(Additional content at flickr Photostream and YouTube Channel)

If you have botany questions or comments please email BobK . Thanks!

Kempton, PA.

October 11, 2009

Located in east-central Pennsylvania, Hawk Mountain Sanctuary is one of the best places in the world to see migrating raptors. Our family goes there practically every year, usually in late September, but this time we went in October. We saw hawks, many of them, some quite close. But none were as close as the plants which, unlike hawks, politely pose to have their pictures taken.

An understory maple that is very common in northern-montane areas, including here in the Kittaninny Ridge of the Appalachians, is, in Ohio, a rare plant found only in the extreme northeast corner of the state. Thus it is a treat to see striped maple, Acer pensylvanicum (family Aceraceae). The leaves are large, and tri-lobed.

Striped maple. Hawk Mt. Kempton, PA. October 11, 2009.

Although this specimen

doesn't show it very markedly, the bark is indeed striped.

Slightly striped maple bark.

Hawk. Mt. PA. Oct. 11, 2009.

Slightly striped maple bark.

Hawk. Mt. PA. Oct. 11, 2009.

Another understory tree,

quite common in Ohio as well as here, is witch-hazel, Hamamelis virginiana

(family Hamamelidaceae). It's in full bloom now, producing scraggly

blossoms, each with with 4 linear petals. Witch hazel bark is the

source of the famous astingent lotion used to treat sore muscles.

Witch-hazel flower. Hawk Mt., PA. October 11, 2009.

Some lovely and fairly easily recognized woodland goldenrods (genus Solidago, family Asteraceae) are still in bloom. Both differ from other goldenrods in that their flowers are positioned in the axils of leaves, along the stem. One of these, zigzag goldenrod, S. flexicaulis, has especially broad leaves with a winged petiole (leafstalk).

Zigzag goldenrod. Hawk Mt. PA. October 11, 2009.

Witch-hazel flower. Hawk Mt., PA. October 11, 2009.

Some lovely and fairly easily recognized woodland goldenrods (genus Solidago, family Asteraceae) are still in bloom. Both differ from other goldenrods in that their flowers are positioned in the axils of leaves, along the stem. One of these, zigzag goldenrod, S. flexicaulis, has especially broad leaves with a winged petiole (leafstalk).

Zigzag goldenrod. Hawk Mt. PA. October 11, 2009.

The other, blue-stemmed

goldenrod, S. caesia, has

narrow leaves.

Blue-stemmed goldenrod. Hawk. Mt. PA. October 11, 2009.

Blue-stemmed goldenrod. Hawk. Mt. PA. October 11, 2009.

A fern with delicate leaves

that is common in open areas is hay-scented fern, Dennstaedtia punctilobula

(Dennstaedtiaceae). Spreading by means of a horizontal (creeping)

rhizome, it can cover whole hillsides.

Hay-scented fern. Hawk Mt. Kempton, PA. October 11, 2009.

Hay-scented fern. Hawk Mt. Kempton, PA. October 11, 2009.

The sori of Dennstaedtia are small, and located

at the margins of the leaflets.

Hay-scented fern sori. Hawk Mt. PA. October 11, 2009.

Hay-scented fern sori. Hawk Mt. PA. October 11, 2009.

Some Common Corticolous Mosses

(originally published in OBELISK, the newsletter of the

Ohio Moss and Lichen Association )

www.ohiomosslichen.org

In Ohio’s deciduous forests,

standing trees are an important habitat for mosses. Corticolous

(bark-inhabiting) mosses tend to be especially abundant at the bases of

trees, where moisture and nutrients are not as scarce as they are

higher up on the trunk. Mat-forming pleurocarps (carpet mosses) do well

at tree bases. Perhaps the most abundant low bark-inhabiting moss is

Anomodon attenuatus (family Leskaceae). This species is distinctive on

many scales. From afar, a tree sporting a lush growth of this moss

around its swollen base looks like a giant leg wearing a sporty green

ankle sock (albeit one that is slightly frayed).

Anomodon attenuatus adorns the base of tree

Anomodon attenuatus adorns the base of tree

Close-up, note the drooping

tapered branches, the basis of the specific epithet “attenuatus.”

Anomodon attenuatus has drooping tapered branches.

Anomodon attenuatus has drooping tapered branches.

Another primarily epiphytic

member of the Leskeaceae frequenting the zone from tree base up to

eye-level on trunks, and extending out onto lower branches as well, is

Leskea gracilescens. It seems to be most abundant in floodplain

forests.

Leskea gracilescens grows in dense mats.

Leskea gracilescens grows in dense mats.

Leskea

is a small moss with branches that are neither flattened nor tapered.

When dry, the leaves hug the stem. Microscopically, note the prominent

single costa (midvein) and stoutly unipapillose leaf cells.

Leskea gracilescens through the microscope.

Inset: papillose leaf cells.

Leskea gracilescens through the microscope.

Inset: papillose leaf cells.

Unlike the tree-base and

low-level trunk dwellers, which tend to occur on logs and rocks as

well, most of the mosses that occur high on trees tend to occur only on

trees. Several are tufted acrocarps (cushion mosses). One prominent

high-bark genus is Orthotrichum,

(family Orthotrichaceae), looking like small dark fingers extending out

perpendicularly from the bark.

