Hooray…I actually went somewhere!

And oh, yeah…I have this old web site!!

The Middle of Somewhere, West Virginia

(Crum Bryological Foray, June 2-5, 2014)

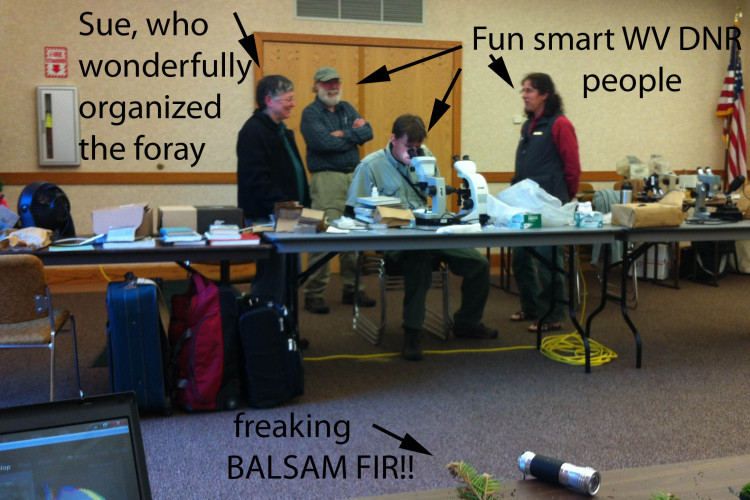

It sounded intriguing, and it was: an invitation to join a bunch of uber-friendly professional, amateur, and, such as myself, somewhere in-between (amafessional?) moss-heads in some of the most wild terrain this side of the asteroid belt. We were based at the lodge at Blackwater Falls State Park in Davis, West Virginia. It was the customary setup for a several-day bryological foray: field tripping in the daytime, followed by lovely evenings spent identifying our finds in a field lab set up in a conference room. There were lots of microscopes set up on folding tables, an arrangement sometimes known as “heaven.”

On Monday we visited a sugar maple-yellow birch-eastern hemlock-red spruce open woodland in Canaan Valley Resort State Park. Like all the places we visited, this park is in Tucker County. We hiked along the Blackwater River Trail. In true bryologist fashion, participants pressed their noses against tree and logs, looking not very weird at all.

A branch-crotch of a sugar maple tree was home to a seldom-collected moss, Anacamptodon splachnoides (family Campyliaceae). Anacamptodon is called the “knothole moss” for its tendency to occur on moist wood. In 2007, bryologists Donald Davis and Ronald Pursell published in Evansia the results of their concerted effort to locate this species, principally in Pennsylvania. They found that it indeed occurred most often in knotholes (11 out of 24 collections), followed by several instances on the quite similar substrate types of moist decayed hollows or crevices, and limb/trunk crotches. Three of their specimens were found atop a bracket fungus, Oxyporus populinus, also known as the “mossy maple polypore.” (In 1966, however, Aaron Sharp and Lewis Anderson collected Anacamptodon from a most unusual spot –a vertical moist rock face in the Great Smokey Mountains of Tennessee!)

Both the genus and specific epithets are in reference to the capsule. “Anacamptodon” refers to the bent back (when dry) peristome teeth, while “splachnoides” means resembling Splachnum, a nifty moss that grows exclusively on dung. The resemblance, a slight one, is in the peculiar manner in which the capsule is constricted below the mouth.

There is a beautiful marsh here.

The marsh is packed with mosses, including members of the genus Sphagnum, the principal genus in a class of mosses, the Sphagnopsida, situated near the base of the Bryophyta evolutionary tree alongside a few other small groups that either lack peristome teeth altogether or have peristomes of a markedly different construction than do the more typical mosses in the class Bryopsida. Peat mosses have several unique features, including the the occurrence of branches in tufted bundles (capitula) at the top of each stem.

Have you ever noticed that plants with a similar overall appearance seem to often occur side-by-side? Here we see “tree moss,” Climacium americanum (Climaciaceae) mixed with the peat moss, and seeming to be mimicking it.

Ohio has a fantastic flora, but it’s a wee bit lacking in the conifer department. The Buckeye State is certainly not the Spruce State or the Fir State, as neither Picea nor Abies occur naturally here. Hence it was a big thrill to see this beauty with leaves (needles) attached singly, and connected to the smooth branch with what look like little suction cups. Oooh, oooh, it’s balsam fir, Abies balsamea (family Pinaceae).

