(Additional content at flickr Photostream and YouTube Channel)

If you have botany questions or comments please email BobK . Thanks!

July 20, 2010

Catawba Island, Portage County, Ohio.

Today we drove to the

tip of Catawba island and waved bye-bye to the kid, who

caught Miller's Ferry to South

Bass Island from which she hopped over to OSU's F.T. Stone Laboratory

on wee little Gibraltar Island for five weeks of study during

which she changed from someone who knew way less about entomology than

me into someone who knows way more about entomology than me.

Because

that happened by her learning a lot about bugs instead of me

forgetting a lot about them (although I think that may have happened also), it's

great! Stone Lab is great! Go there and learn about bugs!

On the way back, her happy mom and I drove over the narrow inlet that almost makes Catawba Island an island, an inlet that is home to a huge and striking population of a huge and striking plant, Nelumbo lutea (Nelumbonaceae, the lotus family). Nelumbo, while it is a huge plant, is not a huge genus. There are just two species, constituting one of the many intriguing eastern Asian - eastern North American pairs of closely related but widely disjunct taxa. This peculiar distribution pattern is generally attributed to the fragmentation of a once-contiguous mixed mesophytic forest, the so-called "arcto-tertiary geoflora." This biome spread across the northern hemisphere during a warm period from 65 to 15 million years ago, when the continents were joined by the Bering land bridge. The Asian lotus species, Nelumbo nucifera, is an important spiritual symbol in many eastern religions, hence one prevalent common name for it is "sacred lotus." Because we have a different cultural tradition, based upon the separation of church and stamen, perhaps our species should be called "secular lotus." Perhaps, but it's usually just called "American lotus."

Secular (American) lotus at Catwaba Island inlet, Portage County, Ohio. July 20, 2010.

On the way back, her happy mom and I drove over the narrow inlet that almost makes Catawba Island an island, an inlet that is home to a huge and striking population of a huge and striking plant, Nelumbo lutea (Nelumbonaceae, the lotus family). Nelumbo, while it is a huge plant, is not a huge genus. There are just two species, constituting one of the many intriguing eastern Asian - eastern North American pairs of closely related but widely disjunct taxa. This peculiar distribution pattern is generally attributed to the fragmentation of a once-contiguous mixed mesophytic forest, the so-called "arcto-tertiary geoflora." This biome spread across the northern hemisphere during a warm period from 65 to 15 million years ago, when the continents were joined by the Bering land bridge. The Asian lotus species, Nelumbo nucifera, is an important spiritual symbol in many eastern religions, hence one prevalent common name for it is "sacred lotus." Because we have a different cultural tradition, based upon the separation of church and stamen, perhaps our species should be called "secular lotus." Perhaps, but it's usually just called "American lotus."

Secular (American) lotus at Catwaba Island inlet, Portage County, Ohio. July 20, 2010.

The lotus family, Nelumbonaceae, consists only of the genus Nelumbo. These are perennial

herbs with stout fleshy rhizomes, bearing disk-shaped leaves held above

the water by a petiole (leafstalk) that is attached in the center of

the leaf, an attachment type that is called "peltate."

Secular (American) lotus. Note peltate leaves held above the water.

Secular (American) lotus. Note peltate leaves held above the water.

The flowers are bisexual (hermaphroditic, i.e., containing both stamens and carpels), radially symmetric, large and showy.

They are held stiffly upwards, just overtopping the leaves. The

perianth consists of 2-5 outermost sepals, grading into 20-30 spirally

arranged petals that are yellow in our species, pink to red in the Asian N. nucifera.

Secular (American) lotus. Note numerous, spirally arranged petals and stamens.

Secular (American) lotus. Note numerous, spirally arranged petals and stamens.

Each

flower bears numerous widely separated ovaries loosely embedded in

pockets just beneath the flat top of an unique enlarged inverted

cone-shaped receptacle that

eventually develops into Large Lotus Pods that are perfect for adding

texture and a touch of rustic charm to your floral arrangements.

Nelumbo receptacle shortly after petal-fall, but before the development of rustic charm.

Nelumbo receptacle shortly after petal-fall, but before the development of rustic charm.

There are no styles; the

stigma just sits atop the ovary, making the following zoomed-in piece

of the picture above look really creepy, like a slew of alien pop-eyes

all looking sort of, but not quite, at the same thing.

