyed Susan.

These two Rudbeckia species can be a challenge to distinguish because some of their diagnostic traits, such as hairiness and flower color, seem more a matter of degree than of kind. A close look at the flower heads, however, shows a great field mark. The style-branches of orange coneflower end in a fist-shaped tip, whereas those of black-eyed Susan slenderly taper to a point.

Style-branches of two similar Rudbeckia species at the BNH garden.

Orange coneflower: less common, and more of a prairie specialist, than black-eyed Susan.

These two Rudbeckia species can be a challenge to distinguish because some of their diagnostic traits, such as hairiness and flower color, seem more a matter of degree than of kind. A close look at the flower heads, however, shows a great field mark. The style-branches of orange coneflower end in a fist-shaped tip, whereas those of black-eyed Susan slenderly taper to a point.

Style-branches of two similar Rudbeckia species at the BNH garden.

There are legumes

(family

Fabaceae) in the BNH garden. One of them is an annual which I hope is

capable of self-pollination because there's only one plant. This is

butterfly-pea, Chamaecrista

fasciculata.

Butterfly-pea is a an annual plant.

Butterfly-pea is a an annual plant.

Butterfly-pea, like many

legumes, engages in an interesting mutualism with ants. The plant

produces food for the insects on special glands at the base of the

leaves, called "extrafloral nectaries." In return the ants defend the

plants against herbivores.

Ant feeds on butterfly-pea extrafloral nectary at BNH garden.

Ant feeds on butterfly-pea extrafloral nectary at BNH garden.

A close relative of

butterfly-pea is wild senna, Senna

hebecarpa. Senna is a perennial, and much taller than Chamaecrista.

Wild senna is a tall perennial legume.

Wild senna is a tall perennial legume.

Senna,

like Chamaecrista, attracts

ants to

extrafloral nectaries at the base of its leaves.

Ant associate of senna at the BNH garden.

Ant associate of senna at the BNH garden.

Milkweeds, in addition

to

being the most wonderful things that nature ever selected, and way

better than orchids (which really isn't saying very much), are known

for their special insect

associations.

Here's a beetle larva feeding on a common milkweed leaf. Famously, there aren't many things that do this, so it wasn't too hard to pinpoint this as a milkweed leaf beetle, Labidomera clivicollis (Chrysomelidae), the adults of which (surprise) are red and black, and quite beautiful. I'm afraid this individual may have fulfilled its destiny as "bird food," but we'll look for them next year.

Something that isn't a monarch merrily munches milkweed at the BNH garden.

It was a treat this summer to see both types of milkweed bug on milkweeds at the BNH garden. Milkweed bugs feed on milkweed seeds, often before the fruits open to release them. They accomplish this by inserting their proboscis through the ovary and then into a seed, dissolving its contents with injected saliva, and then sucking up the juicy seed-smoothie.

Swamp milkweed fruit at BNH garden, with large milkweed bug (Oncopeltus fasciatus) nymphs.

Here's a beetle larva feeding on a common milkweed leaf. Famously, there aren't many things that do this, so it wasn't too hard to pinpoint this as a milkweed leaf beetle, Labidomera clivicollis (Chrysomelidae), the adults of which (surprise) are red and black, and quite beautiful. I'm afraid this individual may have fulfilled its destiny as "bird food," but we'll look for them next year.

Something that isn't a monarch merrily munches milkweed at the BNH garden.

It was a treat this summer to see both types of milkweed bug on milkweeds at the BNH garden. Milkweed bugs feed on milkweed seeds, often before the fruits open to release them. They accomplish this by inserting their proboscis through the ovary and then into a seed, dissolving its contents with injected saliva, and then sucking up the juicy seed-smoothie.

Swamp milkweed fruit at BNH garden, with large milkweed bug (Oncopeltus fasciatus) nymphs.

The

excellent 2nd half of Bringing

Nature Home, entitles "What Does Bird Food Look Like?" is

essentially a primer

of entomology. Here, in the

section on Hemiptera (true bugs), Tallamy relates an amazing thing

about the large milkweed bug. He tells us "The observant gardener will

notice that the large milkweed bug does not appear until later in the

summer month, and that when it first shows up, it is always an adult.

Where has it been hiding out?" He explains that, in the 1960's,

ecologist Hugh Dingle discovered that Oncopeltus

is a migrating insect that spends the winter along the Gulf Coast,

where milkweed seeds are available year-round. The timing of its

northward migration coincides with the appearance of milkweed fruits as

they become mature farther and farther north. The bugs follow the

supply of

their food source, fresh milkweeed seeds.

Oncopeltus is distinguished by its large size, and the large black band running across its wings.

Small mikweed bug at BNH garden.

Oncopeltus is distinguished by its large size, and the large black band running across its wings.

The small milkweed bug, Lygaeus kalmii,

has more of an hour-glass shape on its wings, flanked by black spots

that are not continuous

across the wings.

Small mikweed bug at BNH garden.

A common milkweed plant

at

night is a hiding place for a crab spider.

Crab spider Misumena vatia at rest beneath common milkweed leaf in BNH garden.

Crab spider Misumena vatia at rest beneath common milkweed leaf in BNH garden.

There

are members of the

parsely (carrot, celery, umbel, whatever) family, Apiaceae, in the BNH

garden, one of which is this scary-looking rattlesnake-master, Eryngium yuccifolium.

Rattlesnake-master produces many small flowers in a globose head --not a typical umbel!

Rattlesnake-master produces many small flowers in a globose head --not a typical umbel!

...and seen here in

fruit, a

spring-flowering prairie forb called "golden Alexanders," (Zizia aurea). This

genus is a lot like Thaspium (meadow-parsnip), except that Thaspium

fruits are much more prominently winged that are those of Zizia.

Golden Alexanders in fruit. Each one will eventually split into 2 one-seeded units.

Golden Alexanders in fruit. Each one will eventually split into 2 one-seeded units.

A few insects seen in

the

yard, although not on the BNH plants, were nonetheless an inspiration

to promote their kind by planing more natives. Here's a narrow-winged

tree-cricket, Oecanthus niveus.

Narrow-winged tree cricket on an apple tree near the BNH garden.

Narrow-winged tree cricket on an apple tree near the BNH garden.

Until

this moment I was

unaware that there is a matid native to Ohio. This beauty, seen on

a magnolia shrub, is the Carolina mantid, Stagmomantis carolina. Smaller

than the introduced Chinese mantid (Tenodera

aridifolia) and European mantid (Mantis religiosa),

they are nonetheless formidable insect predators. Like their alien

brethren, they overwinter as eggs deposited in a frothy mass., and it

take the entire summer for to reach sexual maturity. This is, I

believe, a female. I hope she found a mate!

Carolina mantid near the BNH garden.

Carolina mantid near the BNH garden.