One of the fir trees was the substrate for common antler lichen, Pseudevernia consocians. Irwin Brodo, in Lichens of North America, mentions that a closely related European species of Pseudevernia is heavily collected for use in the perfume and cosmetic industry.

As if West Virginia knew the bryologists were coming, and we don’t even like vascular plants except as substrate for the good stuff, there were strikingly few flowers blooming this week. One of them was here in the marsh. It’s marsh blue violet, Viola cucullata (family Violaceae), one of the stemless violets. In this species the flowers are held strikingly high.

This region of West Virginia isn’t too far from the D.C. area. Vacation-wise, Tucker County is to the residents of Capital Region what Hocking County is to the people of central Ohio. One of the highlights of the foray was associating with friendly folks who know the area well, especially one named Joe, who lives in Washington and comes to Tucker County often enough to be a terrific interpretive guide. He took us to another wetland on the way back to the “lab” on Monday. This one was even fir-ier (more firry?), having the feel of an actual swamp (wooded wetland). I don’t remember where we were exactly.

Common haircap moss, Polytrichum commune (family Polytrichaceae) occurs in Ohio but, being a denizen mainly of wet acid open places, is quite scarce in most of the state, which is highly forested and/or has alkaline soils. It was thus a thrill to see dense hummocks and swards of this robust moss.

These sporophytes are not in the least bit reminiscent of people in any way. One is definitely not whispering in the other’s ear, nope!

On Tuesday we stayed close to home, in Blackwater Falls State Park. We hiked the Yellow Birch Trail/Allegheny Trail. This is a hemlock-red spruce wet forest (especially wet since it was raining a bit!) with scattered sugar maple and yellow birch trees with occasional sandstone outcrops and boulders.

As another instance of lookalike plants living together, the spruce saplings nicely matched the seedless vascular clubmoss, Lycopodium obscurum, growing right beneath them.

One of the best mosses we saw is a boreal species that’s quite rare in Ohio but more common here in The Mountain State. Occurring on humus and logs in coniferous forests, this is “knight’s plume moss,” Ptilium crista-castrensis (family Hypnaceae). Looking like miniature ostrich-ferns, the species can be told from the somewhat similar brocade (Hypnum) and fern (Thuidium) mosses by its more upright growth form and, in the case of Thuidium, its once-pinnate, rather than 2-3 pinnate branching pattern.

Through the microscope, the longitudinal folds (plications) of the plume moss leaves are evident.

Hooray for shiny pleurocarps that you can actually identify without experiencing brain damage! One such exceptional moss was abundant on the ground and tree bases; this is satin moss, Brotherella recurvans (family Sematophyllaceae). In the field, look for a flat braided appearance, especially shiny and golden.

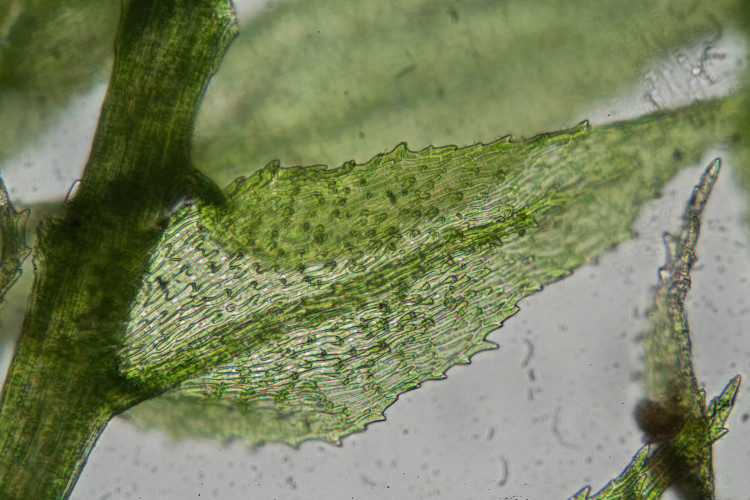

Through the microscope, look for a diagnostic trait of the Sematophyllaceae: large thin almost balloon-like alar cells (the cells at the outer corners of the leaf base).