Spooky zoomed-in view of Nelumbo receptacle, showing ovaries with sessile stigmas.

Numerous single-seeded fruits sunken into pits atop an enlarged receptacle constitute a peculiar type of "false fruit" that is sometimes called an "accessory fruit." The only other vaguely similar accessory fruits are the wholly unrelated strawberry-type ones in the rosaceous genera Fragaria and Duchesnia. And yes, these lotus infructescences are those charming things you sometimes see in hobby shopes, for use in flower arrangements.

Spooky zoomed-in view of Nelumbo receptacle, showing ovaries with sessile stigmas.

Numerous single-seeded fruits sunken into pits atop an enlarged receptacle constitute a peculiar type of "false fruit" that is sometimes called an "accessory fruit." The only other vaguely similar accessory fruits are the wholly unrelated strawberry-type ones in the rosaceous genera Fragaria and Duchesnia. And yes, these lotus infructescences are those charming things you sometimes see in hobby shopes, for use in flower arrangements.

Arghh. Crass commercialism --the downside of "secular"?

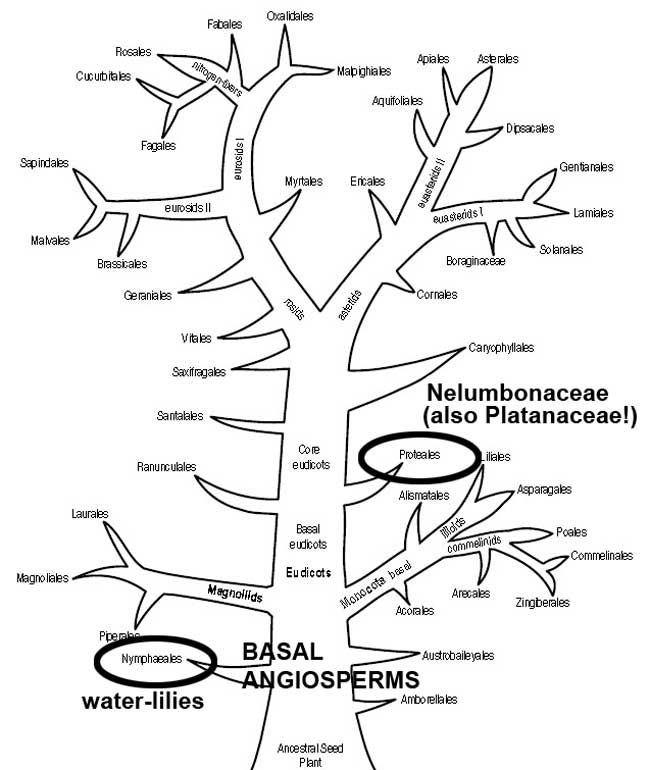

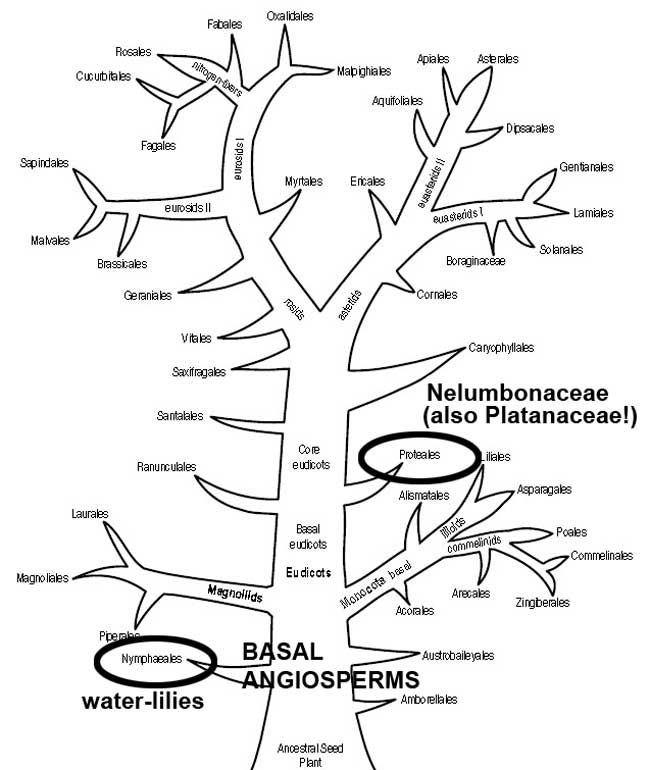

The taxonomic position of Nelumbo has recently been revised. Traditionally, owing to a strong resemblance to the "water-lilies" Nymphaea and Nuphar which are also

robust aquatic herbs with circular leaves and showy flowers composed of

many separate parts spirally arranged, they were placed along with the

water-lilies either in the same family (Nymphaeaceae) or alongside them

in a separate family, both within the Order Nymphaeales.