Orthotrichum pumilum has erect leaves.

Orthotrichum pumilum has erect leaves.

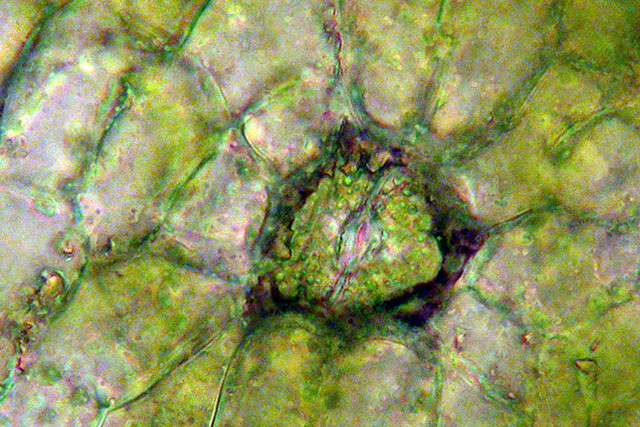

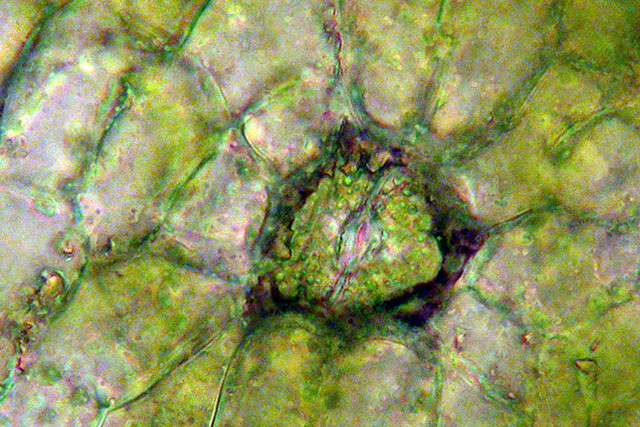

While the genus may be easy

to spot, species identification hinges on some technical features of

the sporophyte that can be a challenge to ascertain, including the

degree to which the capsules are ridged when dry, and whether the

stomates are superficial or immersed. (Who even knew that non-vascular

plants have stomates?) And, if immersed, whether the cells surrounding

the stomates jut up or instead lay flat. Am I the only naturalist

occasionally struck with skepticism that apparently subjective and

variable traits used to separate some species reflect genuine patterns

in nature? Anyhow, here’s a picture of an Orthotrichum stomate, of the

immersed sort, surrounding cells not jutting upwards.

Orthotrichum stomate (breathing pore)

Orthotrichum stomate (breathing pore)

Another member of the

Orthotrichaceae, also a small high-bark cushion moss, is Ulota crispa. (A second Ulota species occurs in Ohio, but

is quite rare.) This moss is distinctive when dry, as it has very

curly-twisted leaves.

Ulota crispa has curled leaves.

Ulota crispa has curled leaves.

One of the few mosses to have

a common name, Anacamtodon

splachnoides

(family Fabroniaceae) is the “knothole moss.” It’s a nondescript

pleurocarp that Crum and Anderson, in “Mosses of Eastern North America”

say resembles “a large-scale Amblystegium with leaves tending to be

upturned rather than evenly spreading on all sides of the branches.”

Its capsules, erect and sharply constricted below the mouth, are

distinctive. As per the common name, Anacamptodon

is a denizen of moist, soft or rotten bark.

Anacamptodon is the knothole moss

Anacamptodon is the knothole moss

Not all corticolous mosses

are strict forest-dwellers. A genus that includes some species notable

for being more common on roadside trees in the city is Tortula

(family Pottiaceae). These are beautiful little acrocarps with broad

long-awned leaves that, when wet, spread widely, giving the plant a

rose-like appearance. In Ohio, two species occur, both of which, in

North America, reproduce only asexually. They are readily distinguished

by their propagula. T. papillosa,

a fairly common species, bears abundant globose few-celled ones, while

T. pagorum, reported from only 6 counties, has leaf-like propagula.

According to Crum and Anderson, only female T. pagorum

plants have been found in North America while in Europe there are only

male plants. The only fruiting individuals were described from

Australia!

Tortula pagorum & T. papillosa

reproduce asexually.

Tortula pagorum & T. papillosa

reproduce asexually.

This short article mentions

just a few of our more common tree-hugging mosses. When out hunting for

these interesting plants, keep an eye out for some of Ohio’s rarer

mosses. Neckera pennata

(family Neckeraceae), for example, is known from only three counties.

Neckera has flattened shelf-like branches that spread from the trunks

of trees, bearing shiny undulate leaves. It would be a thrill to see!

Serendipitous Traveling Botanical Reserve

Columbus, Ohio. October 2, 2009

In eager anticipation of the

Fantastic Filmy Fern Foray (below), I stopped at a local grocery for

provisions. Parked next to me was a pickup truck with a single

bag

of coarse sand in its bed. The sand-bag evidently split open some time

ago, and nature reigns freely --a wilderness area!

Pickup truck and asociated vegtetation (circled). October 2, 2009.

Pickup truck and asociated vegtetation (circled). October 2, 2009.