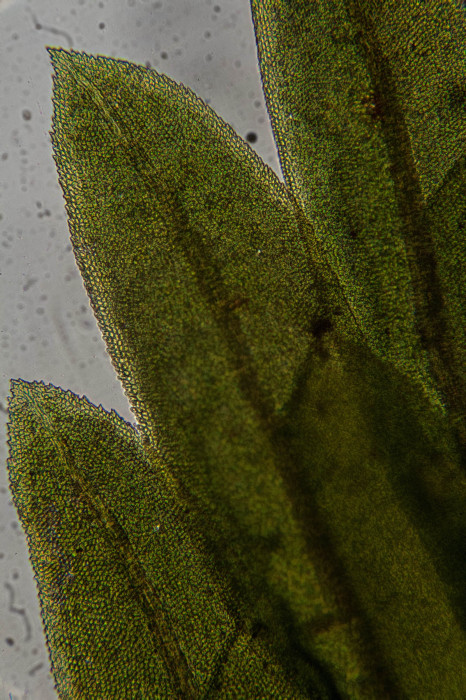

On thin soil over rocks, we found fan pocket moss, Fissidens dubius (family Fissidentaceae) to be amazingly abundant. Fissidens is flat, very flat. Nearly all mosses have leaves arranged in a tight spiral around the stem. Many mosses are somewhat flat (complanate) only because their stems and branches are compressed dorsiventrally, as if they were ironed or stepped on. However, a few moss genera have leaves that are actually arranged in two straight rows directly across from one another. Fissidens is such a two-ranked genus. (Thirteen species of pocket moss occur in Ohio, several of which are very common.)

Fissidens leaves have another peculiarity. Like the leaves of an iris plant, the base of each leaf that faces towards the stem apex is split, forming a pocket-like groove that clasps the lower base of the leaf just above it. The arrangement is suggestive of the way in which an equestrian’s legs clasp a horse, and so the plant is said to have leaves that are “equitant.” This species is distinguished in part by its leaves having a pale margin.

Lunchification happened at the Blackwater Falls State Park, Pendleton Point Picnic Shelter. This is an open area with scattered bigtooth aspen trees.

In spots the ground was covered with sand-loving Iceland lichen, Cetraria arenaria. Growth-form-wise, Iceland lichens straddle the border between fruticose (shrubby) and foliose (leafy), and may be best described as “upright foliose.”

On Wednesday we explored the Red Creek Trail at the Dolly Sods Wilderness portion of Monongahela National Forest. This is a humid mixed hardwood-hemlock forest with acidic rock outcrops and a few grottos with traces of calcareous rock.

One of the DNR people was kind enough to show me this insect he found on a leaf. It’s Desmoceros palliatius, the elderberry borer. According to a great new book that just arrived in the mail, Beetles of Eastern North America by Arthur V. Evans, adults of this species “emerge in spring and early summer and feed on flowers of wild and ornamental species of black elderberry (Sambucus nigra); larvae tunnel and feed in pithy stems. Mature larvae bore into roots and pupate at or just below soil surface. Life cycle takes one year in Deep South, up to three years further north.”

While everyone else was ranging far and/or wide, I pretty much camped out in this dark little grotto, and brightened things up excessively with my camera’s flash attachment.

This high point of the West Virginia trip was meeting the most magnificent thing that nature ever selected. Here in the grotto, it’s Flakea papillata, a foliose/squamulose lichen within a monotypic genus in the family Verrucariaceae that grows on moist sandstone deep in the dark recesses of such places, predominantly in tropical areas. Not the largest lichen ever; this photo was taken at 4x and then cropped a little after that, so it works out to about 5x. Blue whales are drooping their flukes a bit after finding out they are so far outclassed. Orchids are selling their pollinia on ebay and silverback gorillas are dyeing their hair. I’m considering getting a tattoo of this gorgeous thing.

Keeping Flakea company were a few mosses, including another shiny pleurocarp with the courtesy to be identifiable, through the microscope at least. This is grass-colored moss, Bryhnia graminicolor (family Brachytheciaceae).

What makes Bryhnia distinctive is its leaf cells. Long and narrow, they are papillose (extending upwards as pointed projections) at their ends, in the manner of warped up-curled floorboards you might find in a neglected an old house.