During the past few decades there's been a revolution, still ongoing, in plant classification fostered both by a greater acceptance of cladistic systems that are very strict about basing classification on phylogeny, and the wealth of data from DNA sequences. One very good guide to the new view of flowering plant systemetics is a great book called "A Tour of the Flowering Plants" by Priscilla Spears, published in 2006 by the Missouri Botanical Garden Press.

The book is based on the classification system of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. It includes a simplified tree that Spears calls a "map to help you find your way around the thowering plants." The "map," and accompanying text, explains that there is a small group comprising only about 3% of the flowering plants that diverged early from the flowering plant lineage, appropriately termed "basal angiosperms." Close to the ancestral seed plants, this group includes the water lilies (Nymphaeales), but not the lotuses. The Nelumbonaceae is in the Proteales, located farther up the tree in the "Basal Eudicots."

BUY THIS BOOK!

During the past few decades there's been a revolution, still ongoing, in plant classification fostered both by a greater acceptance of cladistic systems that are very strict about basing classification on phylogeny, and the wealth of data from DNA sequences. One very good guide to the new view of flowering plant systemetics is a great book called "A Tour of the Flowering Plants" by Priscilla Spears, published in 2006 by the Missouri Botanical Garden Press.

BUY THIS BOOK!

The book is based on the classification system of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group. It includes a simplified tree that Spears calls a "map to help you find your way around the thowering plants." The "map," and accompanying text, explains that there is a small group comprising only about 3% of the flowering plants that diverged early from the flowering plant lineage, appropriately termed "basal angiosperms." Close to the ancestral seed plants, this group includes the water lilies (Nymphaeales), but not the lotuses. The Nelumbonaceae is in the Proteales, located farther up the tree in the "Basal Eudicots."

BUY THIS BOOK!

Spears' treatment of the Nelumbonaceae includes the pleasant surprise that, in our flora, the closest relative of lotus is Platanus, our American sycamore! Look

how well it's explained that the similarities between the two families

of aquatic herbs is apparently due to convergent evolution. DNA data

led to this findking, which has since been corroborated by a closer

look at anatomical and developmental traits shared by Nelumbo and Platanus.

"Just So" Floral Extrafloral Nectaries on Sullivant's Milkweed?

July 19, 2010

Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, Marion County, Ohio

An interesting feature exhibited by a few plants is the "extrafloral nectary," a glandular structure, usually at the base of a leaf, that produces an energy-rich sugary substance fed upon by some insect that is not involved in pollination. Typically the plant-insect relationship is a mutualism, wherein the insects, most often ants, contribute to the plant's well-being by by acting as bodyguards, fending off potential herbivores. Ants feeding on narrow-leaved vetch extrafloral nectaries last year can be seen here.

However, could there be nectaries that are "extrafloral" in the sense that they serve to attract non-pollinating insects, but that are "floral" in that they are indeed located on the flowers? It seems that maybe there's something like that going on with Sullivant's milkweed.

Sullivant's Milkweed. June 19, 2010. Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area.

See below for closer look at framed region.

Examining

closely these

flowers under a dissecting scope, Team Millkweed discovered a

peculiarity that doesn't seem yet to have been reported in the fairly

exhaustive scientific literature on milkweed flower structure and

associated reproductive ecology. This is a set of 10 small,

upwardly-projecting swollen flaps of tissue located where the hood

rises off the central column. Each flap seems to loosely cover a small

opening to the nectar-containing portion of the flower, i.e., the

interior base of the hoods and the adjacent stigmatic chambers. Two of

these flaps are depicted in the photo below, an

enlargement of the boxed area of the photo above. Are they nectaries?

Possible floral extrafloral nectaries on Sullivant's milkweed.