The recognizable species

present, some of them flowering, are horseweed

(Conyza canadensis, family

Asteraceae), crabgrass (Digitaria sp., Poaceae), dandelion (Taraxacum officinale, Asteraceae), lamb's-quarters (Chenopodium album, Chenopodiaceae),

and common sow-thistle (Sonchus oleraceus, Asteraceae).

Traveling botanical wilderness area. Columbus, Ohio. Oct. 2, 2009.

Traveling botanical wilderness area. Columbus, Ohio. Oct. 2, 2009.

Horseweed is a native annual

closely related to, and sometimes considered congeneric with, fleabanes

in the genus Erigeron.

A troublesome agricultural weed, it is becoming more so as

glyphosate-resistant populations have evolved where soybeans are grown

in the same field year after year with little tillage, using only

glyphosate as weed control.

Crabgrass, while not the manicured-lawn-lover's best friend, has some useful relatives. One is "white fonio" (Digitaria exilis), a fast-growing small-seeded millet grown in dry regions of Africa, including southern Sudan and Ethiopia. Crabgrasses, like maize, are able to tolerate dought because they have an especially efficient photosynthetic mechanism called "C-4 photosynthesis." C-4 plants use an enzyme, PEP carboxylase, that more aggresively extracts carbon dioxide from the air than does the enzyme that non-C-4 plants use. Water loss through the plant's stomates (breathing pores) is thus minimized because they don't have to be open so much.

The name dandelion is a corruption of French dent de lion, as the sharp-lobed leaves look ferociously tooth-like.

Lamb's-quarters is a close relative of spinach and is a popular wild edible plant, prepared as you would spinach. Would it be effective for Popeye?

Sow-thistle is a close relative of lettuce and is a popular wild edible plant, prepared as you would lettuce. Would it be good with olive-oil?

Crabgrass, while not the manicured-lawn-lover's best friend, has some useful relatives. One is "white fonio" (Digitaria exilis), a fast-growing small-seeded millet grown in dry regions of Africa, including southern Sudan and Ethiopia. Crabgrasses, like maize, are able to tolerate dought because they have an especially efficient photosynthetic mechanism called "C-4 photosynthesis." C-4 plants use an enzyme, PEP carboxylase, that more aggresively extracts carbon dioxide from the air than does the enzyme that non-C-4 plants use. Water loss through the plant's stomates (breathing pores) is thus minimized because they don't have to be open so much.

The name dandelion is a corruption of French dent de lion, as the sharp-lobed leaves look ferociously tooth-like.

Lamb's-quarters is a close relative of spinach and is a popular wild edible plant, prepared as you would spinach. Would it be effective for Popeye?

Sow-thistle is a close relative of lettuce and is a popular wild edible plant, prepared as you would lettuce. Would it be good with olive-oil?

Fantastic Filmy Fern Foray

Hocking, Athens, and Jackson Counties, Ohio

October 3, 2009

Brian

Gara, a field botanist with considerable expertise in ferns, generously

offered to guide several fernophilic friends to a spot near his alma mater, Ohio University in

Athens, Athens County, Ohio, to see the most marvelous

thing that nature ever selected, "weft fern," Trichomanes intricatum.

Weft fern. It looks like green hair. Is this really a fern?

It looks like green hair. Is this really a fern? Answer: yes, and no. Weft fern is certainly a fern in the phylogenetic (taxonomic) sense of where it is placed in the plant kingdom, but morphologically it is what for most ferns is only a transitory stage --the gametophyte generation --that normally gives rise to the leafy sporophyte generation we usually mean by "fern." Like the "Appalachian gametophyte," (Vittaria appalachiana in the "shoestring fern" family Vittariaceae), weft fern is a persistent asexually reproducing fern gametophyte for which the sporophyte generation apparently no longer exists!

Weft fern is one of Ohio's two members of the filmy fern family, Hymenophyllaceae. The other is Applachian filmy fern, T. boschianum, about which more below. This mainly tropical family consists of very delicate ferns, the leaves of which are only one cell thick. In our region, filmy ferns are restricted to deep, perennially moist, rock recesses that are sheltered from prolonged temperature extremes and competition from most other plants. In a summary of the family in the Flora of North America, noted pteridologist Donald Farrar, who described T. intricatum in 1992, explains that their delicate nature is probably the main reason for their rarity. Like the Appalachian gametophyte, the filmy ferns may have been more widespread before the Plesistocene glaciations. They were able to persist during that very hard time to be a fern (brrrr) by the capacity for their gametophyte generation to hide in protected niches and undergo vegetative reproduction.

Along on the Fantastic Filmy Fern Foray was Cynthia Dassler, Curator of Cryptogams at the OSU Herbarium. Cynthia was one of Donald Farrar's Ph.D. students, and is an authority on the form, function and significance of gametophytes in the Hymenophyllaceae. Also, Cynthia having recently communicated with Dr. Farrar about significant fern locations in southern Ohio, we charted a course for an intriguing spot in Jackson County where Don once saw sprophytes --abortive little poorly-formed sprotophytes to be sure, but sporophytes nonetheless --of the Appalachian gametophyte. (We didn't see them, but were rewarded with good mosses!)