The calcareous element in this grotto is evidenced, perhaps, by the occurrence of a typically limestone-loving species, tall tornado moss, Tortella tortuosa (family Pottiaceae).

Dry Tortella (not to be confused with the Dry Tortugas, which are islands at the end of the Florida keys) is especially curled-crisped twisty tangled, winded all about itself and generally screwed up. This photo of dry Tortella tortuosa, while technically taken during the foray here in West Virginia, is actually of a clump of moss that one of the participants happened to bring along, gathered from an alvar in Lakeside, Ohio.

Our two common species of tornado moss –T. tortuosa and T. humilis — can be a bit difficult to distinguish from one another. This one has especially tortuously long-pointed leaves.

The family Orthotrichaceae includes mainly epiphytic, tufted pleurocarps which are so little-branched that they appear to be acrocarps. The two principal genera in our area are the bristle mosses (genus Orthotrichum) and the tuft mosses (genus Ulota). The trees of Tucker County, West Virginia are home to the most profuse growth imaginable of the aptly-named crispy tuft moss, Ulota crispa. Here’s a photograph of that curly-leaved beauty as seen in Ohio earlier in the year.

Rock tuft moss is a much less common Ulota with leaves that are not at all crisped. It has the general appearance of an Orthotrichum, but microscopic features of the leaf cells, and the emergent sporophyte with a hairy calyptra, taken together, reveal its true affinity.

Threadbare moss, Anomodon tristis, is a very thin pleurocarp that looks like tiny locks of green hair growing high on the bark of trees.

The name tristis means “sad” or “mournful.” Let’s call this “sad moss” from now on. That being said, it looks a lot less sad when it’s hydrated. Let’s call this “happy moss” from now on.

The final day of the foray was also spent at the Monongahela National Forest, mainly along a trail from Forest Service Road 75 along the boundary of Dolly Sods Wilderness to the confluence of Alder Run Bog and Fisher Spring Run Bog. This was a nutrient-poor sedge poor fen, that we accessed along a mixed hardwood-conifer forest trail.

The trail to the fen has open areas with nice mosses and lichens. One of these is pink earth lichen, Dibaeis baeomyces, a common and widespread eastern species that has an extensive white, crustose, ground-covering primary thallus. Extending above the ground are erect stalks capped by pinkish turban-shaped apothecia. Many members of the huge genus Cladonia are like this, except that the Cladonia primary thallus is composed of little squamules having a more foliose aspect.

Again it was a big thrill to see red spruce, as red spruce doesn’t occur in Ohio.

I mentioned to one of my fellow Ohio Moss and Lichen Association members that it was a shame that these moss photos, being taken in West Virginia, might not be suitable for the photo galleries on the OMLA web site. She suggested we could certainly put them on the site, because nobody would be able to tell they weren’t taken in Ohio. Here’s a photo of one of the starburst mosses, Atrichum oerstedianum, without a clue that it was taken in some state other than Ohio. Well, maybe one wee little clue.

The heath family (Ericaceae) apparently didn’t get the memo about this being a moss foray, and they insisted on hamming it up with their gaudy, almost obscene displays of sexuality. Here’s one called pinkster-flower, Rhododendron periclymenoides, clamoring for attention.

I had quite the spirited discussion with a wildflower enthusiast while I was photographing these two small cranberry (Vaccinium oxycoccus) blossoms. He insisted they had 4 petals which, despite the very obvious four-ness of the petals I insisted was incorrect because it’s in the heath family, which has five petals for sure, eh? It wasn’t until he showed me a wildflower guide that said they have 4 petals that I actually believed him.

Small cranberry, Vaccinium oxycoccus, is a delicate wetland shrub, the flowers of which have 4 swept-back petals.

The fen was magnificent! In addition to the sedges, Sphagnum and spruces, our terrific WV DNR guides pointed out that this is the southernmost natural occurrence of red pine, Pinus resinosa. Those are red pines in the foreground.

The spruces were adorned with some interesting lichens. I’m not completely sure of the identity of this one, but being a small gray foliose lichen with narrow lobes, covered with coarse isidia on all but the lobe tips, it appears to be salted starburst lichen, Imshaugia aleurites. (It it were on a pine trunk at Old Man’s Cave, I wouldn’t have any doubts.)