Possible floral extrafloral nectaries on Sullivant's milkweed.

One of the tenets of

evolutionary theory is, of course, that a novel and intricate aspect of

an organism constitutes an adaptation, i.e., a genetically based

feature that increases its ability to survive and reproduce in a

particular environment. However, while the value of a particular trait

may sometimes seem apparent,

strong experimental evidence is often

lacking concerning the specific way (or ways) in which it benefits the

organism. Thoughtful

tentative explanations, intruguing but speculative, are often

criticized. Such untested claims have been called "Just So Stories"

in a derisive homage to Rudyard Kipling's set of childen's stories such

as "How the Camel Got His Hump," etc.

Here's a "Just So" story about milkweeds. Perhaps this little set of openings to the nectar at the base of the flower provides a means by which nectar feeding but non-pollinating insects such as various bugs, ants, flies, and very small moths and bees can do their useless nectar feeding in a manner that interferes less with the beneficial pollinating foragers.

Here's a large milkweed bug, Oncopeltus fasciatus, feeding directly from the hood in a manner that might discourage a honeybee or a butterfly (potential pollinators) from occupying that same space.

Large milkweed bug drinking nectar directly from the hood.

July 19, 2010. Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. Marion County, Ohio.

Here's a "Just So" story about milkweeds. Perhaps this little set of openings to the nectar at the base of the flower provides a means by which nectar feeding but non-pollinating insects such as various bugs, ants, flies, and very small moths and bees can do their useless nectar feeding in a manner that interferes less with the beneficial pollinating foragers.

Here's a large milkweed bug, Oncopeltus fasciatus, feeding directly from the hood in a manner that might discourage a honeybee or a butterfly (potential pollinators) from occupying that same space.

Large milkweed bug drinking nectar directly from the hood.

July 19, 2010. Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. Marion County, Ohio.

...and

here's an instance where the bug seems to have its beak on the

auxilliary structure that, if it is serving as a nectary, is doing so

in a manner that facilitates feeding from a lower position, freeing the

hood area for foraging by insects more likely to transfer pollinia.

Large milkweed bug drinking nectar from below.

July 19, 2010. Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. Marion County, Ohio.

Large milkweed bug drinking nectar from below.

July 19, 2010. Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. Marion County, Ohio.

Here's a similar set of

photos for an unidentified fly. First, plunk down in the hood.

Fly drinking nectar directly from the hood.

July 19, 2010. Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. Marion County, Ohio.

Fly drinking nectar directly from the hood.

July 19, 2010. Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. Marion County, Ohio.

...and

here it is again, possibly exploiting the putative "floral extrafloral

nectary," well out of the way of helpful honeybees.

Fly drinking nectar directly from below.

July 19, 2010. Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. Marion County, Ohio.

Fly drinking nectar directly from below.

July 19, 2010. Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area. Marion County, Ohio.

Milkweeds are People, Too!

July 19, 2010.

Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, Marion County, Ohio

One of the most enjoyable

arguments you can have with someone, and it really doesn't matter which

side you take, is whether or not individual non-human animals are

distinctive like people are. The fact that

humans are instantly recognizable seems important because,

as social animals, we engage in reciprocal exchanges, altruism and

trade. Hence we need to keep track of who is trustworthy, owes us a

favor, or is a cheater. But what about all those animals that seem to

look exactly alike, like toads and birds? The fact that I

can't tell one from another might not mean much, because, not

being a toad or a bird, I don't have an eye for what makes each one of

them unique.

But there shouldn't be any debate about individual Sullivant's milkweeds. I have no idea why, but they're wildly variable and distinctive! Team Milkweed learned this during field work examining the potential for variation in gene flow among plants that consisted either of large multi-stemmed clones, or small few-stemmed ones. Based on appearance, we had to try to guess whether stems ("ramets") standing alongside one another belonged either to the same or to different genetic individuals ("genets").

To get a feeling for phenotypic variation in Sullivant's milkweed, I merrily pranced across the meadow, and snapped pictures of bundled-together pairs of adjacent stems that resembled each other in terms of flower colors, the shapes of their flowers, and the timing of flowering.

Two milkweed stems bundled together. July 19, 2010. Killdeer Plains.

Yellow-boxed area encloses flowers from both stems, featured in Gallery 2 below.