About halfway down Rte 33 on the way to Athens, Brian remarked that we were not far from a station for the Appalachian filmy fern, Trichomanes boschianum, in eastern Hocking County. "Let's go!" we all chanted. With assistance from the Google Maps "app" on the i-phone (a close contender for the greatest thing that nature ever selected) we found the spot, at a T-shaped intersection of two rather rural roads.

The filmy fern lives in a deep recess in a sandstone overhang, what is known locally as a "rockhouse," more widely known as a "grotto."

Brian and Cynthia examine filmy fern habitat in Hocking County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

The rockhouse is dark. A flashlight comes in handy.

Looking for filmy fern at Hocking County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Weft fern. It looks like green hair. Is this really a fern?

It looks like green hair. Is this really a fern? Answer: yes, and no. Weft fern is certainly a fern in the phylogenetic (taxonomic) sense of where it is placed in the plant kingdom, but morphologically it is what for most ferns is only a transitory stage --the gametophyte generation --that normally gives rise to the leafy sporophyte generation we usually mean by "fern." Like the "Appalachian gametophyte," (Vittaria appalachiana in the "shoestring fern" family Vittariaceae), weft fern is a persistent asexually reproducing fern gametophyte for which the sporophyte generation apparently no longer exists!

Weft fern is one of Ohio's two members of the filmy fern family, Hymenophyllaceae. The other is Applachian filmy fern, T. boschianum, about which more below. This mainly tropical family consists of very delicate ferns, the leaves of which are only one cell thick. In our region, filmy ferns are restricted to deep, perennially moist, rock recesses that are sheltered from prolonged temperature extremes and competition from most other plants. In a summary of the family in the Flora of North America, noted pteridologist Donald Farrar, who described T. intricatum in 1992, explains that their delicate nature is probably the main reason for their rarity. Like the Appalachian gametophyte, the filmy ferns may have been more widespread before the Plesistocene glaciations. They were able to persist during that very hard time to be a fern (brrrr) by the capacity for their gametophyte generation to hide in protected niches and undergo vegetative reproduction.

Along on the Fantastic Filmy Fern Foray was Cynthia Dassler, Curator of Cryptogams at the OSU Herbarium. Cynthia was one of Donald Farrar's Ph.D. students, and is an authority on the form, function and significance of gametophytes in the Hymenophyllaceae. Also, Cynthia having recently communicated with Dr. Farrar about significant fern locations in southern Ohio, we charted a course for an intriguing spot in Jackson County where Don once saw sprophytes --abortive little poorly-formed sprotophytes to be sure, but sporophytes nonetheless --of the Appalachian gametophyte. (We didn't see them, but were rewarded with good mosses!)

FFFF

Part One: Filmy Fern in Hocking County

About halfway down Rte 33 on the way to Athens, Brian remarked that we were not far from a station for the Appalachian filmy fern, Trichomanes boschianum, in eastern Hocking County. "Let's go!" we all chanted. With assistance from the Google Maps "app" on the i-phone (a close contender for the greatest thing that nature ever selected) we found the spot, at a T-shaped intersection of two rather rural roads.

The filmy fern lives in a deep recess in a sandstone overhang, what is known locally as a "rockhouse," more widely known as a "grotto."

Brian and Cynthia examine filmy fern habitat in Hocking County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

The rockhouse is dark. A flashlight comes in handy.

Looking for filmy fern at Hocking County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Deep in the crevice, a thriving population of filmy fern sporophytes.

Filmy fern population at Hocking County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Seen

close-up, the delicate

nature of this fern may be evident. In real life it doesn't look so

glowing and luminescent. The extreme reflectivity in the photos is

"specular highlights," an annoying side effect of using flash.

Filmy fern in Hocking County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Filmy fern in Hocking County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Alongside the fern, another

rare denizen of the moist acidic shady niches that are free

from temperature extremes, "sword moss" Bryoxiphium norvegicum

(Bryoxiphiaceae).

Sword moss at Hocking County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

FFFF Part 2: Weft Fern at Athens

Brian confirms location of weft fern in Athens, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

The site is remarkably like the filmy fern station, a deep

dark recess in a sandstone cliff.

Weft fern habitat in Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Sword moss at Hocking County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

FFFF Part 2: Weft Fern at Athens

The Athens weft fern location

is a large wooded area with

dissected topography in Hawk Woods (Riddle State Nature Preserve).

Being

pretty wilderness-ey, it was helpful to have GPS coordinates, and an

expert in using them.

Brian confirms location of weft fern in Athens, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Weft fern habitat in Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

...and is likewise rendered

more visible by the use of a "torch." (That's what they call a

flashlight in England.)

Looking for weft fern in Athens, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Looking for weft fern in Athens, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

It was so dark that my first

attempt at weft fern photography missed the mark. Instead of a patch of

weft fern I managed to snap a moss, probably Isopterygium elegans (family

Hypnaceae), with a little bit of weft fern mixed in.

A moss, possibly Isopterygium elegans, at Athens, Ohio., October 3, 2009.

A moss, possibly Isopterygium elegans, at Athens, Ohio., October 3, 2009.

For what it's worth, here's

weft fern in all its glory.