This pure brown twig-inhabiting lichen, abundantly beset with apothecia, is chestnut wrinkle lichen, Tuckermanopsis sepincola.

A wildflower that seemed to be everywhere we were in Tucker County WV this first week in June was bluets, Hedyotis caerulea (family Rubiaceae).

We carpooled to the Dolly Sods area. I was a passenger. I wanted to stay longer, so I figured I’d just drive this car back to the lodge, but then I remembered I didn’t have my wallet with me and I couldn’t drive without a license. Darn!

Well, it’s probably for the better. I’m not sure my driving skills would be quite up to negotiating the winding mountain road that led to our final lunch spot.

Our lunch spot was Bear Rocks along Forest Service Road 75. One of the DNR people mentioned that substantial numbers of golden eagles spend the winter here!

The rocks are great substrate for lichens, including this most conspicuous “plaited rock tripe,” Umbillicaria muehlenbergii. As reflected in the name, rock tripes are among the more edible of the lichens, although they are mostly just survival food. In Lichens of North America, Irwin Brodo mentions that the Nihitahawak people of Saskatchewan used pieces of U. muehlenbergii as an ingredient in a thick, stomach-soothing fish broth.

On the way back to the lodge we made a little side trip to some mystery location and saw this little calciphile on the ground, Weissia controversa (family Pottiaceae). I hope the golden eagles don’t see this next winter; its utter awesomeness might be too devastating a blow to their egos and make them lose confidence in their hunting abilities and become vegan or something, and try to subsist on Umbilicaria muehlenbergii.

Crucifers, Wee, Three.

West Side of Griggs Reservoir

Columbus, Ohio. April 7, 2011

On the entrance to this park with a French-sounding name just south of the Fishinger Rd. bridge over the Scioto River, there’s a grassy knoll with some inconspicuous alien annuals.

Lawn with some unobtrusive alien weeds. Duranceaux Park along the Scioto River. Franklin County, Ohio, April 7, 2011.

Lawn with some unobtrusive alien weeds. Duranceaux Park along the Scioto River. Franklin County, Ohio, April 7, 2011.

This trio of weedlets are principally self-pollinating annuals in the mustard family Brassicaceae, also called “Cruciferae” in reference to the suggestion of a cross (crucifix) shape formed by the 4 spreading petals. Members of the mustard family are thus often called “crucifers.” The shiest of the bunch is so-called “Whitlow-grass,” Erophila (formerly Draba) verna. It’s a good example of a winter annual, i.e., a plant that over-winters not as a seed, but as an immature plant with a little rosette of leaves, which bursts suddenly into flower and then fruit as soon as the weather is warm enough. It over-summers as a seed. The special mustard-family fruit of Whitlow-grass is the short and squat type called a “silicle.”

Erophila verna is a winter annual. April 7, 2011. Franklin County, Ohio.

Erophila verna is a winter annual. April 7, 2011. Franklin County, Ohio.

Here’s a crucifer with the long narrow special mustard fruit type called a “silique.” (Memory tip: a silique is sleek.) This is hairy bittercress, Cardamine hirsuta. (“Hirsute” means bearing long hais, which this species does, but the hairs are so sparse that you might miss them. Look at the leaf bases for the hairs.

Cardamine hirsuta is just barely hirsute, at leaf bases. April 7, 2011. Griggs Reservoir.

Cardamine hirsuta is just barely hirsute, at leaf bases. April 7, 2011. Griggs Reservoir.

The third mini-mustard is another silicle-producer. It’s one of the weeds whose common name references the coin-like appearance of the fruits: perfoliate pennycress, Thlaspi perfoliatum.

Perfoliate pennycress and hairy bittercress. April 7, 2011. Franklin County, Ohio.

Perfoliate pennycress and hairy bittercress. April 7, 2011. Franklin County, Ohio.

This is actually a rather uncommon species of Thlaspi, at least compared to the ubiquitous “field pennycress,” Thlaspi arvense, seen in profusion along roadsides and in waste places. (What is a “waste place” anyway?)

Perfoliate pennycress (left) and field pennycress (right, May 8, 2008, Marion, Ohio).

Perfoliate pennycress (left) and field pennycress (right, May 8, 2008, Marion, Ohio).