Here's Image Gallery 1, demonstrating among-plant variation in Sullivant's milkweed.

But there shouldn't be any debate about individual Sullivant's milkweeds. I have no idea why, but they're wildly variable and distinctive! Team Milkweed learned this during field work examining the potential for variation in gene flow among plants that consisted either of large multi-stemmed clones, or small few-stemmed ones. Based on appearance, we had to try to guess whether stems ("ramets") standing alongside one another belonged either to the same or to different genetic individuals ("genets").

To get a feeling for phenotypic variation in Sullivant's milkweed, I merrily pranced across the meadow, and snapped pictures of bundled-together pairs of adjacent stems that resembled each other in terms of flower colors, the shapes of their flowers, and the timing of flowering.

Two milkweed stems bundled together. July 19, 2010. Killdeer Plains.

Yellow-boxed area encloses flowers from both stems, featured in Gallery 2 below.

Here's Image Gallery 1, demonstrating among-plant variation in Sullivant's milkweed.

GALLERY

1: VARIATION

BETWEEN CLONES

(YELLOW BOXED AREAS ARE FEATURED IN SECOND GALLERY BELOW )

(YELLOW BOXED AREAS ARE FEATURED IN SECOND GALLERY BELOW )

Image Gallery 2 zooms in on the flowers, highlighting within-clone similarity. Like the gallery above, it's also a good example of that annoying optical illusion where you see little gray squares that aren't really there.

GALLERY

2: SIMILARITY

WITHIN CLONES

(YELLOW-BOXED AREAS FROM FIRST GALLERY)

(YELLOW-BOXED AREAS FROM FIRST GALLERY)

Many Milkweed Metazoans

Early-Mid July, 2010

Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, Marion County, Ohio

It's plainly evident that the

European honeybee, Apis mellifera,

is

the principal, indeed essentially the only, pollinator of Sullivant's

milkweed here at Killdeer Plains. The bees are abundant, they forage

extensively, and can regularly be seen carrying milkweed pollinaria.

Here's yet another snapshot of a milkweed umbel featuring

a foraging bee.

MOUSEOVER the image to see more closely the pollinaria attached to her

legs.

Honeybees forage avidly on Sullivant's killweed at Milkdeer. July 19, 2010.

...and they doubtlessly transfer pollinia from plant to plant as they travel.

Honeybee carries pollinia at Killdeer Plains. July 19, 2010.

Honeybee beset with pollinaria somehow manages not to insert any, or withdraw more.

MOUSEOVER the IMAGE for

ZOOM-CROP of BEE

Honeybees forage avidly on Sullivant's killweed at Milkdeer. July 19, 2010.

...and they doubtlessly transfer pollinia from plant to plant as they travel.

MOUSEOVER the IMAGE to see

ZOOM-CROP of BEE

Honeybee carries pollinia at Killdeer Plains. July 19, 2010.

Here's yet another video of a

honeybee foraging on Sullivant's milkweed. I've got dozens of these and

have watched them all, closely, in a vain (fruitless vain, not

egotistical vain, but maybe some of that too because they are quite

nice videos)

attempt to catch one in the act of pollinarium withdrawl or pollinium

insertion. So far, no luck. Maybe milkweeds like their privacy.

Honeybee beset with pollinaria somehow manages not to insert any, or withdraw more.

Descriptions of milkweed

pollination sometimes include a scenario wherein a foraging insect will

get its foot caught in the stigmatic groove and, while trying to

extricate itself, withdraw a pollinarium and then fly off with it.

That may be happen, but it seems the pollinaria can be withdrawn

cleanly,

without all that drama. Nonetheless, bees often do get caught, and stay

that way. Here's a honeybee with several feet

snared.

Honeybee fast on milkweed. July 10, 2010.

Honeybee fast on milkweed. July 10, 2010.

Here's

the video they

show in at scary special assembly every year at Honeybee High, to

frighten those crazy kids, and keep them from playing on the milkweeds.

But they

never listen.

Honeybee snagged by milkweed flower. Sad, so sad.

Honeybee snagged by milkweed flower. Sad, so sad.

But its not all honeybees all the

time. Other insects visit the flowers, although they don't seem to

carry many (any) pollinia. A terrific milkweed associate is the large

milkweed bug, Oncopeltus fasciatus.