Weft fern, Trichomanes intricatum, at Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Weft fern, Trichomanes intricatum, at Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

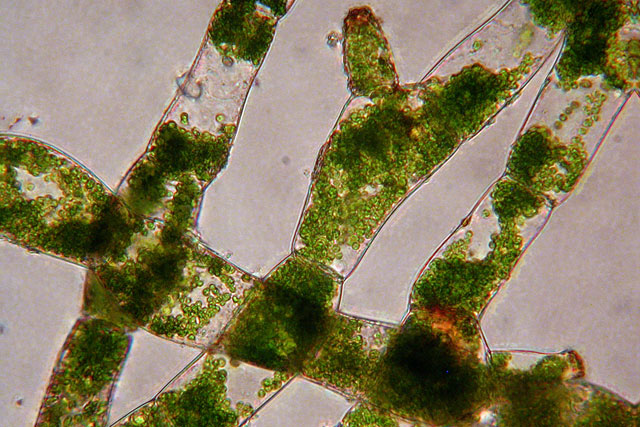

It's hard to believe this is

a fern, even though it's not, exactly, in the usual sense of the word,

a fern. It's a fern gametophyte.

Even so, most fern gametophytes are little heart-shaped things, not

filamentous ones. Except for the fact that, apparently, there aren't

any actual filamentous green algae that look much like weft fern, weft

fern

looks like a filamentous green alga.

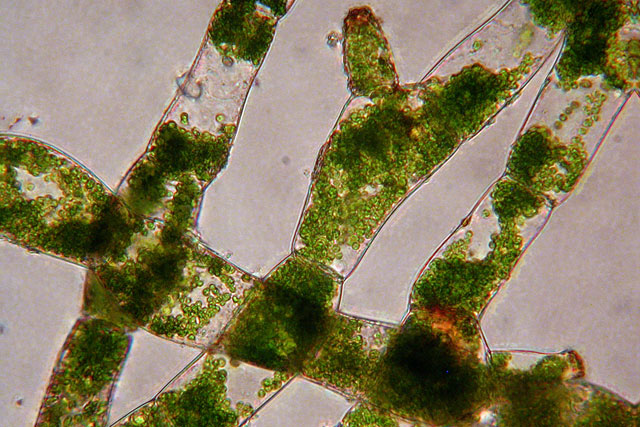

A tiny little piece jumped into my pocket and when I got home I looked at it under the microscope, to see if there is anything distinctive about it. Not really. It looks like a filamentous green alga, except that it doesn't. Here's a link to some other weft fern pictures, including macro- and microscopic views. The pictures match. Very satisfying!

Weft fern, microscope view.

A tiny little piece jumped into my pocket and when I got home I looked at it under the microscope, to see if there is anything distinctive about it. Not really. It looks like a filamentous green alga, except that it doesn't. Here's a link to some other weft fern pictures, including macro- and microscopic views. The pictures match. Very satisfying!

Weft fern, microscope view.

Recently

there have been some surprising findings from an analysis of weft fern

DNA that has raised questions about its origin. In a 2008

article in American Journal of Botany

entitled "THE SPOROPHYTE-LESS FILMY FERN OF EASTERN NORTH AMERICA TRICHOMANES INTRICATUM

(HYMENOPHYLLACEAE) HAS THE CHLOROPLAST GENOME OF

AN ASIAN SPECIES, Atsushi Ebihara, Donald R. Farrar, and

Motomi Ito report a stong genetic similarity between weft

fern's chloroplast genome and that of an Asian fern, Crepidomanes schmidtianum.

The Results section opens with the provocative statement "Sporophytes

of all Crepidomanes species are confined to the Old World; however, it

appears that one of the species, in the form of independently growing

gametophytes, has reached the New World."