I’d like to give you my two cent’s worth about how to distinguish these two penny-cresses. The so-called “perfoliate” one has leaves clasping at the base (not actually perfoliate, however) whereas field pennycress has its leaves tapered to the base.

The other difference is in the fruits: larger and more deeply notched in the more common species.

Making sense of the tuppence. Left: the small, shallowly notched fruits of Thlaspi perfoliatum. Right: the big, deeply notched fruits of T. arvense.

A Tale of Three Dicranums

Waldo, Marion County, Ohio

April 6 and May 11, 2011.

It’s always fun to see different species in of the same genus growing side-by-side. At the Delaware (Ohio) Wildlife Area In Waldo (what is the location of that town)?) there’s a little meadow with numerous soil mounds covered with with mosses and other plants, that feature three types of “broom moss,” in the genus Dicranum (Dicranaceae).

Soil mound with broom moss times two. April 6, 2011. Waldo, Marion County, Ohio.

Soil mound with broom moss times two. April 6, 2011. Waldo, Marion County, Ohio.

The moss genus Dicranum consists of narrow leaved cushion mosses that often grow in dense cushions. Two especially robust ones are D. scoparium, which has especially narrow leaves that are upwardly curled at the margins, giving them a pointed-tubular appearance. Note also the dense velvety hairs along the stem (i.e., the stem is “tomentose”).

Dicranum scoparium has narrow leaves swept to one side. Waldo, Marion County, Ohio. April 6, 2011.

Dicranum scoparium has narrow leaves swept to one side. Waldo, Marion County, Ohio. April 6, 2011.

Meanwhile, our showiest Dicranum is D. polysetum. Its leaves are more broad and flat, and are disposed more regularly around the stem, which is even more tomentose. Note also how the leaves are wrinkled in an undulate fashion, making them glisten!

Dicranum polyetum leaves glisten. April 6, 2011. Waldo, Marion County, Ohio.

Dicranum polyetum leaves glisten. April 6, 2011. Waldo, Marion County, Ohio.

A re-visit to the meadow in May revealed another Dicanum. This is D. flagellare, a species that is easily recognized by its production of sword-like axillary “brood branches” that readily break off to develop into new plants, a means of asexual reproduction.

Dicranum flagellare produces abundant brood branches. May 11, 2011. Waldo, Marion County, Ohio.

Bartram’s Apple Moss

Symmes Creek in Wayne National Forest

April 2, 2011

Bartramia is a moss genus, and Bartramia is a bird genus. How can that be? Aren’t scientific names one-of-a-kind? Yes, mainly, but the system of botanical nomenclature, while it generally follows the same rules as the one for zoological nomenclature, is wholly separate from it, name-wise. Hence it is possible for two quite unrelated organisms to have the same name. I don’t know of any instances where both a genus and specific epithet are identical, but it’s fun to find plant/animal genus pairs. A favorite name-sameness is Bartramia. This beautiful moss is Bartramia pomiformis (apple moss).

Bartramia pomiformis is “apple moss.” April 2, 2011. Wayne national Forest. Gallia County, Ohio.

Bartramia pomiformis is “apple moss.” April 2, 2011. Wayne national Forest. Gallia County, Ohio.

The animal Bartramia is Batramia longicauda, the upland sandpiper. Here’s an old photograph taken by the “Father of American Ornithology, Alexander Wilson, of an upland sandpiper with a sprig of apple moss in its mouth, perhaps to be used as nesting material. What a coincidence!

Actually, even though the names are the same, in a sense they’re not exactly the same. Both are commemorative names commemorating Bartram, but they’re commemorating different Bartrams! Apple moss is named for the Philadelphia Quaker farmer who was one of the first great American botanists to systematically explore the eastern American colonies. The plover is named for his son William, who was more of a general purpose naturalist, quite famous for his wonderful written account of his travels to the southern colonies.

Lichenland!