This is a type of

"seed bug" that does, indeed, feed largely on milkweed seeds. They are

often accessed by piercing the wall of a milkweed fruit. But they also

sip nectar, passing time until fruits arrive.

Large milkweed bug sips nectar. Killdeer Plains. July 19, 2010.

Large milkweed bug is a star! (This is very "meta.")

Large milkweed bug sips nectar. Killdeer Plains. July 19, 2010.

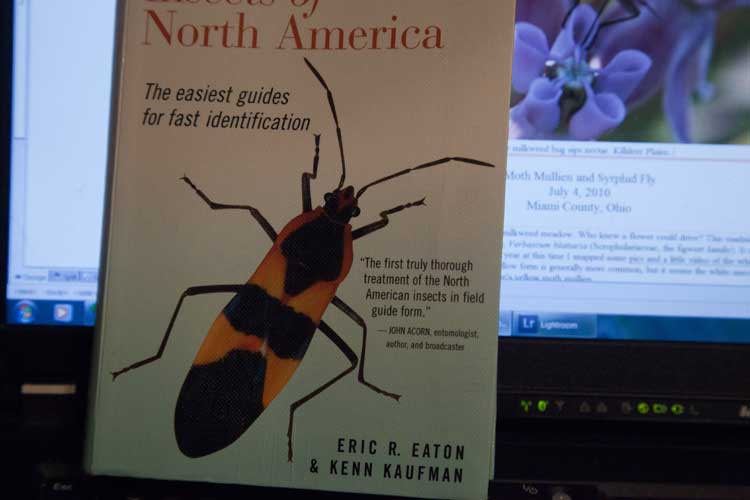

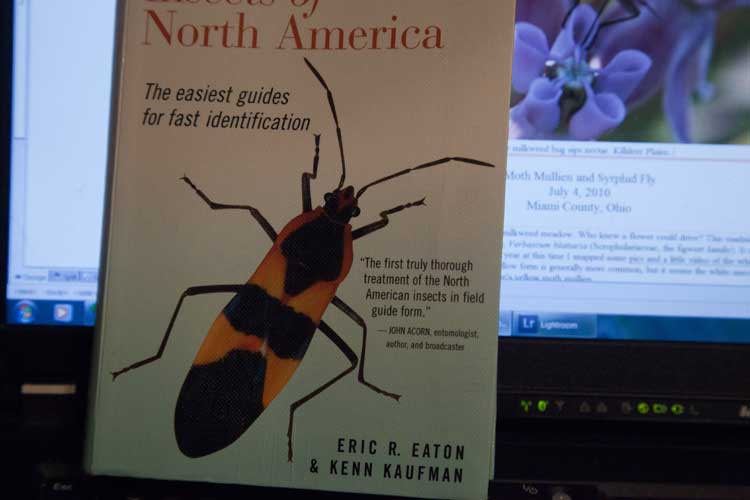

The large milkweed bug is an

especially charismatic insect, as evidenced by the fact that

it's all by itself on the cover of Eaton and Kaufman's excellent

"Insects of North America."

Large milkweed bug is a star! (This is very "meta.")

The milkweed bug is a good example

of a true "bug" in the entomologist's sense, i.e., a member of the

order Hemiptera, a large and diverse group with sucking beak-like

mouthparts tucked beneath the body when not in use, and an

incomplete metamorphosis wherein immatures resemble miniature adults,

but with incompletely developed wings. In their suborder, Heteroptera

(the "original" true bugs), the wings are oriented to give the

insect a very flat-backed appearance, and each forewing is thickened in

its forward half, giving it a somewhat two-toned

appearance.

Here's an action-packed video of a large milkweed bug sipping nectar.

Buggy buggy slurpy slurpy.

Ailanthus webworm moth

sips milkweed nectar. July 19, 2010.

Ailanthus webworm moth

sips milkweed nectar. July 19, 2010.

Here's an action-packed video of a large milkweed bug sipping nectar.

Buggy buggy slurpy slurpy.