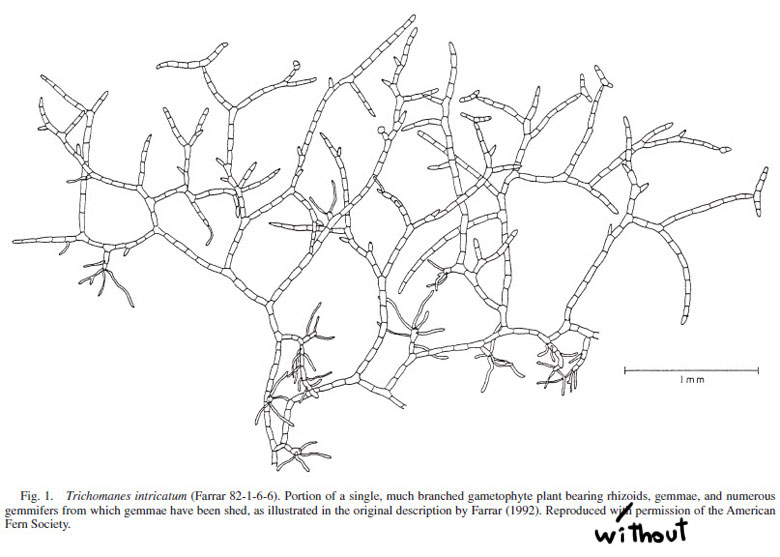

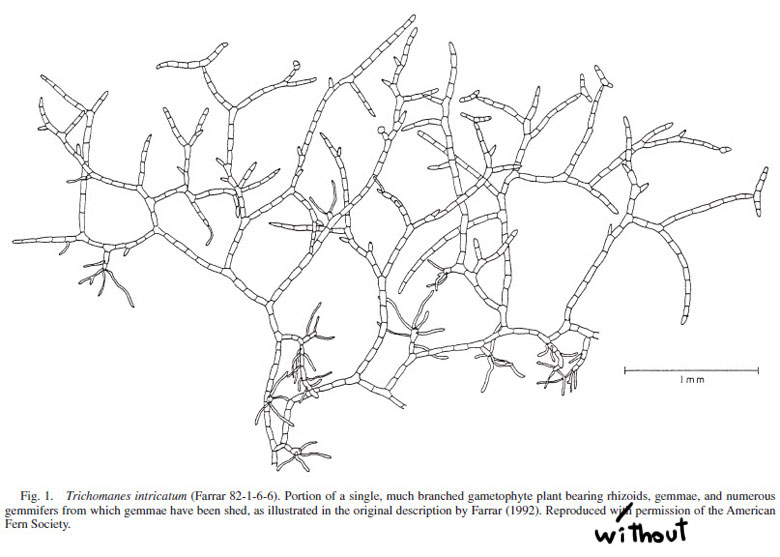

The article also includes a great photo of Old man's Cave, and a nice reprint of Farrar's original line drawing of weft fern. Let's hope the lawyers for the American Fern Society have bigger fish to fry, because here comes an instance of egregious copyright infringement:

Eastern Asian/eastern North American disjunct species distributions, including occurences in these widespread locations of closely related species pairs, are numerous and have been studied for many years. These seemingly anomolous distributions are generally attributed to there having been a greater development of temperate forests in the northern hemisphere during the Tertiary Period, and the involvement of both the North Atlantic and the Bering land bridges. Jun Wen, in a 1999 Annual Review of Evolution and Systematics (30: 421-455) paper entitled EVOLUTION OF EASTERN ASIAN AND EASTERN NORTH AMERICAN DISJUNCT DISTRIBUTIONS IN FLOWERING PLANTS, states that "In many genera of flowering plants, current estimates of divergence times using molecular and fossil data suggest that the disjunct patterns were established during the Miocene. Morphological stasis, evidenced by the minimal morphological divergence of species after a long time of separation, must have occurred in some of the disjunct groups in the north temperate zone.

But for the weft fern, Ebihara et al. note, interestingly, that the similarity between its choroplast genome and that of the Asian Crepidomanes species is much greater than that normally observed for Asian/North American disjunct fern populatioins. Therefore the event separating these two must have taken place quite recently. Because the weft fern's gemmae (asexual reproductive structures) are kind of clunky (my words), they probably were not able to facilitate long-distance dipersal from Asia to the Appalachians. Is spore disperal the likely agent? Normally that would seem likely, but C. schmidtianum apparently has a peculiar chromsomal complement -- it is triploid, i.e. it has three sets of chromosomes. Being triploid is a roadblock to sexual reproduction, because odd numbers of chromosome sets cannot form the neat pairs that must form when nuclei undergo meiosis. (Meiosis is the halfing of chromosome number that happens when spores are formed, and is a necessary prerequisite to the blending of genomes in any sexual life cycle.) If, therefore, as seems likely, triploid Credidomanes cannot form viable spores, long-distance spore dipersal cannot account for trans-Pacific dispersal of the plant.

Yikes, this is getting WAY too wordy for what is supposed to be a lighthearted photography web site, so here's a picture of absinthe dental floss alongside a scary plastic model of a red pepper.

Regarding weft fern, so far, so bad. To summarize: (1) the too-close genetic similarity of it and the Asian Crepidomonas rules out a Tertiary Period separation of a formerly contiguous Asian/North American population, and (2) the sterility of C. schmidtianum rules it out as as the progenitor of weft fern via long-distance dispersal from eastern Asia. So what's left? Perhaps dual origins, involving hybridization! Drawing on the fact that chloroplasts are contained within the cytoplasm of the cell and are thus transmitted only along the maternal line, the AJB article suggests that "...intriguing possibilities are that T. intricatum and C. schmidtianum were produced by independent hybrid events involving the same female parent, and thus the same chloroplast genome. T. intricatum could also be the female parent of triploid C. schmidtianum. The latter hypothesis allows the possibility of an ancestral T. intricatum, with normal alternation of generations, attaining an amphipacific range via spore dispersal, then becoming confined to eastern North America and losing its sporophyte generation."

There were some nice normal ferns --sporophytes --at Hawk Woods. Here are some of them.

Goldies's Fern, Dryopteris goldiana (family Dryopteridaceae), an especially robust woodfern, is an uncommon inhabitant of rich woods.

Goldie's Fern at Hawk Woods, Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

The article also includes a great photo of Old man's Cave, and a nice reprint of Farrar's original line drawing of weft fern. Let's hope the lawyers for the American Fern Society have bigger fish to fry, because here comes an instance of egregious copyright infringement:

Illustration of weft fern,

originally from Farrar , D. R. 1992 . Trichomanes

intricatum: The independent Trichomanes gametophyte in the eastern

United States. American Fern Journal 82 : 68 – 74.