Symmes Creek in Wayne National Forest

April 2, 2011

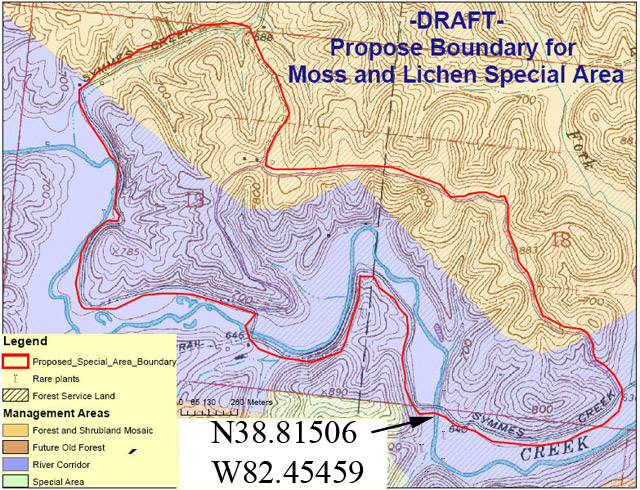

Super-friendly lichen expert Ray Showman held a lichen workshop a few months ago, of which Part Two was this awesome foray to an area of the Wayne National Forest in Gallia County that is especially rich in lichens and mosses. This place is under consideration for designation as a protected lichen and moss study area.

I’m trying to learn a few lichens. There are 233 species recorded in Ohio. Whenever I go out alone, I see the same few ones over and over again. This was a great chance to walk alongside someone with who had an eye for these things, and see what I’ve been missing.

Ray Showman demonstrates lichens. Symmes Creek, Gallia County, Ohio. April 2, 2011.

Ray Showman demonstrates lichens. Symmes Creek, Gallia County, Ohio. April 2, 2011.

What made this trip “work” for me was seeing unusual saxicolous (rock-inhabiting) members of genera that are familiar because they include common corticolous species.

The rock above is dominated by a large yellow-green foliose lichen called “rock greenshield lichen,” Flavoparmelia baltimorensis, a saxicolous counterpart of the very common F. caperata seen on trees everywhere.

In addition to its substrate, rock greenshield lichen can be differentiated from its common corticolous congener by its principal means of reproduction –asexual structures called “isidia.” Isidia are small cylindrical surface outgrowths which, anatomically, are extrusions of both the upper and middle tissue layers, plus the algal layer sandwiched by them. By contrast, the common greenshield lichen produces “soredia,” i.e., minute spherical bodies consiting of algae tangled up within fungal strands.

Isidia of rock greenshield lichen.

Isidia of rock greenshield lichen.

A closer examination of this boulder reveals an even more exceptional lichen, rock beard lichen, Usnea amblyoclada.

Usnea amblyoclada is “rock beard lichen.”

Usnea amblyoclada is “rock beard lichen.”

The lichen genus Usnea is easily recognized by its pendant or filamentous, shrubby growth form. Species identification can be challenging even for experts. This one, U. amblyoclada tends to grow in bushy tufts from a single point, and occurs only on rocks. (All other Ohio species of Usnea occur exclusively, or nearly so, on trees or wood). The species ranges widely across much of the southern U.S. This station is near the northern limit of its range.

This large gray foliose lichen, Parmotrema xanthinum, is another rock-climbing counterpart to a more familiar tree-hugger (the so-called “ruffle lichen,” P. hypotropum).

Parmotrema xanthinum on the rocks (with a twist of lemon?)

Parmotrema xanthinum on the rocks (with a twist of lemon?)

An interesting lichen growth form, additional to the familiar three –crustose, foliose, and fruticose –is the one called “umbillicate,” Umbillicate lichens are large, flat, and centally attached to the substrate. This particular species, Lasallia papulosa is quite distinctively warty-surface, and thus called “toadskin lichen.”

A super-nifty few lichens stand apart from the rest in that their photosynthetic component (the “photobiont”), instead of consisting of green algae, instead are blue-green bacteria! Some of these lichens tend to have a striking gelatinous texture. Here we see two of them side-by-side: members of the genera Collema and Leptogium. The Leptogium, seen on the left in the picture below, has a slightly juniper-like blue-green cast, compared with the more deeply-green Collema.

Gelatinous lichens: (left) Leptogium and (right) Collema.

Gelatinous lichens: (left) Leptogium and (right) Collema.

Here’s a closer view of the Collema.

Collema is a gelatinous lichen with a cyanobacterial photobiont.

Collema is a gelatinous lichen with a cyanobacterial photobiont.