Another brightly colored

asclepiavore is a type of longhorn beetle, the red milkweed beetle, Tetraopes tetropthalamus. Eaton and

Kaufman tell us that are 13 species of Tetraopes in North America, and

that "most of the species studied so far specialize on one or a few

species of milkweeds, the larvae mining in the roots, the adults

feeding on the upper foliage and blooms." They do so in a manner the

authors rightly characterize as "boldly in the open by day, their

bright colors advertising their toxic nature." This species, they note,

is the most numerous milkweed beetle in our region, and it feeds

chiefly on common milkweed, Asclepias

syriaca, but has been noted on at least two other Asclepias species. It is

interesting to note that these two extremely bold beetles have

evidently read the book and accordingly selected one of the few A. syrica plants (note the velvet

underleaf) in a sea of Sullivant's.

Another Tetraopes peculiarity that Eaton and Kaufman mention is that "each eye is divided by the antennal socket, hence they are often called 'four-eyed beetles'." It's true.

One of the few easily identified small moths sometimes called "microlepidoptera" is the Ailanthus webworm moth, Atteva punctella. Their larvae occur in communal webs on tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus) trees.

Another Tetraopes peculiarity that Eaton and Kaufman mention is that "each eye is divided by the antennal socket, hence they are often called 'four-eyed beetles'." It's true.

MOUSEOVER the IMAGE for a

ZOOM-CROP showing the nifty FOUR-EYE-NESS

One of the few easily identified small moths sometimes called "microlepidoptera" is the Ailanthus webworm moth, Atteva punctella. Their larvae occur in communal webs on tree-of-heaven (Ailanthus) trees.

Ailanthus webworm moth

sips milkweed nectar. July 19, 2010.

Ailanthus webworm moth

sips milkweed nectar. July 19, 2010.Here's another apparently

non-pollinating insect, a fly, dipping deeply onto a Sullivant's

milkweed hood.

Fly feeding on mikweed nectar at Killdeer Plains. July 14, 2010.

Fly feeding on mikweed nectar at Killdeer Plains. July 14, 2010.

...and here's a video of the fly

feeding.

Fly feeds on milkweed nectar at

Killdeer.

It was an rare treat to see a

lightning bug wandering about on a milkweed umbel. It looks like Photinus pyralus, a common species.

Photinus

firefly on milkweed umbel at Killdeer.

Moth Mullien and Syrphid Fly

July 4, 2010

Miami County, Ohio

I saw a pretty weed driving

to the milkweed meadow. Who knew a flower could drive? This roadside

plant, a native of Eurasia, is moth mullen, Verbascum blattaria

(Scrophulariaceae, the figwort family). It comes in two colors: yellow

and white. Last year at this time I snapped some pics and a

little video of the white form.

According to some sources, the yellow form is generally more common,

but it seems the white ones are more frequent in central Ohio. Here's

yellow moth mullien.

Yellow moth mullien. July 4, 2010. Miami County, Ohio.

Yellow moth mullien. July 4, 2010. Miami County, Ohio.

Moth mullien has

exceptionally long-lived seeds. This was

decisively shown through a wonderful long-running plant ecology

experiment in Michigan, where, in 1879, William

J.

Beals buried 20 vials of soil containing

seeds of 21 different weeds. He developed a

protocol

for

their excavation and viability-testing. The most recent

withdrawls

--there are 5 bottles remaining and the next will be dug up in

2020 --have consistently yielded only moth mullien, plus, in some

instances,

traces of a few other species.

It's called "moth" mullien because its filaments (the anther-supporting stalk portion of the stamens) are plumose, like a moth's antennae. The specific epithet "blattaria" is a reference to roaches, which at one time were thought to be repelled by the plant.

Moth mullien with syrphid fly. July 4, 2010. Miami County, Ohio.

It's called "moth" mullien because its filaments (the anther-supporting stalk portion of the stamens) are plumose, like a moth's antennae. The specific epithet "blattaria" is a reference to roaches, which at one time were thought to be repelled by the plant.

Moth mullien with syrphid fly. July 4, 2010. Miami County, Ohio.

Midnight and Morning Milkweed Marathon

Late June and early July, 2010

Killdeer Plains Wildlife Area, Marion County, Ohio.

Team

Milkweed is hard at

work, discovering what pollinates Sullivant's milkweed (answer:

honeybees),

when the pollination occurs (answer: daytime), and whether

nectar-foraging bees on small clones and large clones differ in whether

they are carrying

pollinia from the same, or different

plants (to be determined).

Team Millweed at Killdeer Plains. June 27, 2010.