Eastern Asian/eastern North American disjunct species distributions, including occurences in these widespread locations of closely related species pairs, are numerous and have been studied for many years. These seemingly anomolous distributions are generally attributed to there having been a greater development of temperate forests in the northern hemisphere during the Tertiary Period, and the involvement of both the North Atlantic and the Bering land bridges. Jun Wen, in a 1999 Annual Review of Evolution and Systematics (30: 421-455) paper entitled EVOLUTION OF EASTERN ASIAN AND EASTERN NORTH AMERICAN DISJUNCT DISTRIBUTIONS IN FLOWERING PLANTS, states that "In many genera of flowering plants, current estimates of divergence times using molecular and fossil data suggest that the disjunct patterns were established during the Miocene. Morphological stasis, evidenced by the minimal morphological divergence of species after a long time of separation, must have occurred in some of the disjunct groups in the north temperate zone.

But for the weft fern, Ebihara et al. note, interestingly, that the similarity between its choroplast genome and that of the Asian Crepidomanes species is much greater than that normally observed for Asian/North American disjunct fern populatioins. Therefore the event separating these two must have taken place quite recently. Because the weft fern's gemmae (asexual reproductive structures) are kind of clunky (my words), they probably were not able to facilitate long-distance dipersal from Asia to the Appalachians. Is spore disperal the likely agent? Normally that would seem likely, but C. schmidtianum apparently has a peculiar chromsomal complement -- it is triploid, i.e. it has three sets of chromosomes. Being triploid is a roadblock to sexual reproduction, because odd numbers of chromosome sets cannot form the neat pairs that must form when nuclei undergo meiosis. (Meiosis is the halfing of chromosome number that happens when spores are formed, and is a necessary prerequisite to the blending of genomes in any sexual life cycle.) If, therefore, as seems likely, triploid Credidomanes cannot form viable spores, long-distance spore dipersal cannot account for trans-Pacific dispersal of the plant.

Yikes, this is getting WAY too wordy for what is supposed to be a lighthearted photography web site, so here's a picture of absinthe dental floss alongside a scary plastic model of a red pepper.

Absinthe (derived from Artemisia absinthium, family

Asteraceae) dental floss.

Regarding weft fern, so far, so bad. To summarize: (1) the too-close genetic similarity of it and the Asian Crepidomonas rules out a Tertiary Period separation of a formerly contiguous Asian/North American population, and (2) the sterility of C. schmidtianum rules it out as as the progenitor of weft fern via long-distance dispersal from eastern Asia. So what's left? Perhaps dual origins, involving hybridization! Drawing on the fact that chloroplasts are contained within the cytoplasm of the cell and are thus transmitted only along the maternal line, the AJB article suggests that "...intriguing possibilities are that T. intricatum and C. schmidtianum were produced by independent hybrid events involving the same female parent, and thus the same chloroplast genome. T. intricatum could also be the female parent of triploid C. schmidtianum. The latter hypothesis allows the possibility of an ancestral T. intricatum, with normal alternation of generations, attaining an amphipacific range via spore dispersal, then becoming confined to eastern North America and losing its sporophyte generation."

There were some nice normal ferns --sporophytes --at Hawk Woods. Here are some of them.

Goldies's Fern, Dryopteris goldiana (family Dryopteridaceae), an especially robust woodfern, is an uncommon inhabitant of rich woods.

Goldie's Fern at Hawk Woods, Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Glade fern, Diplazium (formerly Athyrium) pycnocarpon (Dryopteridaceae), is

an an uncommon once-pinnate fern that superficially resembles the much

more common Christmas Fern.

Glade Fern at Hawk Woods, Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Glade Fern at Hawk Woods, Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Unlike Christmas fern, which

bears spores underneath shrunken leaflets restricted to

the tops of the fronds, glade fern has large linear sori beneath

otherwise normal leaflets, found all up and down the rachis.

Glade Fern at Hawk Woods, Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Glade Fern at Hawk Woods, Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Broad beech fern, Phegopteris (formerly Thelypteris) hexagonaptera (Thelypteridaceae) is

a small pinnate-pinnatifid fern with an overall triangular outline.

Broad beech fern at Hawk Woods, Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

FFFF Part 3: Hunting in vain for the Appalachian Sporophyte

Broad beech fern at Hawk Woods, Athens County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

