A Common Lichen in an Unusual Condition

November 20, 2018

Lemon lichen, Candellaria concolor, is a small brightly colored foliose lichen that is extremely common even n urban areas. The species reproduces by the production of powdery-granular soredia on the lobe margins, and rarely produces apothecia. Here on an ornamental elm tree on the Ohio State University campus the lemon lichen is abundant and, when examined closely, can be seen to be sparingly producing apothecia.

Lemon lichen, Candellaria concolor, with apothecia

Grimmia at Airplane Rock

November 18, 2018

Grimmia is a genus of dark (when dry) densely tufted rock-dwelling cushion mosses, that often (depending upon the species) have long white hair-points on the leaves. Identifying them to species can be quite trying, as the keys ask about features of sporophytes even though most often the plants don’t have sporophytes. This one, at “Airplane Rock” in Hocking County kinda matches Grimmia olneyi,but that would be rare and it’s hard to tell. Oh, well.

Grimmia on the rocks (with a twist of lemon?)

Milkweeds of Ohio

There are 13 species of milkweed (members of the genus Asclepias, within the family Apocynaceae, the dogbane family) in our State. Here they are presented in alphabetical order.

Asclepias amplexicaulis, clasping milkweed

Asclepias exaltata, poke milkweed

Asclepias hirtella, green milkweed

Asclepias incarnata, swamp milkweed

Asclepias purpurascens, purple milkweed

Asclepias quadrifolia, four-leaved milkweed

Asclepias sullivantii, Sullivant’s milkweed

Asclepias syriaca, common milkweed

Asclepias tuberosa, butterfly-weed, pleurisy-root

Asclepias variegata, white milkweed

Asclepias verticillata, whorled milkweed

Asclepias viridiflora, green-flowered milkweed

Asclepias viridis, spider milkweed, antelope-horn

Apparent Hybrids

Bio-blitz!

A rare butterfly on an uncommon plant

The Rock Run watershed in Scioto County is under threat from logging. To help demonstrate the importance of this area, a group of naturalist, myself included, spent the day June 3, 2017 exploring the area and tabulating as many species of living things as could be recognized. The results aren’t in yet. The Columbus Dispatch wrote a nice article about it that can be read HERE (link).

This may be a rare butterfly (there is uncertainty because apparently the band doesn’t look quite golden enough) Autochton cellus, golden-banded skipper foraging for nectar on an uncommon plant, Orbexilum pedunculatum, Sampon’s snakeroot, a legume formerly in the genus Psoralea. Although the skipper’s host plant (upon which its caterpillar feed) is a common species –hog-peanut, (Amphicarpa bracteata) –I was told that it’s recently been discovered that there are two co-occurring varieties, one common and one rare, of the plant which somehow differ in their chemistry and thus their appeal/utility to the skipper. The type the skipper feeds on the uncommon one.

Old limestone fence –a haven for lichens and mosses.

Griggs Reservoir, Columbus Ohio.

Flanking the west bank of the Scioto River in Columbus, Ohio, USA, there is a small park with a French-sounding name (Duranceau Park). The woodland remnants there are strongly influenced by the limestone bedrock and outcrops. Local limestone was quite some time ago used to construct a pretty little fence that marks the boundary of the park, separating it from the backyards of the adjoining residential properties.

The wall is a haven for mosses and lichens. One of them is a crustose lichen that is almost indistinguishable as to whether it actually is a lichen, rather than, say, a fossil or a mineral deposit. This is pitted stone lichen, Bagliettoa calciseda. (Earlier manuals referred to this as Verrucaria calcidseda.) The body if this lichen (its “thallus”) is within the stone (endolithic). The reproductive spore-bearing portion of this lichen –tiny flask shaped “perithecia” –are sunken into depressions in the limestone. Pitted stone lichen is widely distributed in northern and temperate regions wherever there is limestone.

Several of the other crustose lichens produce their spores in a more typical, obvious, and evident manner: a disk-shaped structure called an “apothecium.” Often the apothecia are all, or almost all, that can be seen of the lichen, as the thallus is thin and inconspicuous, or even endolithic. Some of the most colorful lichen apothecia are orange ones in the genus Caloplaca.” This beauty is “sidewalk firedot lichen,” Caloplaca feracissima.

An especially charming, although more subdued, lichen that also exists mainly as apothecia is one I like to call “buckeye lichen.” This is Sarcogyne regularis, the real common name of which is “frosted grain spored lichen.”:

“Sterile” crustose lichens, by which we do not mean germ-free, but rather lacking any spore-producing structures (i.e., apothecia or perithecia), are among the most challenging to identify. But here’s an easy one. It’s mealy firedot lichen, Caloplaca citrina. The thallus consists mostly of granular yellow-orange soredia (powdery granules consisting of algal cells and fungal hyphae, capable of dispersing and then developing into new lichens as a means of asexual reproduction).

OK, I know what you’re thinking…that picture shows a bunch of apothecia…what kind of sterile lichen has apothecia? Aha! You spied a different lichen…those gray and white disks are “mortar-rim lichen,” Lecanora dispersa. This species, quite the calciphile, is common even in cities, as the calcium in the concrete upon which it grows buffers the the effects of acidic air pollution.

Here’s another picture of Lecanora dispersa, at the edge of a fossil brachiopod.

The wall is home to some foliose lichens as well.

One of them is a strikingly white(ish) one called “frost lichen,” Physconia detersa.

Frost lichen is called that because the lobes are largely coated with a whitish “pruinia,” powdery frost-like deposits of some combination of crystals of pigment, crystals of calcium oxalate, and dead cortical cells. The photo below shows the frosty nature of the Physconia lobes, as well as some pretty severe competition with a colorful other foliose lichen, Xanthomendoza ulophylloides.

There are several similar genera of medium-sized foliose lichens distinguished, in part, by color. Phaeophysica is brown, with a black undersurface. The species shown here, I believe, is “powder-tipped shadow lichen,” Phaeophyscia adiastola.

Hey, what about the mosses? They’re there. (Aren’t I reassuring?) Cord glaze moss, Entodon seductrix is a shiny carpet moss (pleurocarp) with fingerlike branches.

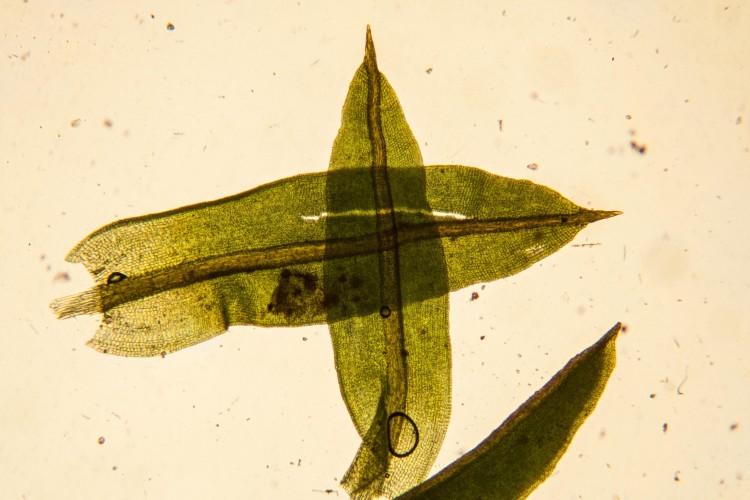

A moss that was at first tricky to identify because it looked so twisted when dry I thought it was tornado moss (Tortella) turned out, under close examination, instead to be bear claw moss, Barbula unguiculata.

Barbula leaf tips have a claw-like projecting tip.