Team Millweed at Killdeer Plains. June 27, 2010.

Since Milkweed Midsummer is a

longstanding tradition, a description of Sullivant's

milkweed can be found here, and

more detailed information about its pollnation is here.

This summer, the focus is more on the broader pollination ecology of the species rather than just its breeding system and potential for hybridization, so we are noticing more insect species exploiting these beautiful plants. This, for example, is not what it looks like, unless it looks like a fly that looks like a bee. It's a type of flower-fly (Order Diptera; Family Sirphidae) that is a bumblebee-mimic, most likely Mallota bautias.

Mallota flower fly forages on milkweed at Killdeer. June 27, 2010.

This summer, the focus is more on the broader pollination ecology of the species rather than just its breeding system and potential for hybridization, so we are noticing more insect species exploiting these beautiful plants. This, for example, is not what it looks like, unless it looks like a fly that looks like a bee. It's a type of flower-fly (Order Diptera; Family Sirphidae) that is a bumblebee-mimic, most likely Mallota bautias.

Mallota flower fly forages on milkweed at Killdeer. June 27, 2010.

Milkweed flowers don't ever

close, so do night-time nectar feeders seek

nectar from them? Indeed, there have been studies showing a small but

substantial amount of nocturnal pollination of

the closely related common milkweed, Asclepias

syriaca.

Our day/night study involves placing mesh bags over the flower clusters

that prevent insect access to them during either the daytime or the

nightime. Here's a night-flying moth that seemed more interested in the

bagged flowers than all the others nearby. It may be a type of owlet

moth, i.e., a member of the lepidopteran Family Nolidae (formerly

included in Noctuidae).

Nolid moth on nylon pollinator exclusion bag. July 1, 2010.

Nolid moth on nylon pollinator exclusion bag. July 1, 2010.

While generally the blossoms

are ignored at night, a few visitors show up. Here's another nolid moth

and, if you look closely, there are at least two of what I guess are

male mosquitoes, because they have plumose antennae and are feeding on

nectar.

MOUSEOVER IMAGE for ZOOM-CROP of

MALE MOSQUITO

Nolid moth and male

mosquitoes sup on milkweed nectar. July

1, 2010.

Note also a snagged honeybee in the background at the upper edge of the photo.

Note also a snagged honeybee in the background at the upper edge of the photo.

While prowling around at

night it was nice to see a monarch chrysalis on yellow fox sedge (Carex annectans). These "emerald

houses with golden nails" are quite common this summer.

Monarch butterfly chrysalis. July 1, 2010.

Here's the same sedge in the daylight.

Yellow fox sedge with monarch chrysalis. July 1, 2010.

It is intriguing and informative to observe a variety of insects, day and night, on Sullivant's milkweed blossoms. Nonetheless, many hours of observation indicate that just one insect, a non-native species, the honeybee, is practically its only pollinator at Killdeer Plains. Here's one foraging; note the little yellowish pollinaria attached to her feet.

Honeybee forages on Milkweed at Killdeer. July 10, 2010.

There are a few other milkweed species in the area. One of them, whorled milkweed, Asclepias verticillata, has such small flowers and a small stature, that it is easy to miss.

Whorled milkweed at Killdeer. July 2, 2010.

Whorled milkweed at Killdeer. July 2, 2010.

Monarch butterfly chrysalis. July 1, 2010.

Here's the same sedge in the daylight.

Yellow fox sedge with monarch chrysalis. July 1, 2010.

It is intriguing and informative to observe a variety of insects, day and night, on Sullivant's milkweed blossoms. Nonetheless, many hours of observation indicate that just one insect, a non-native species, the honeybee, is practically its only pollinator at Killdeer Plains. Here's one foraging; note the little yellowish pollinaria attached to her feet.

There are a few other milkweed species in the area. One of them, whorled milkweed, Asclepias verticillata, has such small flowers and a small stature, that it is easy to miss.

Whorled milkweed at Killdeer. July 2, 2010.

Whorled milkweed, while

scarce at Killdeer, is exceedingly abundant in some parts of

northwestern Ohio, where it is a weed, for example along interstate

highway I-75 in Wood County. The blossoms are tiny, but with the same

flower structure as its larger congenors.

Whorled milkweed at Killdeer. July 2, 2010.