FFFF Part 3: Hunting in vain for the Appalachian Sporophyte

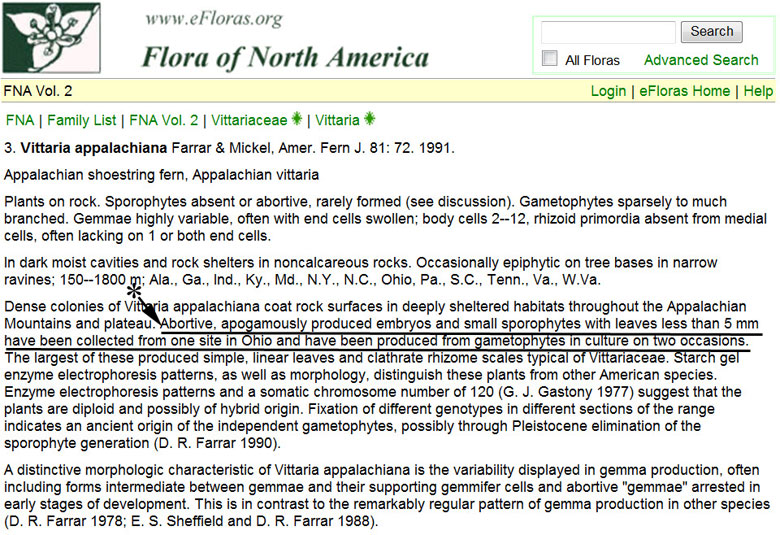

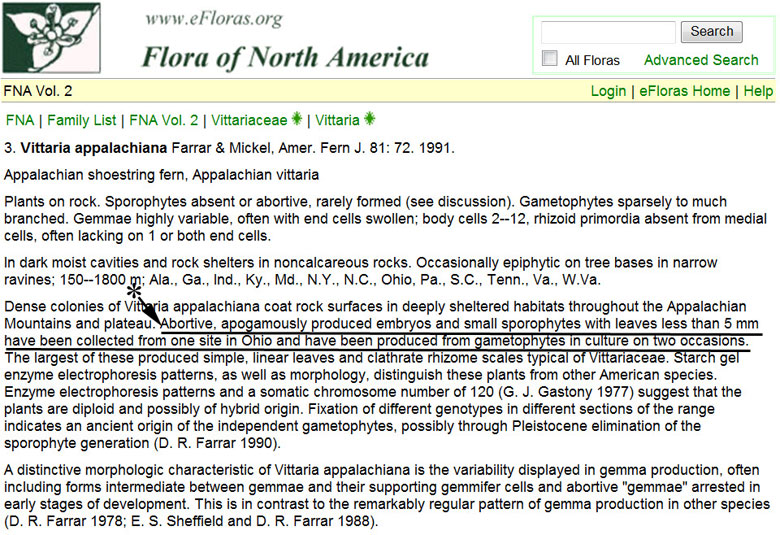

The other, and much more

well-known sporophyte-less fern is, of course, the "Appalachian

gametophyte," Vittaria appalachiana.

And Cynthia, in a recent conversation with Donald Farrar, was given the

location of the site in Ohio referenced below in his Flora of North America entry,

where once he found abortive, apogamously produced embryos and small

sporophytes.

The site is in nearby Jackson

County, alongside "old" Rte. 35, six miles east of the Ross County

line.

We decided to give it a try. The search was fruitless insofar

as the elusive sporophytes were concerned, but was fun and surprising

nonetheless. Once again we visited stepped sandstone cliffs with deep

recesses.

Bill and Jeff search for sporophytes in Jackson County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Bill and Jeff search for sporophytes in Jackson County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

The fun surprise here was

seeing wetland plants on a cliff in the forest! Apparently the upper

lips of the sandstone ledges trap some water that flows down them or

through them, resulting in patches of persistently saturated soil. In

the central portion of the view below, the grayish green cover is...

Moist-lipped micro-wetland ledge in Jackson County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Moist-lipped micro-wetland ledge in Jackson County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

...sphagnum moss! Huh?

Sphagnum,

also called "peat moss," is normally thought of as a mat-forming

genus of acid bogs that is especially abundant in boreal regions. But

clumps of Sphagnum

occassionally occur in less extensive wet places. Judging from species

descriptions --we eventually identified this one as Sphagnum lescurii --woodland

rock-ledge occurences of Sphagnum

aren't really all that rare. For example, Jerry Snider, in a bryophyte

survey of Crane Hollow in Hocking County, recorded five Sphagnum species on thin soil over

sandstone.

Sphagnum lescurii (and Thuidium delicatulum) on thin soil over sandstone, Jackson County, Ohio.

Sphagnum lescurii (and Thuidium delicatulum) on thin soil over sandstone, Jackson County, Ohio.

Basically a swamp plant, here

we see royal fern, Osmunda regalis

(family Osmundaceae), growing on a rocky ledge in the woods.

Royal fern on a sandstone ledge, jackson County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Royal fern on a sandstone ledge, jackson County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Another fern, more typical

for a sandstone ledge, is mountain spleenwort, Asplenium montanum (Aspleniaceae).

Fuzzy caterpillar crawls over mountain spleenwort at Jackson County, Ohio, October 3, 2009.

Fuzzy caterpillar crawls over mountain spleenwort at Jackson County, Ohio, October 3, 2009.

Blunt-lobed cliff fern, Woodsia obtusa

(family Dryopteridaceae) is a delicate fern that, according to the

books, is supposed to occur in limestone areas, so its occurrence here

in sandstone-land is a bit surprising.

Blunt-lobed Woodsia at Jackson County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Blunt-lobed Woodsia at Jackson County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Underneath, we see fairly

large clusters of sporangia, helpful to distinguish this genus from the

somewhat similar fragile ferns (Cystopteris)

that have tiny sori hidden beneath hood-shaped indusia.

Blunt-lobed woodsia sori. October 3, 2009. Jackson County, Ohio.

Blunt-lobed woodsia sori. October 3, 2009. Jackson County, Ohio.

One sandstone-cliff

specialist

moss, not very common, is easily identified when

characteristically bearing propaguliferous branchlets clustered uber-abundantly

in the

axils of the upper leaves. Because the clusters look like little

pom-poms, this is called "cheerleader

moss*," Brothera leana

(family Dichranaceae).

Brothera leana at Jackson County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

Brothera leana at Jackson County, Ohio. October 3, 2009.

*I just made that up. Nobody calls

it "cheerleader moss."